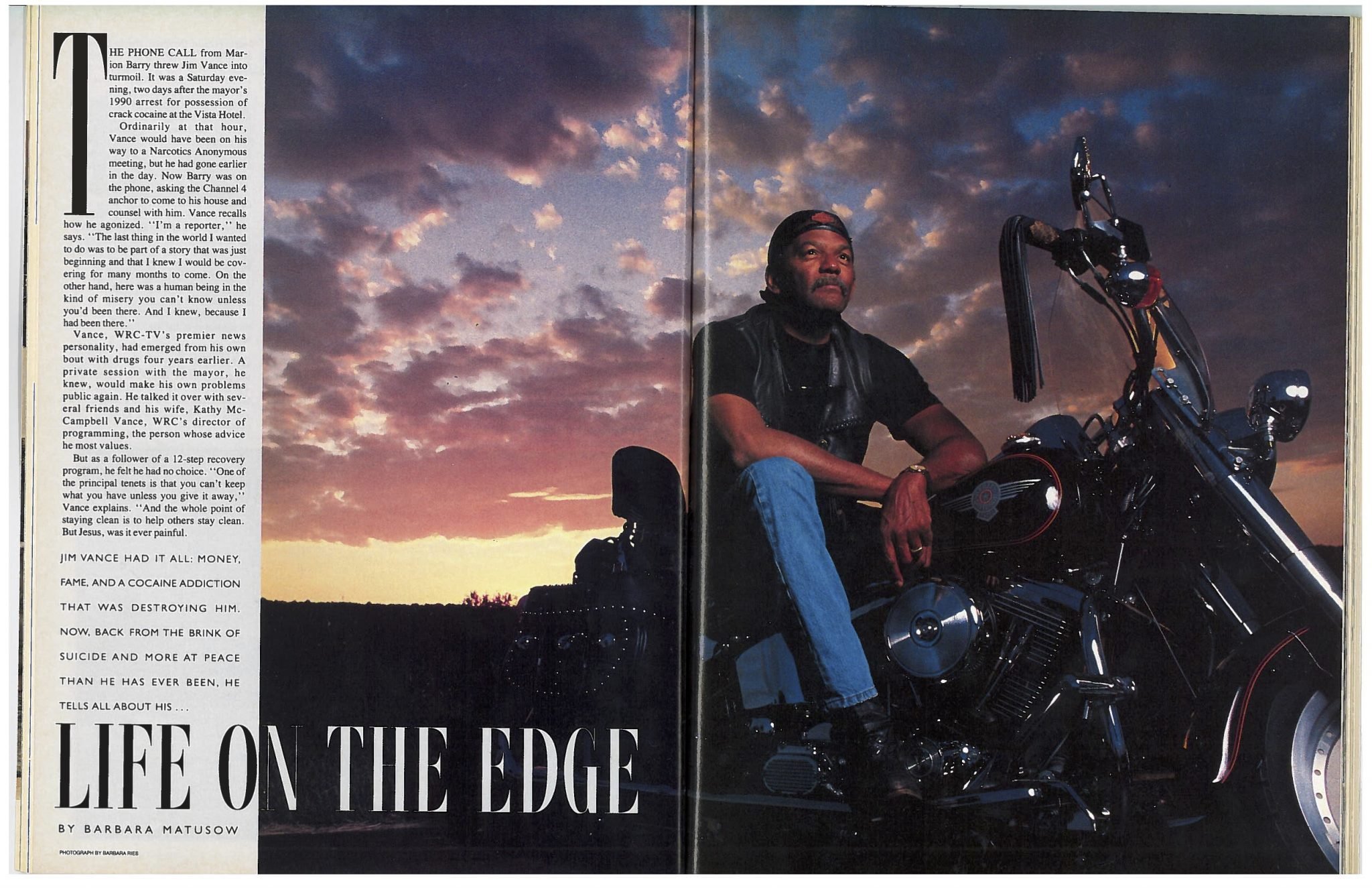

The phone call from Marion Barry threw Jim Vance into turmoil. It was a Saturday evening, two days after the mayor’s 1990 arrest for possession of crack cocaine at the Vista Hotel.

Ordinarily at that hour, Vance would have been on his way to a Narcotics Anonymous meeting, but he had gone earlier in the day. Now Barry was on the phone. asking the Channel 4 anchor to come to his house and counsel with him. Vance recalls how he agonized. “I’m a reporter,” he says. “The last thing in the world I wanted to do was to be part of a story that was just beginning and that I knew I would be covering for many months to come. On the other hand, here was a human being in the kind of misery you can’t know unless you’d been there. And I knew, because I had been there.”

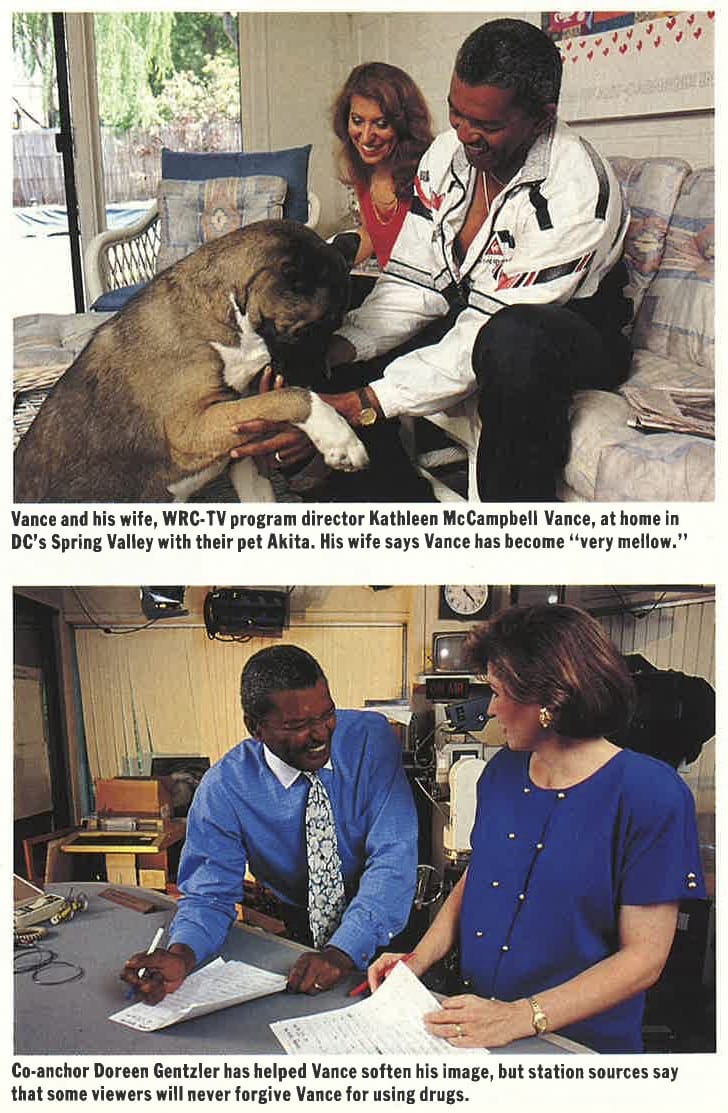

Vance, WRC-TV’s premier news personality, had emerged from his own bout with drugs four years earlier. A private session with the mayor, he knew, would make his own problems public again. He talked it over with several friends and his wife, Kathy McCampbell Vance, WRC’s director of programming, the person whose advice he most values.

But as a follower of a 12-step recovery program, he felt he had no choice. “One of the principal tenets is that you can’t keep what you have unless you give it away,” Vance explains. “And the whole point of staying clean is to help others stay clean. But Jesus, was it ever painful.

“I cried when I first heard that Marion was arrested. One, because I knew what he must be suffering. And I knew it was only by the grace of God that I had not been humiliated in that way. On another level, as a black man, I was angry, embarrassed, ashamed, and hurt—ashamed because of what whites would think, and angry because I felt he was giving his enemies such a cheap shot.”

Contrary to widespread innuendo, Vance and Barry were never pals or fellow drug-users. True, they both frequented the smoky, late-night bars on Capitol Hill in the early ’80s, places like the Gandy Dancer where people played backgammon till dawn and sometimes did cocaine. But Vance says he didn’t run into the DC mayor. “I had never in my life partied or hung out with Barry. I had contact with him as a journalist, but there never was a history of social interaction or drug use or anything else like that. When Barry called that night, I had to ask somebody where his house was.”

On the way out the Southeast-Southwest Freeway, Vance was dreading the encounter, unable to think of what to say or do that might be helpful. “I remember praying out loud in the car. I kept repeating it, almost like a mantra— ‘Lord, make me a vessel. Make me a vessel.’

“Then I got there, and Jesus, they had all those lights on, and trucks and reporters coming out the ying yang. They were just like roaches, skittering every time the light went on in the kitchen. And I thought, ‘Lord, give me strength.’

“As it turned out, all Marion really wanted was to ask me about my experienêe in treatment, what the best facilities were, and what I thought he should consider doing. God, if only I had known that on the way over. The rest of it was sharing the pain.”

NINE YEARS AGO, Jim Vance was holding a shotgun to his mouth at Great Falls. Today, he says, he’s happier and more at peace with himself than ever before.

“The pain and agony I suffered from using drugs was so terrible I preferred death to life,” he says. “I don’t want to get schmaltzy about it, but as a consequence of not surrendering to those dark temptations, the sun that I see every day is much brighter than I’ve ever seen it before. Everything in my life is better. It’s something I never, ever want to do again. But it’s also something I never, ever intend to forget.”

At age 52, Vance still has his driving, restless energy. But now he has a lot to be happy about. In May, he celebrated his 25th anniversary with WRC, prompting an outpouring of tributes. He earns a ton of money. He’s married to a woman he adores. His children are grown and doing well. And his stature with the public and his colleagues is at an all-time high.

“I don’t look to anyone in this world for approval except Jim Vance,” says Channel 4 sportscaster George Michael. “To have come from where he comes from, and undergone what he has undergone, and to emerge with his pride and dignity intact. . . . Apart from my wife and my daughters, there is no one I love more.”

Michael is one of the few people at WRC who can claim to know Vance intimately. Jim has a smile and a howdy for everyone, and people feel free to drop by his office to schmooze, smoke, or bemoan the state of local news. But Vance invites only so much familiarity. “He’s really more of an introvert,” says Kathy McCampbell. “He doesn’t hang out with buddies.”

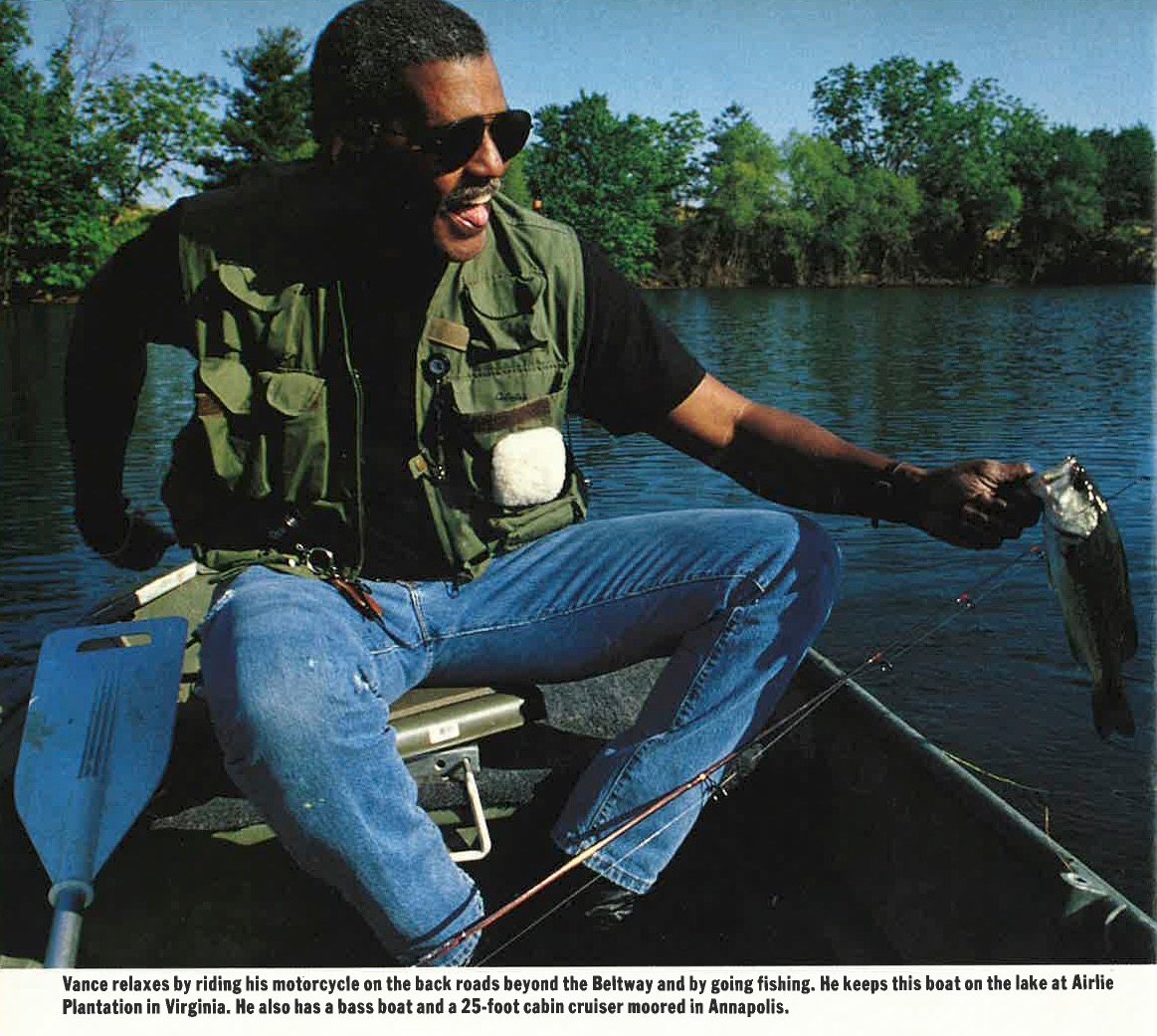

Many a time, his wife says, they spend hours together without exchanging a word while Vance tinkers with something like his beloved fishing gear. “He can sit there with his big, three-tiered tackle box. which holds his wigglers, rattlers, and a hundred other lures of every shape, size, and color, and he’ll take them all out and spend hours rearranging that box.”

In self-defense, McCampbell recently took up the piano and sketching. “I went out and bought a book on drawing, some pastels, and a box that looks like his tackle box,” she says. “So now, when we go fishing, I sit and arrange my pastels.”

The pain and agony I suffered from using drugs was so terrible I preferred death to life

JIM, KATHY, AND BRENDON, her son from a previous marriage, live in DC’s Spring Valley, in a brick split-level house whose most notable feature is the bass boat parked outside. Inside, the place is cheery and comfortable but plainly furnished. There’s no rug on the living-room floor, and the art on the walls tends towards framed posters. Their most conspicuous luxuries are Vance’s ’91 Mercedes convertible, his top-of-the-line Harley Davidson “Fatboy” motorcycle, and the kidney- shaped pool in the back yard.

When I show up at the door for our first interview, Vance is not thrilled to see me. We have been friends on a professional level for 20 years, from the time I produced the nightly newscasts at WRC, but for the past five years he has refused a half-dozen of my requests for an interview. He agreed this time only after learning that a profile of him was under way with or without his cooperation.

Vance is distant as he shows me into the kitchen, and we stand there silently as he pours two mugs of coffee. I’m surprised to see that he is nervous. I joke that I felt like Dr. Death on my way over that morning, with my tape recorder and the other tools of the trade in my briefcase. This makes him laugh, and we both relax.

In the living room, Vance sprawls on the white leather sectional sofa, chain-smoking Camels. Dressed in jeans, a nubby gray sweater, and brown cowboy boots, he is even bigger and better-looking than he appears on TV. True, there’s more salt than pepper in his mustache these days, and he has gotten a little jowly. But one woman who enjoys watching him while he works out at his health club reports that he’s still in terrific shape.

Having decided to cooperate with the profile, Vance, an all-or-nothing kind of guy, holds nothing back. His marriages, his battle with drugs, his racial hang-ups, his joys, sorrows, and fears—he puts everything on the table. After having spent five years in therapy, he says, he finds it easier to open up.

JIM VANCE MUST have been a tough nut for his therapist to crack. Family members recall him as a moody, quiet child who played mostly by himself.

“He never wanted anybody to see what he was doing,” recalls his favorite aunt, Vivien Vance Cherry, who lived on the same street in Ardmore, Pennslyvania, where Vance spent most of his first 17 years. “Whether he was reading a book or fixing his bike, he did not want any interference. None. And he’ll kill me for saying this, but he was a crybaby. He cried about everything. I guess he was about 3 or 4 before he got hold of himself.”

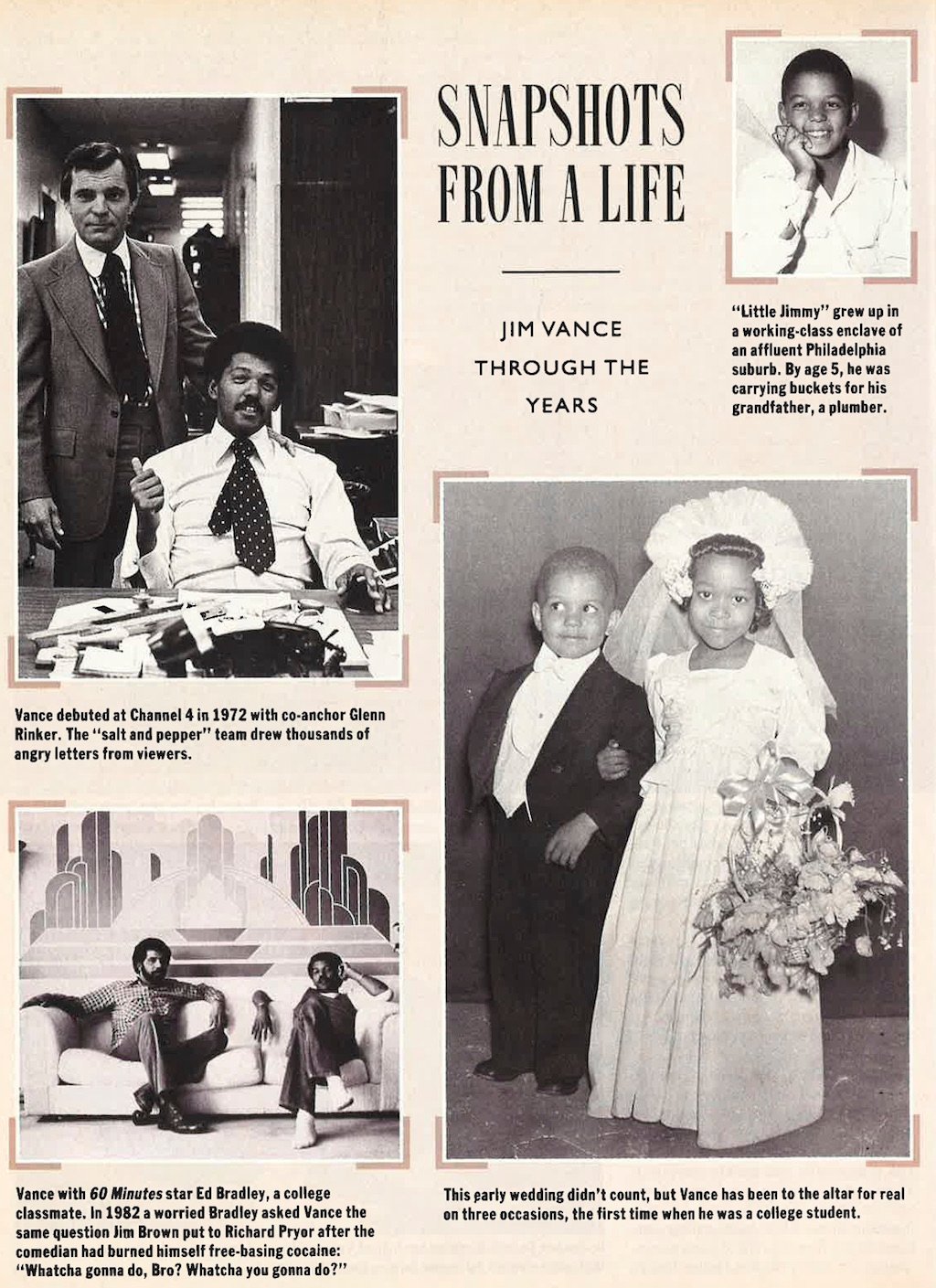

Little Jimmy, as everyone called him, was raised mostly by his grandparents and his aunts and uncles. His father, who came back from World War II with a bad drinking problem, died of cirrhosis of the liver when Jim was 9. Shortly afterwards, his mother moved back to Philadelphia. Jim didn’t seem to mind at the time, because his grandfather was his main man.

“Pop” was a plumber who raised 15 children. Quiet and strong, he could strap a bathtub on his back and carry it up a flight of steps when he was 75.

All the men in the family worked in the family plumbing business, James H. Vance & Sons. So did Little Jimmy— James H. Vance III. At age 5, he cleaned copper fittings and carried buckets for 25 cents a week.

“The best, most precious moments I spent were sitting with my grandfather on the front porch, rocking,” Vance recalls. “He didn’t talk much, but I never felt closer to another human being. When I was with him, I had the feeling of being loved and cherished and protected. ”

The Vances lived in a working-class enclave in Ardmore, a suburb on Philadelphia’s Main Line. They were a hard-working, self-reliant clan, looked up to by their neighbors. Twelve of Jim’s aunts and uncles graduated from Lower Merion High School, one of the best public schools in the country. Six went to college, including an aunt who became the first black woman to graduate from Bryn Mawr.

Jim, the only male grandchild for some time, was held to exacting standards by his uncles-a proud, hard, macho lot. “I was expected to stand out. C’s just wouldn’t do,” Vance says.

“In sports, I was expected to be a starter on all the teams I played on. “I used to walk through the house and somebody would inevitably do this” —he gets up to illustrate a swift slapping motion starting at the midriff and ending under the chin— “meaning, ‘Straighten up. Hold your head up. Stand up. Be a man,’ I remember all of them telling me, ‘Never let ’em see you cry. Never show weakness.’”

When Vance was 16, he injured the cartilage in his ankle playing ball. One of the uncles took him to the hospital to get the cast off, and when they got home, Jim took hold of the railing and began dragging his bad leg up the steps. “My uncle, who’s behind me, says, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ I said, ‘I can’t bend my knee.’ He said, ‘Oh, yes you can.’ ‘No,’I said, ‘I can’t. It’s still hurting.’ He took his knee and slammed it into the back of mine. And he looked at me like, ‘Don’t you dare think about crying.’ So I didn’t. What I did was to turn my feelings into rage and hatred. I wanted to kill that son of a bitch,” he says, able to laugh at the incident now. “But I did bend my knee and walk up those steps.”

His aunts were strict, too. “Our kids had to speak proper English,” says Vivien Cherry. “Aunt Rett was always chewing him out for not speaking correctly. But I always took his side, right or wrong. I felt he had to have somebody in his corner.”

Aunt Vivie didn’t get mad even when she lent him her car and he smashed it up. “That rascal was playing chicken on Lancaster Pike and hit a fire hydrant,” she says. “I figured, what’s the use of bawling him out? He didn’t get hurt, which is the main thing.” But she did ask him how he planned to pay her back.

VANCE WASN’T AWARE of racial discrimination in his early years. Until the late 1940s, his neighborhood was mostly white, and he played with kids who had names like Bongiovani and O’Boyle. Even on auto trips to visit relatives in North Carolina, he never wondered why family members sometimes had to make rest stops by the side of the road.

“I could read when I was 4, and when we found a gas station, I’d see these signs that said COLORED REST ROOM and I’d think, ‘Hey, we got our own. Ain’t that neat?'”

By the age of 8, he began to realize that he was different, and somewhere along the line, he developed a vague sense of having something to prove, of never really fitting in. The feeling intensified at Lower Merion High, where there were fewer than 20 blacks in his class, and he was the only one on the academic track.

“Only one white kid ever invited me to his house the whole time I was in junior high and high school, ” Vance says. “But I played a lot of ball and sang a lot, so I felt comfortable around my white peers. My teachers were another story. I got the distinct feeling that most of them—my math teacher, my physics teacher, my history teacher—wished I weren’t there.”

Once, his physics teacher blew on a dog whistle and asked if anyone could hear it. “I was the only person who raised my hand,” Vance recalls, “because I swear to God I could hear that thing. And he looked at me with such scorn and disdain, I’ll never forget it. He made some remark about my kinship to lower animal forms and how they had higher auditory senses. And it just destroyed me.”

Partly because he disliked his teachers and partly because it wasn’t cool to be too smart, he did just enough work to get by. Except for English. “My English teacher, Mrs. Fowler, whose memory I will cherish for all of my life, would not accept anything less than what clearly was my best effort. I really did love her. For one thing, she was nice to me. That was the one class I could go to where I wouldn’t feel like maybe I don’t belong here.”

The most overt discrimination he encountered was at the hands of other blacks. A group of aristocratic, light-skinned blacks in a neighboring community had built their own swimming pool—the Nile Swim Club—and they were selective about who could join. One day a friend took Vance there, and although he was allowed to swim, he was conscious of the raised eyebrows and disapproving looks. After he joined, he felt snubbed.

“I was too dark for the Nile Swim Club,” he says. “They treated me like shit. I was so busted, so hurt by that.” The experience left him with a chip on his shoulder toward the color-conscious black bourgeoisie with its emphasis on proper speech and decorum.

THE BEST PARTS of Vance’s adolescence were sports—he ran track and played on the football and basketball teams—and music. He played bass guitar, sax, flute, and sang with a doo-wop group, the Joy-tones, that was in demand at parties. Often the group practiced until 2 or 3 a.m. for the sheer joy of singing. He also started sneaking down to the jazz clubs in Philadelphia, sipping Cokes, and listening to Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Lee Morgan.

At the same time, he began indulging his attraction to danger. He’d stand as close as he could get to speeding trains. And he began to run with a gang. They carried blackjacks and zip guns—Jim made them them from materials filched from his uncles—and fought in gang wars.

Vance got arrested a couple of times and was lucky he didn’t end up in jail when he punched a policeman who had waded into the middle of a fight and hit Vance in the nose with a two-foot-long flashlight. Instinctively, Vance swung back, knocking him out. “When I saw him lying there on ground, I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’ve killed a cop.”‘

His friends hustled him away, but later that night he heard a description of himself being broadcast on the radio. The episode frightened him enough that he quit the gang.

His family had begun to despair at his wildness. “The only one who always took up for me was Aunt Vivie,” he says. “The rest of them thought I was crazy or dangerous. I guess she saw something in me the others didn’t, but I don’t know how she knew. I thought I was dangerous. I wanted to be dangerous.”

COLLEGE WAS A TURNING POINT in Vance’s life, even though he didn’t want to go. He wanted to be a plumber, like his father and his grandfather. He liked doing things with his hands, seeing the result of his labor.

But the family sat him down at the big round dining room table where all matters of importance were addressed. Blacks were not allowed in the plumbers’ union in those days, which kept them out of construction jobs. Without a college degree, his family told him, he never would be more than a jobber, fixing other people’s leaky faucets. Teachers could always get a job. So Vance enrolled in Cheyney State, a black teachers college outside Philadelphia.

For the first time, he would have an inkling of what it felt like to belong.

“I was thrilled to be going to an all-black college,” he says. “Cheyney was the first experience in my life in a predominantly black environment, where I felt comfortable, safe, and nurtured. All around me, I felt there were adults who wanted to be helpful to me. At a school like that, if you were going to fail, you were going to have to work at it.”

A big, quiet kid who drove a broken-down ’49 Cadillac, Vance couldn’t afford to live on campus or buy sharp clothes, but everyone knew he was there.

“He had this air about him,” says Ted “Bucky” Nickens, a classmate who is now a deputy chief of the civil-rights division at the Justice Department. “I remember the first time I saw him. He was this tall, lanky, thin-legged guy wearing a toggle coat and a brown fedora and smoking a pipe, which I guess was his idea of what a college guy was supposed to look like. He carried himself like ‘I am The Man,’ and rightly so. The women loved him.”

For the first time in his life, Vance made real friends, including Ed Bradley, now a star on CBS’s 60 Minutes. Bradley was nicknamed “Moon” in those days because his head was so big. “We had a hard time finding a football helmet big enough to fit him,” laughs Vance. “Bradley and Bucky were city kids, and they used to laugh at me for being ‘country.’ But somehow, when they Jonesed on me, it didn’t hurt my feelings. They accepted me. That was so…so nice.”

In his sophomore year, Vance got married. Four months later, his first child, Dawn, was born. “Back then, if a girl got pregnant, you married her,” he says. “That’s how it was. But God, I loved that baby.” He and Margo, his wife, moved into his mother’s apartment in West Philadelphia. Margo dropped out of school to work while Vance continued to go to Cheyney. With no money for babysitters, he used to take Dawn to school with him.

“I was a baby with a baby,” he says. “Here I was, a sophomore in college with a wife, a child, and a job, and playing ball. I would pack Dawn up at 6:30 in the morning and take a box of diapers and pins and bottles and stuff, and I’d take that kid to class. And man, was it, the best thing I could have done. Oh, I had girls around me like flies around honey. I was a big man on campus. They all wanted to take care of my baby.”

The marriage lasted 10 months. Margo pretty much dropped out of Vance’s life, but he continued to take care of Dawn a lot. When she was 13, she went to live with him permanently. Ed Bradley, who adored baby Dawn, often took her for the day, driving her around in his convertible. Sometimes, he and Vance would dream about their futures.

“I remember one Saturday we were playing basketball on the playground all day,” Vance recalls. “Afterwards, we were eating water-ice and pretzels with mustard, fantasizing about the day we would make $15,000. That was our goal, $300 a week. We figured it couldn’t get much better than that.”

AFTER GRADUATION, Vance got married again, this time to Barbara Schmidt, a fellow Cheyney student and the daughter of a prominent Philadelphia attorney. He began teaching English at Strawberry Mansion Junior High School.

Never lazy, Vance went into overdrive. His father-in-law staked him to a gas station, which he opened and closed every day. On the side, he was fixing up old cars for resale. At the same time he got his first taste of the news business, doing radio newscasts on weekends for a popular deejay known as the “Mighty Burner.”

His real love was the Philadelphia Independent, a now-defunct black newspaper acquired by his father-in-law’s partner. “I was the circulation manager, reporter, paste-up guy, and everything else you can think of. On Thursdays I would stay up all night, pasting up the paper and taking the pages to Bordentown, New Jersey, about 35 miles away. I had to take cash with me because we didn’t have any credit. When the [printing] run was done, I would take the papers back to South Philadelphia, then go open up the gas station at 6 o’clock and wait for the day guy to come on.”

”He just couldn’t let it go,” recalls Barbara Vance, who lives in Washington and runs a speakers bureau. “He might get a few hours of sleep, teach school, then go to work on the newspaper. Luckily, he never needed much sleep.”

VANCE THRIVED ON THE PACE, but it wasn’t enough. He always needed edge in his life. This time he found it by running around with a bunch of Philadelphia-style gangsters known as wreck-chasers.

“They had police radios in their cars, and when they heard an accident, they would haul ass, trying to get there before any other wreck-chaser. They would go riding up the sidewalks, down one-way streets the wrong way at 110 miles an hour, never stopping for red lights—I mean it was exciting to ride with those guys.”

The wreck-chasers, who wore fine clothes and drove fancy cars, would present themselves to the accident victims before the police or anyone else could get there. “These guys were so glib and so articulate and such hustlers,” Vance says. “The point was to get you to take your car to their auto mechanic, who they got a cut from, to their auto body shop, to their doctor, to their lawyer, all of whom they got a cut from. Anything you needed, they could fix up for you. They were so cool.”

Ultimately, the wreck-chasers would introduce Vance to something far more dangerous than car chases. ”I was a ’50s kid,” he says. “I didn’t get drunk for the first time until I was 16 years old. They made us football rookies sit on a stool and drink a Welch’s jelly glass full of vodka. I drank it and fell off, and it was a long time before I had a drink again. I knew even less about drugs. When I finally discovered marijuana, I really didn’t like it. But I did it because I wanted to fit in. I wanted to be cool like everybody else.”

One night in 1966, when he was 24, a couple of wreck-chasers took him to a house in West Philadelphia to see a friend of theirs—a convicted murderer who had been let out of prison that day. They were standing around, shooting the breeze, when somebody brought out a $100 bill with cocaine in it. “There were seven or eight guys, just standing in a kind of loose circle,” Vance recalls. “I didn’t know anybody except these two guys I went in with, and I was scared to death. I mean there were two guns on the table. I had never been nowhere with guns on the table. And I was watching those guys as they passed this thing around, so that I could do what they did when it got to me. And I did, and I hated it.”

Vance says he didn’t do cocaine again for two or three years. By then it was the late ’60s, and drugs were out of the closet. “I did what everybody did in the ’60s. I tried every narcotic substance on the face of the earth. But 99.9 percent of them I only did once, because I really didn’t like them.

“As a consequence, I developed the total conviction that there wasn’t any way in the world that I could ever be addicted to any chemical substance. Because I had picked them all up and put them all down. And I was in total control.”

IN 1968, someone suggested to Vance that he apply for a job in television. The cities were in flames, and TV stations were scrambling to put black faces in front of the camera.

Vance remembers that his reporting audition, “at this little rinky-dink station in Philly, was a complete abortion,” but he got the job. A year later, he had five offers from bigger and better stations, including WRC. He and Barbara packed up their ’67 Camaro and headed for DC. Not long afterwards, Amani, Vance’s second daughter, was born.

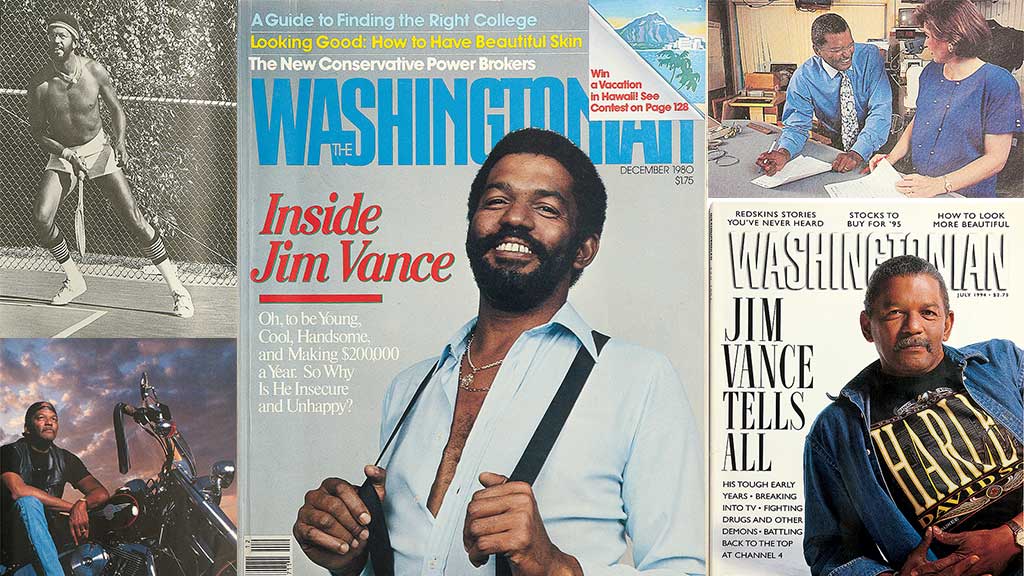

Like most people in TV in those days, Vance was thrown into the field with very little training. But over the next 10 years, he experienced too much of everything else: too much money, too much adulation, too many women, too much fear, and—most hazardous for him—too much success.

Like many upwardly mobile blacks, he felt guilty about the ghetto-dwellers he was leaving behind. Success had a way of calling forth his demons—his feelings of insecurity and unworthiness, compounded by others’ high expectations.

“I felt all those men in my family—Uncle Pinky, Uncle Spunky, Uncle Weldon, Uncle Bobby—every black man in this city, every black man that ever lived was riding on my shoulders. I can certainly see it as arrogance now, but at the time, I really felt I was representing the entire race.

“The way I dealt with, my fear was this: I decided there may be reporters at Channel 4 who are more experienced than me, and there may be reporters here who are smarter than me, but I swear to God in heaven, ain’t nobody in here going to work harder than me. And I really threw myself into my work.”

Vance envied the young white reporters he worked with—people like Bob Kur and Bob Hager—who could concentrate on their work without worrying how to live with themselves. “I had to decide, was I a black man who happened to be a reporter, or a reporter who was black? Until recently, nobody saw our side of it. We blacks were either non-persons or less than persons. I wanted to tell our side, so in the beginning I wanted all the black assignments. But after a year, I said wait a minute, I can do other stories, too.

“As time went on, I began to see diminishing borders and fences for myself. I realized pretty early that I could probably do okay in this business. But I had to resolve how to be comfortable with what I was doing, and Jesus, was it ever a struggle.

“There was a lot of pain that came with this career. And I don’t think I’m the Lone Ranger in this regard. And I am not the only or the worst casualty. I saw some good men go down and never come back because of trying to wrestle with all those questions.”

VANCE’S ANCHOR DEBUT it 1972 was not auspicious. He replaced a veteran white correspondent, Neil Boggs, who did not go quietly. Boggs complained that he was the victim of affirmative action, and the “salt and pepper” anchor team of Glenn Rinker and Jim Vance generated controversy.

“We got thousands of angry letters,” recalls Channel 4 operations manager Joel Albert. “They arrived in big cardboard boxes. In 30 years at the station, I never saw anything like it.”

To make matters worse, Vance had idolized Boggs, collecting his discarded scripts to study the way he wrote. “I considered it a hell of a way to have to start a job. ”

As an anchor, Vance felt even more pressure to be a faultless role model. “I would get so much advice, mostly from well-meaning blacks, about where I should go and what I should wear and what I should do.”

We are having lunch at La Tomate, a favorite restaurant of his near Dupont Circle, and he stops and points to his outfit—his Harley T-shirt and denim jacket. “This is me. If I could do this every day of my life, this is all you would ever see of me. I have never owned a pair of khakis in my life, but they were telling me that on weekends I had to wear khakis and loafers.

“And I remember people telling me I shouldn’t go to the bars on 14th Street. I love funky bars. Always have. I like places with wooden floors and the smell of whiskey. And if I can find a spittoon, I am really at home. It’s not that I was trying to prove anything. I was just comfortable in those places where people did not have a whole lot of pretentions.”

Kent Amos, who heads the Urban Family Institute and has been friends with Vance for more than 20 years, saw the conflict in the man. “He was trying to be the brother from Philadelphia I first met—a guy who went to a black school just like I did, who liked to play basketball, just a regular brother—and still be the persona of a television anchor. Don’t forget at that time, [Channel 9 anchorman] Max Robinson was still around. He was the polished, well-mannered type who more approximated a Peter Jennings. People wanted Vance to be more like Max.”

For the first two years, Vance tried on a variety of role models to see what fit. One day, he says, he sounded like Walter Cronkite. The next day, it would be Eric Sevareid. Then he would do a David Brinkley or a Howard K. Smith. “I was just going all over the place trying to figure out, what does an anchor sound like? I also had to figure out how black I was supposed to be.

“I remember the day I got normal on television. It was in 1974, at Christmastime, and the popular toy at the time was the Barbie Doll House. I had bought one for Amani, who was 4, and it was poorly designed. If you put the tabs together for the walls, there wasn’t enough space for the elevator to go up and down. So here I was at 5:30 AM, and my kid was going to be up in 20 minutes. I was in a panic. And luckily, I was able to devise something to make it work. But it was jerry-rigged.”

That Monday, when he went back to work, he was still upset. “The worst position a human being can be in is to disappoint your child on Christmas morning. And I had a sense there were probably a lot of people in the same position I was. So I asked the producer if I could have some time. He said yes, and they lit a spot on the front of the set where I could stand.

“I had it scripted, but all of a sudden, when I changed my mike and stood up there, I lost any concern about Cronkite, Brinkley, and all the rest of them. I was one pissed-off black father. I talked for about three minutes, and it ran over, and I didn’t care because as I got into it, my passion and my anger rose, along with all the other feelings you get when you’re concerned about your child.”

People accept somebody being down and dirty, if you will, if they think you are being honest

THE COMMENTARY STRUCK a nerve. And although Vance didn’t plan it that way, there is nothing better he could have done to help his career.

“From out of state people were calling and writing,” he says. “Mattel called and said, ‘We’re sorry. We goofed. Please tell everyone you can reach that we will give them their money back. We’ll give them whatever they want.’ That’s when I first learned what an impact television has. But more to the point, that is when it occurred to me that maybe all I gotta do is just be myself.

“But here’s where the contradictions of my life came in. At the same time, I was ashamed and terribly self-conscious, because I realized that I had let loose the dogs of [black] jargon. When I voiced those feelings, I did not try to use the best language. I did not try to present myself above reproach so nobody would ever be able to say, ‘See, them niggers still don’t know how to talk.’ I didn’t want Neil Boggs to be able to say, ‘I told you so.’ I was still smarting from that.

“What it came down to in the end was a realization that there is something unassailable about personal honesty. There’s a part of me you can’t hurt if I have been as honest as I can be. And number two, it sells. It works. People accept somebody being down and dirty, if you will, if they think you are being honest. It took a while for me to work it all out–actually, I still haven’t totally come to grips with the whole thing—but there finally came a time when it occurred to me that Max is Max and Vance is Vance, and not only can’t I be Max, but it’s okay to be Vance.”

THE COMMENTARIES helped Vance fight off boredom. He could spread his wings as a writer and get some of the anger out.

Sometimes he was whimsical; his pieces about ”Richard,” a giant cockroach with a unique way of looking at things, delighted many. Often he was moving, even poetic, but his commentaries on race and politics irritated many viewers. To them, Vance was an angry, uppity black man. Still, his bosses never told him what to write.

By the late ’70s, Vance was an institution. Nobody called him “Jimmy” or “Jim” anymore. He was “Vance,” even to his wife. But his personal life was starting to unravel.

In 1978, he separated from Barbara—they didn’t divorce until 1984—and moved to an apartment on Columbia Road in Adams Morgan. Nobody could accuse him of not looking cool, with his beard and beret, his Porsche, and his dog, an Akita he called Shogun. “I was livin’ large, as the saying goes, but I was also very, very unhappy. While my marriage had to end, I kind of enjoyed being married. And to ensure that Amani would never for a second think that this breakup was because of her, I spent every available moment with her.”

Vance and his 8-year-old sidekick became a familiar sight around Adams Morgan. He took her to the bars he frequented, like Manuel’s on 18th Street. Sometimes he would stop to talk to somebody on the way in, and Amani would head for the bar on her own, where they served her Shirley Temples.

“A half-hour later, I would look up and see her sitting there, with her legs crossed, holding a conversation. The kid could hang. I loved it.

“When 1979 rolled around, that was when I took my first hit off the pipe. I did it on two different occasions over several weeks. The third time, I’ll never forget. I was at this person’s house, and they asked me if I had any ‘blow.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, but I don’t want you cooking this stuff up, because’—and I remember saying these words—’you’re gonna waste my cocaine.’ Because I didn’t like freebasing.

“But on that occasion when I did it, something happened. I went to the moon, and it was a pleasant ride. Even after that, my drug use was casual, recreational, and it was all fun—for another year and a half. But when it went bad, it went bad in a big hurry. I mean, it was almost overnight. One day I couldn’t care less. The next day, it was like, ‘I gotta get some dope.'”

AT FIRST, Vance redoubled his efforts at work, putting more time into his commentaries and stepping up his charity appearances—”anything to hold on to the notion that I was still a worthwhile human being.”

But as his addiction got worse, his behavior became erratic. He would show up looking hung over, and he often seemed listless and bored on the air.

He knew his bosses realized his performance was off, and he was terrified they would find out the reason. “I was afraid to pick up the newspaper. I was especially terrified of the Sunday Post. Every Saturday night I had this terrible fear that I’d pick up the paper the next day and there would be the big exposé. I was afraid to answer my telephone. I was deathly afraid to open my mail at work, because I kept expecting to see letters, unsigned—’I know where you were. I saw you do this or that. I got evidence.’ It was a horrible life.”

The one bright spot in his life was Kathy McCampbell, who took over as producer of the 6 o’clock news in 1978. They became good friends and tennis buddies, but romance took a while to bloom. McCampbell is so fair-skinned—she is usually mistaken for white—that Vance held back.

“The blocker in my mind was her color,” he says. “I still felt rejectable.”

In 1981 they moved in together. The following year, Vance sought drug treatment for the first time, at Fair Oaks in Summit, New Jersey. Nobody knew about it except Kathy, Jim Van Messel, the Channel 4 news director and a close friend of Vance’s, and top NBC management in Washington and New York.

Against the objections of the doctors at Fair Oaks Vance left the facility at the end of three weeks. “Three weeks was all we figured we could afford for me to be away without raising the antenna of the Post and anyone else who might be interested. But it didn’t do me any good at all. Within 60 days, I was ‘out’ [on drugs] again.

“I never was an everyday user, but I was a hell of a binger. I would go weeks, even months at a time, and then I’d be gone for two days. There is a saying among people trying to recover that where one is too many, 1,000 is not enough. And that was the way it was with me. I can’t tell you how many times I would leave work at 11:30, clear in my mind I’m just going to go some place quick and then I’m going home. And then, about a day and a half later, I’m about as miserable as any human being can get. I’m out of money, I’m out of dope, and I’m totally, thoroughly embarrassed and disgusted with myself.”

AROUND THE END OF 1982, Vance got a call from Ed Bradley, a rising star at CBS in New York, who told Vance he wanted to come down and have dinner with him. By now Vance’s finances had been drained dry by cocaine, but he insisted on taking Bradley to Jean-Pierre on K Street and playing the big shot.

“We were just sitting there, talking the usual homeboy shit, and somewhere between dinner and dessert, Bradley said, ‘Vance, do you remember what Jim Brown said to Richard Pryor when he went to see him after Pryor set himself on fire [freebasing cocaine]? Well, what he said was, “Whatcha gonna do, Bro? Whatcha gonna do?”‘

“And I knew exactly what Ed Bradley was talking about, but I was so full of denial, I acted like, ‘What are you talking about?’ And then he went on to tell me what he had been hearing and the reason he was there. And here I’m thinking I’m so slick that none of my friends know what’s going on. And they were all scared to death for me.

”Of course, he didn’t get through to me, but what he did do—you know sometimes a guy never knows how many really good friends he has—he turned me on to his agent, Richard Liebner. And he said, ‘You gotta talk to this guy. One of the things you gotta do is get the money out of your hands. You gotta let somebody else handle it.’ And almost to placate my friend, who’s here trying to save my life, I say, ‘Okay, I’ll do that.”‘

In fact, Vance was within an inch of having to declare bankruptcy. Even after Liebner took over paying his mortgage and other bills, Vance found new ways to run up debts—and new enemies to fear.

“There were times when I had people after me with guns. I left town a couple of times because there were people looking for me who could hardly talk English, so there was no negotiating with them, if you know what l mean.

“Once I owed about $2,500, and I drove up to Philly on a weekday to see my aunts and uncles. You know, I really do revere those people. They gave up a lot for me, and they had put their hopes on me. And to go back to them when they’re old and retired and to ask for money they’ve worked so hard to get was one of the lowest points of my life. And they gave it all, too. And they didn’t ask me why. ”

THROUGH IT ALL, Kathy, Jim Van Messel, Richard Liebner, and a handful of others never gave up on him. Kathy especially was a rock.

“No human being on this earth has ever done more to salvage a life than she did for me,” says Vance. “Kathy could not save my life. She couldn’t make me want to live. But she would not let me die. There were times when Kathy physically would not let me out the door. I weigh 210 pounds, and she’s a 120-pound little thing. But the fierceness of her love was such that I could be intimidated by her.”

Sometimes, after a period of sobriety, Kathy would suspect he was relapsing, and she would call his old Cheyney State buddy, Ted Nickens, and tell him to hurry over. Nickens never lectured Vance, as so many others had. More often they cried and prayed together.

At work, Vance was moody and unapproachable. There were times when it was nearly impossible to get him to come out of his office to read the 20-second “teases” every afternoon from the newsroom. One of his bosses finally installed a strobe light in Vance’s office that could be switched on and off from the newsroom. The flashing light drove Vance nuts, and he would emerge cursing and fuming to do the promo.

Sometimes he left at the end of the 6 o’clock show and didn’t come back at all. Or he stayed gone for the next day or two. Sometimes he left at 7 and came back to do the 11 o’clock show as high as a kite. “Some of the worst, most desperate moments I’ve ever known were going on the air high. I would try so hard to appear to be okay, it was exhausting. And it was always accompanied by the feeling, ‘Everyone’s got to see through me. They have to know. I’m out here naked.’

“The other thing that terrified me when I would come back to work at 9 or 9:30 was seeing the light in the general manager’s office. I would drive in the parking lot, and the first thing I’d look to see was if that light was on, because my notion was if the light is on at 9:30, he’s up there trying to figure out a way to get rid of me.

“I’m trying to think, how the hell did I get through a day like that? And along with the fear, I was also trying to figure out how to get the money to get high again.”

MANY OF HIS CO-WORKERS had no idea Vance was in trouble. Newsrooms are frantic places, and most people are too wrapped up in their own work to notice much about colleagues. Besides, anchors are stars who are given a lot of latitude, and Vance had always hated doing teases.

People continued to use his office as a crying post, as they had for years. “Vance always had this great empathetic quality,” says Channel 4 entertainment critic Arch Campbell. “He was like some dean you would go to in college when you were feeling depressed. In retrospect, I think the way all of us brought our stuff to him contributed to the pressures on him, because he had his own stuff to worry about.”

Vance always had a soft-hearted side. Kathy recalls the time, before they were married, when she was hospitalized after breaking her back in a car accident. She had to lie flat in a back brace for weeks. “Jim never missed one day at the hospital. Sometimes he came a couple of times a day. One day he came in and I kind of had the blues. He had brought a felt-tip pen with him and he got up on a chair and drew a big heart on the ceiling that said, ‘Jimmy loves Kathy.’ You can imagine how wonderful it was to wake up and look at that every morning.”

At the same time, there was another aspect to Vance. “I never stole money from anyone, and I never picked up a gun in anger,” he says. “But I had this incredible dark side. It was never really harmful to others except indirectly. My dark side was totally directly aimed at me. There was a part of me that was determined to kill me. And I never knew it was there.”

My dark side was totally directly aimed at me. There was a part of me that was determined to kill me

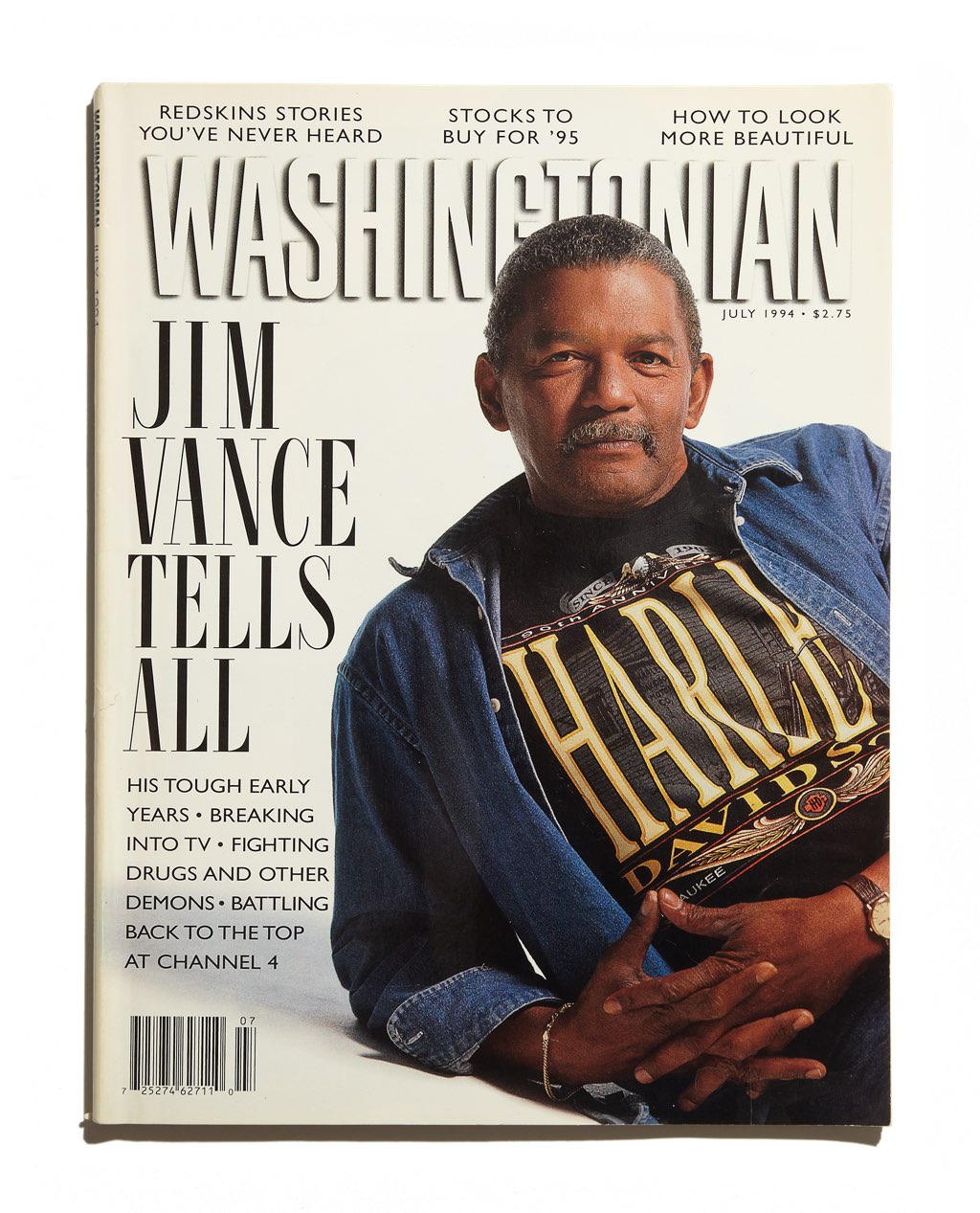

EARLY IN JANUARY 1985, at the urging of Kathy and Van Messel, Vance agreed to go to the Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage, California. This time, against the advice of everyone, he insisted that the public be told the truth.

His co-anchor at the time, Lea Thompson, was handed a slip of paper. “Reading that was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do in my whole life. I was fighting back tears the whole time because I wasn’t sure he’d ever come back,” she says.

In part, Vance’s statement said, “I am suffering from exhaustion, depression, and a dependency on drugs used to overcome these problems. I will be off the air for some period, and I am looking forward to returning to work as soon as my treatment at the Betty Ford Center is completed.”

Station management and the higher-ups in New York weighed cutting Vance loose, but Van Messel was adamant that he be given another chance. A short, gruff, no-nonsense guy, Van Messel had checked out doctors and facilities for Vance, accompanied him to Fair Oaks, and now visited him at Betty Ford. While Vance was away, Van Messel urged his friends to write to him, telling him why he needed to get well and come back.

At Betty Ford, Vance immersed himself in the 12-step self-help program, originally designed for alcoholics. It seemed to click. He stayed in treatment for five weeks, and he came back that February determined to stay clean. But one of his therapists at Betty Ford warned him he wasn’t out of the woods.

“She told me three things,” recalls Vance. “One was, ‘You’re a real clever guy. You can tell anybody anything they want to hear. But you’re not done yet. Two, when you get back to Washington, you’re going to get star-f—ed. You’ll become a celebrity for recovering. And number three, and this I can promise you, you will never, ever again in your life enjoy getting high. Once you know the kinds of things you’ve learned here, it will never be the same.’ And all three things she told me came right on down the line.”

BACK IN WASHINGTON, Vance was lionized for escaping the clutches of cocaine. Late in May he picked up the Washington Post Style section, and there was a huge picture of him above the fold. Underneath, two-inch high letters proclaimed: “Jim Vance, Renewed.” The implication was that he had done something great. He had already started to wonder himself if he hadn’t done something pretty heroic.

“Now, all this time, in spite of everything they told me at Betty Ford about needing to reinforce my efforts at recovery by attending 12-step groups, I didn’t want to bother going. I didn’t think I needed to bother. I still thought I was in control. But not long after that, I was invited to speak to some guys in a recovery program—it might have been on a Thursday night between shows—and I went and did it. And I was. . . .I was great. They gave me a standing ovation. And that standing ovation sent me right back out into the street. That night, I came back to the station, did the news, left at 11:30, and instead of turning right out of the parking light, I turned left and went straight to my dealer.”

In mid-June, Vance went “on the run,” as the junkies say, for three days. He finally hit bottom. He was deeply in debt. His expensive cars had been repossessed, and he barely had any decent clothes left. Mostly, he says, he was sick and tired of being sick and tired.

At 4:30 that morning, he went home, crept into the house so Kathy wouldn’t hear him, and got his hunting shotgun. He put it into the trunk of his car and drove out to the Maryland side of Great Falls.

“I was so utterly, totally done,” he says, “that I could not conceive of living through another minute of this nightmare. All my life I had been taught that the most important thing in life was being in control. I was the captain of my soul, the master of my fate. And to come to the full-face realization that it was all bullshit—that I had no control whatsoever, and that I was a complete —was devastating. So I loaded that thing and put both barrels in my mouth and put my thumb on the trigger. And I was not kidding. I was out of there. I could not stand the pain any longer.

“At the last moment, I didn’t do it. I ended up just crying a river. All of those years, I thought it was so important that no tears ever be shed from these eyes. And when the tears came, it was like 30-some years of tears I let loose. I couldn’t control it.

“To this day, I don’t know why I didn’t pull the trigger, but I don’t believe it has much to do with me. I consider without a shadow of a doubt that it was simply and purely the grace of God. I know people who did take their lives. There’s a whole bunch of dead folks who did nothing more than I did. Some did less. And for some reason, God didn’t choose to spare them. He chose to spare me.”

THAT SAME DAY, Vance’s bosses had decided they’d had enough. When Vance went back to the station, he was summoned to the office of general manager Fred De- Marco, who told Vance he was suspended. He could re-apply for his job in six months, DeMarco said, and they would decide then whether he’d be taken back.

Vance was hit by conflicting emotions. There was despair at the thought of all those years of work and the opportunity he’d been given going down the drain. But along with it came indescribable relief.

”I was finally free of the burden of lying and of trying to keep this front up, of leading these two lives. It was like my chains snapped and I was free.

“I left the station thinking I would probably never see it again, and went down to 5th and K to the Metropolis Club. It’s one of the oldest 12-step programs in the city, and it has a reputation for attracting really hard-core addicts. Across the street you can see the guys who hang out around the oil drums and drink Mad Dog 20-20. And I pulled up at this building, and it looked so grungy. I said, ‘I ain’t going in there.’

“Finally, I opened the door and saw this steep flight of stairs that I hope to my dying day I won’t forget—these old wooden stairs that sag and bow and creak, and crap all over the walls. There’s a lot of symbolism in that scene. A lot of guys remember those stairs at Metropolis.

“Anyway, I walked up those stairs and walked into the room, and I remember the utter humiliation of being there. I slunk to the back of the room as far as I could get and didn’t open my mouth. And after the meeting, some guys came over and said, ‘Man, are we glad to see you. We were praying that you would get here.’ They knew. I’m not sure earth people [non-users] knew how bad off I was. But they knew.”

That afternoon, Vance went to see Dr. William Flynn, head of Georgetown University Hospital’s alcohol-and-drug-abuse program, who had been counseling him. Flynn asked Vance what he wanted to do.

“That’s when I said, ‘I don’t know.’ I had never taken that position before. I always had some notion that I’ll go this far but I ain’t going no further. I always had a reservation or a condition. This time I was willing to do anything, go anywhere. I was perfectly willing to go to some treatment program and clean the lavatories if that’s what he wanted me to do. I felt no shame. That came later. At that point, when I totally surrendered, is when I guess I began to have a chance.”

FOR THE NEXT SIX MONTHS, Vance led a monastic existence, devoting almost every minute of the day to recovery. He moved to Potomac and broke up with Kathy. “I just felt I couldn’t subject her to any more pain,” he says.

All day long he went to appointments and meetings under Flynn’s supervision. He sought treatment daily at the Kolmac Clinic in Silver Spring, attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings at 11 a.m. each day, went to Narcotics Anonymous meetings at night, and began seeing a therapist three days a week.

Vance was still collecting a salary from the station, but the money went straight to New York, where Liebner saw to it that his rent, his children, and other necessities were taken care of. Vance got $50 a week to live on. “It was literally carfare,” he says, “because at that point, I didn’t have any cars. Even my motorcycle broke down, and I didn’t have the money to buy a new starter for it. So I would walk a quarter-mile over to the Ride-On and get the subway at Tuckermán Lane, and I’d take the subway to treatment or to therapy or to meetings at night. And I would try to get a ride back to someplace near where I lived. It was miserable.”

Vance had been advised not to leave town for treatment, and it was hard. “If I had seen George or Bob or Arch, I would have gone the other way. Because I wouldn’t have been able to look at them. The worst moments, short of that night at Great Falls, maybe even worse than walking into Metropolis that first day, were when I would get on a bus on Connecticut Avenue and have to face people who knew who I was. I’ll never forget the pain and utter shame of looking people in the eye, which I forced myself to do, and saying good morning or good afternoon. That was real important to my recovery. To own that shame. To own my fear and face it.”

The two people he desperately wanted to keep in his life were Dawn and Amani. “I was hardly eating at the time. I wasn’t interested in food until later. But I wanted them to want to come to see me, so I would go out and buy a whole bunch of food—bananas, oranges, apples, canteloupes, all sorts of things I don’t even eat. And they’d come, and maybe Dawn would eat an orange. And the rest of the stuff would just go bad. But I’d buy more. That’s what you do when you’re a parent. You make sure your kids have something to eat if they want it.”

AT WRC, some colleagues, especially those who had been forced to cover for Vance for so long, were angry at him for blowing so many chances. Others mourned him almost as if he had died. George Michael was particularly upset, in part because of their friendship and in part because Michael believed Vance was an integral part of his own success at Channel 4. “I walked into the general manager’s office and said, ‘Do the decent thing and tear up my contract. I want out,'” says Michael. “The largest part of my professional life was Vance. And there was no guarantee he’d come back.”

One person who believed otherwise was Van Messel. When he was interviewing Kris Ostrowski for the job of assistant news director that fall, he made sure she met Vance before sealing the deal. “Van Messel took me to some little café on Connecticut Avenue, and there was Vance sitting at a table, reading a book,” says Ostrowski. “I think he wanted to make sure that when Vance came back, he and I were comfortable with each other, which we were. ”

On January 11, 1986, the suspension was over, and WRC took Vance back. This time his bosses watched him carefully. Everybody, including Vance, knew it was his last chance. In the newsroom everyone was glad to see him, but the reception was low-key. He wanted it that way. “Those of us who know him can sense when he needs space, and everybody gave him plenty of it,” says Arch Campbell.

The following year, Vance and Kathy were married. He continued to work at recovery, going to AA or NA meetings every day and continuing to see his therapist. “I had eschewed therapy for a long time,” he says. “It was that macho thing again. If I got a problem, I’m supposed to be able to fix it. But I finally did go, thank God, and what I learned was a revelation.”

For the first time, Vance was able to come to grips with the rage and shame he’d been carrying since childhood, such as the resentment he bore towards his uncles.

“My uncles were all Depression people, ” he says. “They lived at a time before Brown v. Board of Education, when there were places they couldn’t go and barriers they had to accept. They could remember when abusing blacks was Saturday-night sport. And all they were trying to do was prepare me for the world as it was in those days. Even though it was beginning to change, they knew I wasn’t going to have it easy, and they wanted me to be ready. And I love them for that now. I didn’t love them for it then.”

He was urged to examine the anger he bore towards whites for the tragedy of his father, who was good enough to fight on the front lines in World War II but was refused admission to the plumbers’ union when he got back and drank himself to death at the age of 38.

“I was convinced I was the scum of the earth,” he says. “My father didn’t want me, and that’s why he died. My mother didn’t want me, and that’s why she left me with my grandparents and went to Philly, in spite of all the shit she was giving me about the schools being better in Ardmore and having somebody at home all the time. I wanted to go with her. I did not know that.

“I didn’t know that I hated myself, that I spent all of those years trying to live down to my expectations of myself while at the same time trying to live up to everybody else’s expectations for me. My most dangerous times were after I’d done well. After a really good commentary, when people were calling and lavishing praise on me, that was the night I would be most dangerous to myself. I’d have to go out and prove everybody was wrong, that this bad person was the real me.

“It was the same with that gang foolishness. I would make a couple of zip guns or zappers the same night I had done well on an SAT test. If I had a good football game, that night I’d be out looking for a fight. It was the strangest life, and I wish I could have done it differently, because I spent most of my life being ripped apart.”

He learned that his thirst for danger was not the exuberance of youth but part of his darker side. “I remember talking in therapy about how I needed to exorcise my dark side, this other person inside there. And they told me that I will never exorcise my demons. Nobody ever does. The point is to manage them, to control them and not let them control you.”

IT TOOK A WHILE for Vance to regain his standing with the audience. It was a year, for example, before Bret Marcus, the new news director, and Vance agreed it was okay to resume doing commentary. ‘ ‘I came back with a considerable sense of humility,” Vance says. “I really made a conscious effort to regain the respect and the trust of people whose faces I never see, but whose trust and respect I want desperately, not just as a professional, but as a man, as a human being.”

To this day, according to station sources, there are some viewers who will never forgive or forget that Vance had a drug problem. But their numbers have dwindled.

In 1988, the station did a survey to try to find out why Channel 4 could not overtake Channel 9 at 6 o’clock, despite leading at 11 o’clock. Some of the findings pointed to Vance, but it was not because of his struggle with cocaine. The consultants found that the Channel 4 broadcasts had too many “edges”—aspects that irritated people. One edge was Vance’s commentaries; people thought he was too opinionated. The locker-room banter between Vance and Michael was another; women felt excluded. Vance’s co-anchor, Dave Marash, especially his beard, was a third edge. Viewers also complained about having to watch too much blood and guts on the newscasts.

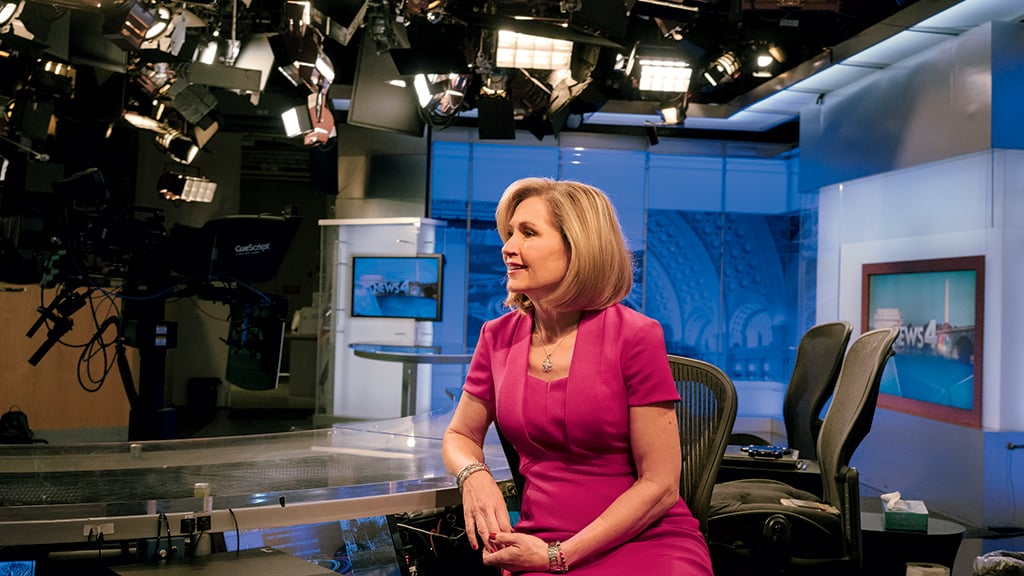

The station responded by replacing Dave Marash with Doreen Gentzler, who quickly proved popular with the audience. To Vance’s dismay, management also put a stop to his commentaries. He and Michael were told to tone down their act. And fewer police-blotter stories were assigned.

The ratings were not affected much. The station never has overtaken Channel 9 at 6 o’clock, except during the Barry saga in 1989 and 1990, when WRC was consistently ahead on the story, thanks to the heavyweight reporting team of Tom Sherwood, Pat Collins, Joe Johns, and Jack Cloherty. Vance was the glue that held them together, attending every strategy session and anchoring hour upon hour of live coverage—his forte as an anchor. Despite his personal agony at seeing the mayor and his weaknesses stripped bare, professionally Vance was in his element.

By 1992, studies showed he was Washington’s most popular TV-news personality. Station executives tend to credit Gentzler with “softening” Vance, but the truth is probably more layered.

To some extent, Vance’s stature is attributable to his sheer longevity. The only anchor who has been around as long is Channel 9 anchorman Gordon Peterson. In addition, Vance projects an authenticity that viewers sense. He’s certainly not the best reader on TV; for 25 years producers have been trying to get him to put more energy into his delivery. And he’s pretty bad at forced chit-chat. But give him something to talk about that excites his curiosity or his passion—home rule, sports, black holes in the universe—and he comes alive. His eyes sparkle, his enthusiasm is infectious. In a medium full of hype, Vance is the no-bullshit guy. This makes it hard for him to stomach some of the silly, reactive stories on local news.

He chafes at the changes he has seen at Channel 4, which has lost many of its most experienced reporters, writers, and producers in recent years. He does what he can, pressing his point with the news director and the general manager, almost always behind closed doors. “He’s known as the Velvet Fist,” says reporter Tom Sherwood. Vance attends the daily assignment meeting at 9 a.m.—almost unheard of for an anchor who does the 6 and 11 o’clock news—where he is seen as a guardian of journalistic values.

“Jim has this wonderful long lens of personal and professional experience in his life, in Washington, and in journalism,” says Channel 4 news director Dick Reingold. “When he speaks, his opinions are given a lot of weight, not because he’s the anchor but because he’s Jim Vance.”

One thing Vance does with the full support of his bosses is his weekly segment “Everyday Heroes,” chronicling the deeds of ordinary people—often blacks—who make a difference in their schools, churches, or communities—a subject he feels strongly about. “If somebody came here from another planet and looked at our news, the totality of their awareness about black people would have to do with pathology,” he says.

For all the good he feels he can do, 25 years on television is a long time, and Vance, whose contract is up this year, says he thinks he’ll be ready to move on to something new in four or fïve years.

“I certainly don’t expect to be celebrating my 50th anniversary at WRC,” he laughs. “Or my 40th. Or my 35th.”

THEY SAY THE LEOPARD never changes its spots, and in many ways Vance is the same person he always was—a warm, generous, disorganized guy who can’t say no and winds up forgetting half the stuff he has promised to do. Don’t bother to leave a message on his answering machine, because he seldom checks it. “I’m still the same asshole l always was, ” he cheerfully admits.

He still has a hard time staying in one place. You can see it on the set when he drums his fingers. But the people who are close to him say he is less restless than he used to be.

“Vance has become very mellow, very sweet, very gentle in the past few years,” says Kathy McCampbell. “What he’s doing now is making time for himself. He takes on less than he used to, and it’s really helped to make him a happier person.

“In the past he always had to be on the go, doing speeches, doing work, and what not. But now, there’s the dimension of peacefulness that he has learned to go out and get for himself. ”

One source of satisfaction is his children. Dawn, 33, is a newsletter editor and lives in Silver Spring. She got married last year, and her doting dad was delighted to play host to 500 guests at her wedding reception at Strathmore Hall in Rockville. Amani, 24, is an assistant buyer for a retail company in New York, and she’s constantly on the phone to her father, when she isn’t visiting. Brendon, who became the son Vance never had, just graduated from St. Albans and is headed for Morehouse College in Atlanta this fall.

“I used to beat the hell out of myself for not being the best father that the world has ever known, but the proof that I didn’t do that badly after all is the fact that I have some absolutely delightful kids. They’re dynamite people with their feet on the ground who anybody would be proud to have as neighbors.”

Vance sees a lot more of his aunts and uncles these days, too, after beìng virtually estranged from them for many years. “One of the biggest thrills I’ve had was to have seven of them down here, staying in this house, two years ago when Clinton was inaugurated. We got the limos for them and tickets for all the functions and inaugural balls and whatnot. And man, that was so good, just to be able to say, ‘You all come on and let me do the best I can to say how grateful I am for everything you did for me.”‘

Vance never lost touch with his mother, but their relationship was strained. He hated to pick up the phone when she called. She died in 1988, but now, he says, he’s made his peace with her. “It was like a rock being lifted from my chest,” he says. “Basically, what I have come to do is forgive her for anything about which I had resentment, and to acknowledge that whatever her faults, she did the best she could.”

Now Vance is ready to close more circles. There are letters he wants to write to Ed Bradley and others he cut off. “I want to tell them how important they’ve been to my life, and how sorry I am for not letting them know. I want to do that as much for myself as for them.”

the proof that I didn’t do that badly after all is the fact that I have some absolutely delightful kids

OUTSIDE WORK, Vance leads a quiet life. He and Kathy like to play tennis, usually on the public courts on Van Ness Street, or go to a movie. When they go out to dinner, they favor low-key places like Negril in Bethesda or La Tomate, whose proprietor, George Koropoulos, is a long-time buddy.

The Vances throw the occasional big party, but they don’t entertain much. He would rather spend his free time reading a book—he is a voracious reader of novels and talks about writing one—or doing something like laying tile on his sun porch. “He’s always ripping something out and putting something new in,” says McCampbell, who complains that he starts jobs he doesn’t finish.

Vance finds peace out on the water, too. He keeps a 12-foot John Boat on the lake at Airlie Plantation; sometimes he’ll drive down early in the morning and fish by himself. He has a 25-foot cabin cruiser in Annapolis. Or he may haul his bass boat down to the Potomac; he seems to know every inch of the river. No faithful Channel 4 viewer is likely to forget how excited he got a couple of years ago when then-President George Bush accepted his offer to show him some good fishing spots on the Potomac. The two men fished together several times.

VANCE’S FAVORITE ESCAPE is cruising the back roads beyond the Beltway on his Harley-Davidson Fatboy. It’s the Cadillac of motorcycles—the bike Arnold Schwarzenegger rode in Terminator 2. Vance’s has about $8,000 in accessories—extra chrome, sissy bar, back rest, windshield. “My bike saves me thousands of dollars in shrink fees,” he says.

Riding it brings him peace of mind, freedom, anonymity—and something he still can’t entirely resist, the thrill of danger. “It lets the kid out,” he says. “And yes, it does appeal to whatever sense of macho I still have in me. I love that roar, that vibration when I get up to certain speeds. And I love the way some people look at me. They don’t see Jim Vance the anchorman. They see some biker guy, and I see both fear and envy in their eyes, which gives me joy. There’s nothing to fear, but there sure as hell is plenty to envy.”

”I consider myself to be blessed beyond measure, but deservedly so. It’s like the struggle I had being comfortable with becoming a reasonably successful black man. I never in my life, for 40-some years, had the notion that I deserved good things. Even still, I’m not sure I accept the notion. When I bought that Mercedes, the first six months with that car, each day I threatened to take it back. It’s like, ‘I do not belong in this car.’ I was not comfortable in it. Not today, though. Not today. Today I jump in, put the top down, and ride around with the biggest grin you can imagine.”

ONE THING VANCE is not smug about is recovery. He knows too much. After eight years of being clean, he still goes to an AA, NA, or CA (Cocaine Anonymous) meeting nearly every day. “When you’re recovering, the compulsion to use again is constant. Then it fades. But it never goes away altogether. In the literature, they say the disease is cunning, baffling, and powerful, and now they’ve added a fourth one. It’s patient. It will wait for you. I’ve long since lost the compulsions and the dreams about using, but I can still ride around certain places or neighboroods and get a feeling deep in my gut that is terrifying. There are places I have not been in seven years—places I won’t go again. Not that I’m afraid that going into a certain bar would create temptation. It’s just that there are a lot of things I have left behind me that I don’t need to revisit.

“One of the things I treasure most about what I’ve learned is that concept of taking one day at a time. I am so grateful that all I have to do is to get through every day. I can handle that. There were times in recovery when I was not able to t4ke a day at a time. It was, ‘Let me get through this next 30 minutes.”‘

Vance also has had some somber reminders of the need not to let down his guard. Last year four friends who had been off drugs or alcohol—for 9, 13, l7, and 22 years—went back again. “Three of them died within six months of going back out,” he says.

While Vance has cut back on his public appearances, he doesn’t stint on his efforts to combat drug abuse. He is one of the founders of the Columbia Recovery Center, a self-help group for alcoholics and drug addicts at 14th and V streets, Northwest, where he has done everything from counseling individual addicts to buying the folding chairs at Hechinger. And he always finds time to talk to young people who are either in treatment or at risk of using drugs.

“His talk was simply phenomenal,” says Diane Albert, a teacher at the Mark Twain School for emotionally disturbed youngsters, where Vance spoke not long ago. “Our kids do not sit still for very long, but when he talked about his own personal traumas, they did not move a muscle.”

What does he tell kids? “I don’t tell them not to do drugs or not to drink. I try not to bullshit them with any blanket horror stories about what it will do to you if you drink a beer. I got way too much respect for kids to do that. All I do is tell them my story. I share with them my pain. I share with them the horror of my life.

“Neither do I try to bullshit them in terms of the particulars of my story. I will tell them about being naked in a basement with roaches crawling all over the place, and I don’t care, I just want another hit. I will tell them about that shotgun in my mouth.

“I try to stress our similarities at the same age, whether they are black or white, from Montgomery County or Prince George’s, and I make sure they understand what I was feeling at that time. And that when I drank, it was because that’s what the cool people were doing, and I really wanted to be cool. When I smoked marijuana, that’s what the cool people were doing, and I wanted to be a part of that. And when I did my first cocaine, how that shit hit me in the back of my head, but I had to be cool. And how being cool kicked my natural black ass. And I tell them just like that, not to get down and hip with them, but to make it plain. I tell them how hard it is to shake.

“But I share the up side with them, too—what my life is like now, not only without the drugs, but without the psychological burdens that came with drug use. I tell them how liberating it is to be able to forgive myself for something I might have done wrong. And how wonderful it is not to feel that I have to be something I can’t ever be. Like perfect.”