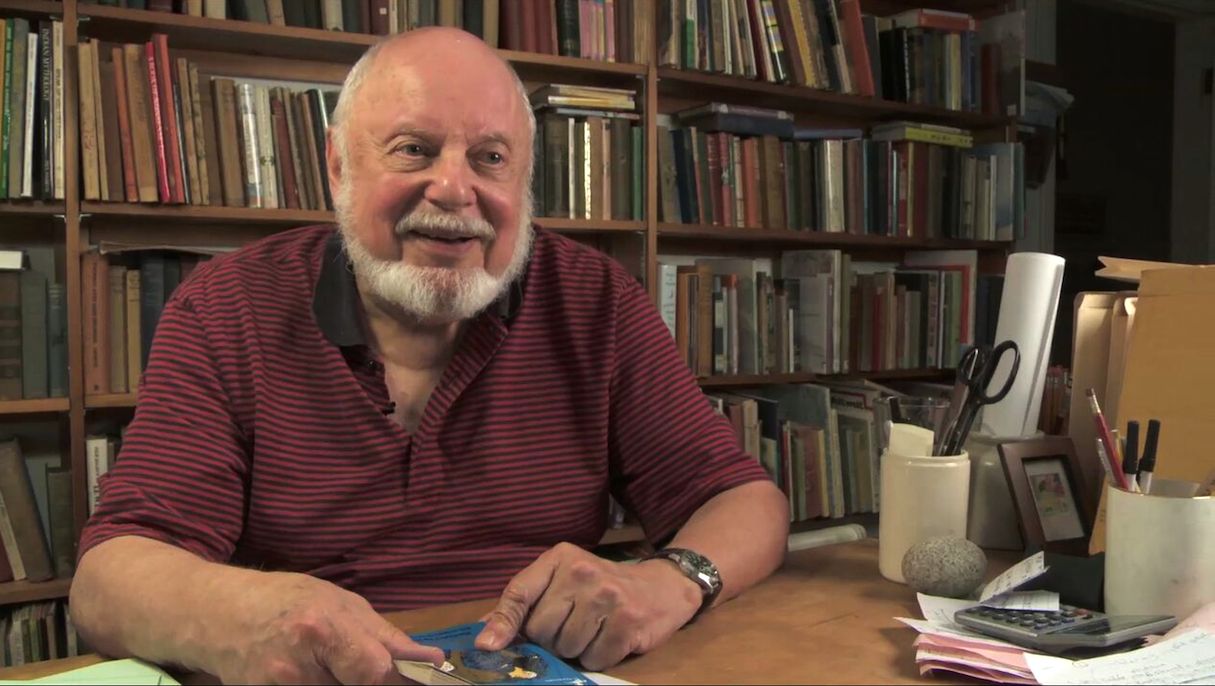

A certain kind of ex-child will be ecstatic to read that Norton Juster will come to Washington on July 12 for a screening of a new documentary on his famous children’s book The Phantom Tollbooth.

The Phantom Tollbooth: Beyond Expectations tells the story of how the Phantom Tollbooth came to be and delves into the relationship between Juster and his longtime friend, Jules Feiffer–the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist who illustrated the book. (It also includes testimony from four students at Georgetown Day School.) Here’s a sneak peek of what you can expect to hear from Juster on Sunday at the National Museum of Natural History.

Take us back to 1960, when you first started working on the Phantom Tollbooth. What inspired you to start writing?

I had just gotten out of the Navy, and I really didn’t know what I wanted to do. I got started on this book on urban design and planning, and I realized I wasn’t ready yet for it. In order to get my mind off it for a while, I started a little story. I didn’t know where I was going with it, and that turned into the Phantom Tollbooth. Quite often I end up doing something because I’m trying to avoid doing something else I’m supposed to be doing. That may sound like a screwy motivation, but it sometimes works.

How was the book received when it was first published?

When the book was first coming out, the people at Random House sent it out to a number of people to get reactions–school teachers, librarians, critics, other writers, things like that. And all their responses came back in a very similar way: No. 1:This is not a children’s book. No. 2: The vocabulary is much too difficult. [Kids] are never gonna understand it or be interested in it. No. 3: the subject of it is something they’re not going to understand, and number four, the word play and the punning will be way beyond them. They ended up saying, “Besides, fantasy is bad for children, because it disorients them.” You can imagine my reaction!

What something means is what it means to that person at that time in their life. That was very different than what was happening in children’s books at that time. That’s why there was so much doubt about it. There are no words that are too difficult. There are only words that you haven’t seen before. As soon as you do, you know something about them, and you use them.

They were all luckily dead wrong, because [the book is] now on its 54th year, and it’s still going strong.

Why do you think it’s been so successful?

It’s very simple. Kids–no matter how the world changes, how the hardware changes, what kind of machines we’re using, whether you have a smartphone, or a this, or a that–they still think about and worry about the same issues, are afraid of the same things, don’t understand the same things, are uneasy or insecure about the same things. That part doesn’t change. All the stuff around it may change, but kids still have to grow up, and they are very much the same at certain ages.

One of the things we get constantly about this book–which gives me great satisfaction–is that [people] talk about how it has changed their lives and changed how they think about things. That’s the name of the game in my estimation. That’s what you want.

You’ve written a long list of books since Tollbooth. What kinds of books did you read as a kid, and how did they influence your writing as an adult?

I did a lot of reading, because I was very isolated, very introverted as a kid. I would read anything–from cereal boxes to however difficult, or supposedly difficult, a book was. I’d go to the library all the time and be thrown out of the adult section because I shouldn’t have been in there.

One of the things I read was from my parents’ shelf of long Russian novels in English translations. I started to read some of those Russian novels, and some of them were 1,200 to 1,400 pages–endless. I would read them through and really not understand what I was reading, but what I loved was the sound of the language, the words, the music of the words. This has influenced me enormously.

To this day, I read a tremendous amount of poetry, and I would guess conservatively that at least 80 percent or more of what I read in poetry, I do not literally understand. I read it because it’s almost a melody for me–the way you use words to create not only pictures, but a mood and the way things feel. That’s the way I think when I write. Whatever I write has to have that sense of pace and music and rhythm. Kids–that’s how they get passed difficulties. That’s how I got passed the difficulties of the Russian novels.

A big part of the documentary focuses on your relationship with Jules Feiffer. How did you two meet?

Jules and I met in a very strange way. My last stationing, when I was in the Navy in the late ’50s, was in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. They gave me two choices: I could either live at the Navy Yard, or they’d give me a living allowance, and I could get a little place to live off-base. That was a no problem for me. I wanted to live off-base.

So I walked over to Brooklyn Heights, and I found a basement apartment, which was kind of grubby, and guess what, Jules lived in a small apartment on the second floor. That’s how we met and became very friendly. He was very funny and very bright and very involved with all kinds of things political and social. Those were all my interests, and we got to know each other and kid each other and become part of each other’s lives.

He claims we met when we were both taking out the garbage. I claim we met when I was taking out the garbage, and he was looking for something to eat.

The Phantom Tollbooth: A Celebration of a Classic with Author Norton Juster and Bill Harley, hosted by Smithsonian Associates, takes place on July 12 from 3 to 5 PM at the National Museum of Natural History. $10 to $25.