It was just before 9 am on July 22 when Doreen Gentzler got the call. She was at home in Chevy Chase and still asleep, a luxury the Channel 4 anchor allowed herself on Saturdays. Her husband, Bill Miller, nudged her awake, then headed back down to the kitchen. A few minutes later, she appeared at the foot of the stairs, still in her pajamas. She stood there and said quietly: “Vance passed away.”

In the spring, Jim Vance—the 75-year-old lion of Washington TV journalism—had privately revealed to Gentzler, and later to his News4 viewers, that he had Stage 4 lung cancer. Gentzler remembers absorbing the news soberly, understanding that she didn’t have a lot of time left with her beloved colleague. Now the day had come.

She didn’t yet register that her life had changed drastically. “One of her first thoughts was that she needed to talk to her colleagues and get to work,” Miller remembers.

Within half an hour, Gentzler was on a conference call with her bosses. They strategized the station’s announcement, which needed to be quick, as the news was already cropping up on Facebook. Soon everyone was racing to the Channel 4 offices on Nebraska Avenue.

Gentzler walked to her desk—the one right across from Vance’s. As coworkers buzzed around her, many blotting their eyes with Kleenex, she started working up her script. Her bosses had informed her that she would anchor the segment on Vance’s death that evening.

As Gentzler passed out hugs in between writing her lines, it was as though she already understood the weight of her responsibility: to be the ballast not just for those in the newsroom but for her viewers, too. After all, Vance was a hometown hero—he had filled Washington’s living rooms with his born-for-TV personality for the last 50 years. In the ’80s, he’d even endeared himself to viewers by coming clean about his cocaine addiction and stints in rehab. Gentzler had been Vance’s on-air partner and confidant for 28 of those years, half of a duo so dominant that Washingtonians referred to them simply as “Jim and Doreen.”

She focused her mind that morning on George Michael, the channel’s late sportscaster. When he died in 2009, Vance led a moving piece on their decades of working together. “Vance did this for George,” Gentzler says she repeated to herself. “I’m going to do this for Vance, and I’m going to make sure we do it right.”

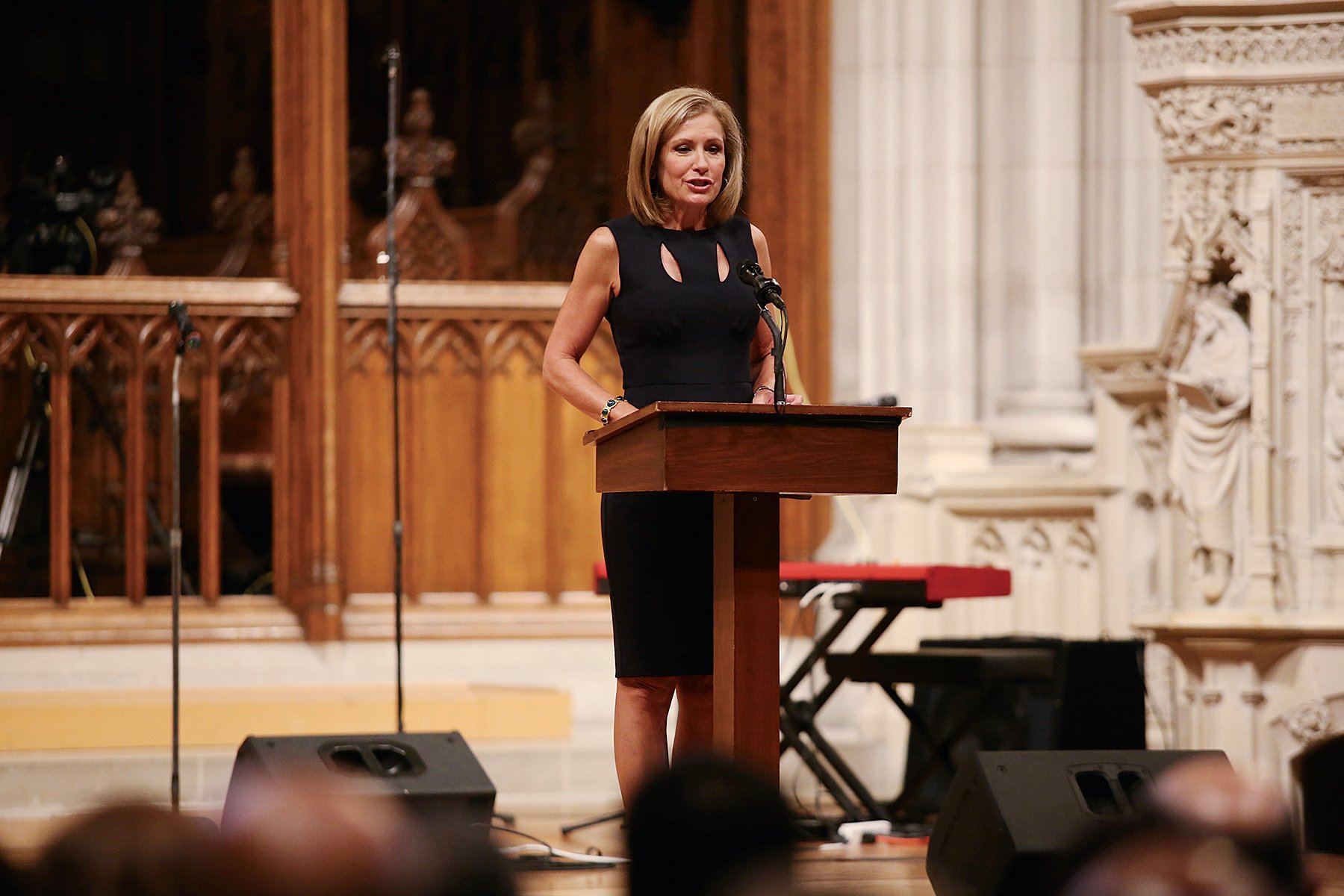

That evening, wearing a black sheath, Gentzler reminisced about Vance’s “smooth voice and calm presence,” how he loved Harleys and fishing and sports. She talked about his reporting on critical moments in Washington history, from Watergate to Marion Barry’s arrest. Because it’s TV, where the presenters are part of the story, she also talked about their friendship, how much they loved to “make each other laugh.” Then she signed off.

Gentzler was the same steady and warm presence she is every night. All the while, her coworkers, watching from behind the cameras, struggled not to cry. “I couldn’t even begin to understand how she was able to do it,” her colleague Eun Yang says.

The scene would repeat itself in the weeks and months ahead—the entire Channel 4 newsroom leaning on Gentzler. Yet shouldering the grief of her colleagues and a whole community meant Gentzler would struggle to access her own. With Vance’s passing, she may have become the station’s “queen,” as Yang puts it—the face of local news across Washington—but she had also become something like a widow. And how do you square reaching the zenith of your career while managing a grief intensely and irrevocably tied to that career? Six months later, Gentzler still doesn’t know—the pain of Vance’s death is still too deep to confront entirely.

“It’s up to me to figure out how to protect myself. But I don’t know what that—” She pauses to take a breath. “I’m still trying to figure out what that looks like.”

Allan Horlick was very, very stressed. It was early 1989, and Channel 4’s general manager had been plugging away at the station’s 11 pm lineup for two years with little to show for it. He had the region’s best news talent—Vance, Michael, and meteorologist Bob Ryan—yet Channel 4 still couldn’t climb out of third place in the ratings. It’s “literally painful,” Horlick says, to remember those nights he’d get into bed and turn on the broadcast. His wife would elbow him and point at the testosterone-fueled panel and say, “Do you see anything wrong with this picture?”

“It was painfully obvious that in spite of the immense talent . . . it was just flat. It was like an old boys’ club,” Horlick says. “I knew we needed a spark plug. We needed a strong woman.”

How do you grieve a work husband? How do you mourn a work wife? We rarely consider what it might be like when our work spouses die. Why is that?

Gentzler’s name popped up early in his search. She had enjoyed some success as an anchor for Cleveland’s NBC affiliate. “She was, in a word, natural,” Horlick remembers. “You just saw this smart, honest person who you trusted to tell it like it is.”

But as he kept digging, Horlick’s enthusiasm waned. Gentzler had just started a new job anchoring weekend broadcasts for the CBS station in Philadelphia, where she seemed entirely different from the fresh-faced, dogged reporter Horlick had seen in Cleveland. “In Philly, it was like [her bosses] had a preconceived notion of what an anchor should look like,” he says. She was stiff and came off as unfriendly. She wore over-the-top costume brooches, “Republican helmet hair,” and “ridiculous blouses” with necklines up to her chin. Horlick cut her from his shortlist.

Gentzler herself wasn’t pleased with her new on-air persona. She dreaded going to the newsroom, a toxic atmosphere that she says took a toll on her mental health. An Arlington native, she coveted the Channel 4 gig. Not only was it a dream job—a huge market with big-name anchors—but it would bring her back home.

So when Gentzler learned through the grapevine that Horlick was reluctant to hire her, she wrangled his phone number and called him at home. The first thing she said: “Why won’t you talk to me?”

“I said, ‘You know, Doreen, I don’t like the Philadelphia Doreen—I loved the Cleveland Doreen,’ ” he remembers telling her. “She said, ‘That’s the real me! They won’t let me be me!’ ”

Gentzler’s punchy tone—and the audacity of the call itself—was a key factor in convincing Horlick she was worth considering. “The biggest concern was finding someone who could hold her own against big personalities like Vance and George Michael,” he says. “I knew after hanging up that Doreen was someone who could.”

Gentzler wasn’t a likely sidekick for Vance. She was 31—16 years his junior—and hardly known for the antics that defined his newscasts with Michael and Ryan. When she and Vance first met over dinner at La Ferme in Chevy Chase, nerves scissored through her. He was skeptical himself. When he spotted Gentzler in the restaurant’s parking lot, he’d later admit, he thought, “Well, at least they hired a fox.”

But she was sharp, and people on the set were quick to notice. “Take a good look,” Vance said during their first broadcast together. “She’s going to be with us quite a while.”

Gentzler’s immediate appeal, Horlick says, was being the “adult” in the room and breaking up the long runs of Vance and Michael just bantering on the air about “ridiculous guy stuff.”

“She’d let it go on for a bit, and then she’d be like, ‘All right, guys, we get it. We’re moving on.’ ”

It’s that “seriousness of purpose” that longtime Channel 4 reporter Tom Sherwood, then at the Washington Post, remembers well. He says that the smarts and energy she brought to the newsroom helped lure him to the station. “After they hired her, I got a call from [reporter] Pat Collins, and he said, ‘Sherwood, we just hired a new anchor, and she’s not a bimbo.’ ”

In short, the newscast’s ratings shot up, in part because of good timing: Seven months into Gentzler’s tenure, Mayor Barry was arrested on drug charges, and his first call to a reporter was to Vance. Channel 4 owned the weeks of coverage that followed. (“When the homegirl came back home,” Vance later said, “that’s when we started winning.”)

The pair steadily began to peel away viewers from Channel 9, and to keep them all week. For Horlick, watching their relationship develop was rewarding as a manager: “You just never know, when you’re pairing people, whether it will develop into magic. You just get lucky.”

Which makes it hard to distill the particular alchemy of Jim and Doreen. Television requires on-air personalities to act out a simulacrum of family life. But it’s not as though Vance and Gentzler’s tastes and experiences made them naturals for the role. They weren’t weekend comrades—he liked to take trips on his Harley; she liked to bike around the monuments and go on hikes with her dog.

“It wasn’t like they were drinking buddies,” her husband says. “But I think for the core traits that define somebody, they were basically the same. They were both very calm in a crisis. They both had a terrific sense of humor.”

Vance and Gentzler confided in each other about personal matters, drama involving their spouses, or her two children and his three. “I’d have some issue with my husband, and he’d take my husband’s side, every time,” Gentzler says with a laugh. She’d give Vance advice, and he’d groan, “Goddammit, that’s exactly what my wife said.” They’d bicker about why they were leading with the weather again. She’d warn him to stop smoking around her when she was pregnant.

“When you have makeup people dolling you up every night, making sure you have water and a seat and you’re pampered, you can misinterpret that as an indication that you’re actually special,” Sherwood says. “She’s never misinterpreted that she’s somebody special. She’s Doreen. And Jim was Jim.”

“To be honest, I was not prepared for how public the grief process through all of this would be. I didn’t really appreciate that everybody would be looking at me.”

Their longevity only served to cement their place at the top. “A lot of dominance is due to habits,” Horlick explains. “People who are now in their twenties, thirties, forties, and fifties started to grow up with Jim and Doreen—that’s what makes a brand.” By 2014, the Post was reporting that the pair regularly drew more viewers in the Washington area than MSNBC, CNN, and Fox News together—affirming the old line that people don’t watch the news; they watch the people on the news.

For Gentzler, one of their most memorable moments came during President Obama’s 2008 Election Night. She and Vance sat on the set, blissfully stumped about whether they should take the first live shot of the Obamas coming onstage at their victory party or of the wild celebration on U Street. “He never imagined, and neither did I, that we’d see a black man elected President in our lifetime,” she says. “But to experience that through his lens . . . .” Her voice trails off. “So when Hillary Clinton was nominated at the convention, we watched her speech together, and I think we both expected we’d be working together to see the first woman elected President, too.”

Instead, Gentzler says she leaned heavily on Vance after Donald Trump’s election. She struggled with the “shell shock” of his win and what she thought would come of his presidency: “It’s just like, ‘Uh, what? He’s going to start a war with North Korea? He’s gonna kick the young immigrants out?’ It was just one thing after the other. It never lets up.”

Vance, she says, “always found the positive view.” Recalling this, she laughs and shakes her head at the improbability of it all. “I mean, who’s had time to stop and think about how this can have a positive outcome?”

Then she turns her head, closes her eyes, and puts her hand over her mouth because, sitting outside Raku in Cleveland Park, she has just started crying.

Recalling those conversations is difficult—not so much because of their content but because they took place in Vance’s last few months alive. He told Gentzler about his diagnosis last April. Though their desks were in the middle of the newsroom—they both liked to be amid the action—they also shared an office outside it. That day, Vance motioned for Gentzler to follow him in there. “Let’s talk,” he said.

Gentzler remembers him being “very strong . . . trying not to get me upset.” He relayed what he knew, which at the time was little. She switched into journalist mode: Who’s your doctor? Are you sure you’re with the right one? Are you investigating different treatments? Can I look into this?

He chuckled and waved her off, told her just to let them see where things would go. From there, as his treatments got under way, his presence in the newsroom became hard to predict. One day he’d be in, Gentzler says, anchoring the 6 o’clock with her, his usual self; the next he’d be out, suffering from the side effects of chemo. In many ways, things stayed the same—until, of course, the day they weren’t.

How do you grieve a work husband? How do you mourn a work wife? The rituals after the death of a family member are so firmly defined: paid leave from work, Hallmark cards bearing witness to the void, empathy from friends who have likely experienced something similar. Yet rarely do we stop to consider—in our society ordered around the 9-to-5, where our coworkers are often more intimately entwined in our day-to-day than our actual partners—what it might be like when our work spouses die. Why is that?

Maybe it’s because we’re somehow taught to grant professional figures immunity from the banalities of daily existence. We all know that feeling of glee, or perhaps confusion or discomfort, when we spot a colleague out dancing on a Friday night or walking into the office one morning with eyes swollen from crying—as though the curtain has been jerked back on some terrific secret. It’s as if we’re programmed to assume our coworkers aren’t prey to life, much less death. But maybe it’s also because many of our workplaces have become so transient, pit stops where those passing through wouldn’t experience the death of a colleague with the same intensity and devastation as they would a family member.

Channel 4 seems somehow different, a place whose employees have worked together for decades. For many, that has made Vance’s passing easier. But not for Gentzler. Her coworkers, not to mention the station’s many viewers, haven’t been shy about confiding in her and about looking to her as a surrogate for stability. It was telling that in the immediate aftermath of Vance’s death, as many in the newsroom nursed their own heartache or pushed forward with their work, Gentzler sat at her computer thanking and encouraging the hundreds of viewers who had posted about their devastation across social media.

“You can tell there’s a lot of responsibility on her to be a steward of his memory,” says her colleague Aaron Gilchrist. “We knew his death had an impact on her at a really personal level, but somehow she’s mustered the strength to be really strong for everyone else.”

Yet she’s also human. And part of the challenge of being a public figure, she reflects, especially in moments of darkness, is maintaining the awareness that many people, selfishly or not, rely on you for reassurance that everything’s going to be fine.

“To be really honest,” Gentzler says, “I was not prepared for how public the grief process through all of this would be. You know how, normally you go through your head and ask, ‘Okay, what happens next? And how will it affect me? And how will I respond?’ I thought about that, but only in a very vague way. I didn’t really appreciate that everybody would be looking at me for those answers so fast.”

So she has nursed her sadness in bits and pieces. She asked for a day off in the week after his death. On that day, she didn’t look at e-mail and didn’t respond to upset viewers flooding her social media. She biked to Hains Point, just off the Jefferson Memorial beside the Potomac. She likes it best during the week, when it’s quiet and the traffic is light and few people are around. “I cried a lot,” she says. Her thoughts were amorphous and big, but she cried hardest when she thought of his laugh.

However, the reality of working in the news business is that the show must go on. So she’s still largely in her “public mode.” NBC4 still hasn’t settled on Vance’s replacement, so Gentzler works with a rotating cast of co-anchors for the 6 o’clock show. “I certainly like all of those people I’m anchoring with,” she says. But it’s also true that a rhythm has been broken: “I liked it the way it was.” No longer is she palling around with her old partner before airtime.

“She’s had to go into this mode where she’s had to be the face of an entire region’s grief,” says Eun Yang. “I hope, finally, when the smoke clears, she’ll be able to take more time on her own, for her own grief personally.”

There are so many things Gentzler can’t remember right now, things she knows she’ll one day have to redraw but that for now feel shapeless and dark. Such as her last show with Vance. She can’t remember what it was. How is that? “Because even after he shared the news,” Gentzler says, “I never let myself think that every broadcast could be our last broadcast.”

As the final member of the Jim-and-Doreen-and-George-and-Bob franchise that owned Washington news throughout the ’90s and early aughts, Doreen Gentzler has unequivocally become the station’s biggest star, the keeper of its legacy. News4 is now just Doreen—and, for her, all the pressure that comes with that.

“I think Vance and I had a very good partnership, where I always felt like we were equals on the set, and I was happy with that,” she says. “But now I have just a little more responsibility, I think, in carrying that—I don’t know how to put this without sounding like a jerk . . . .”

She clarifies: “There’s the brand of NBC4, of News4. I feel a little more responsibility in that regard, now that he is no longer here.”

You can’t blame her. Even as someone who captured the loyalty of viewers long before cord-cutting and a whole generation who consume their news online, Gentzler’s responsibility for ensuring the station’s dominance is in no way assured.

Channel 4’s 6 pm broadcast struggled during the summer and dropped from number one. Last fall was better: From October to December, the newscast climbed back on top, edging out Channel 7, according to ratings pulled from Nielsen. The broadcast’s ratings continue to hold steady—in part because, as one NBC4 source puts it, “numbers spike sharply in bad weather.” But it remains to be seen whether Gentzler’s warmth and longevity are enough to maintain the lead, minus the dazzle of Vance, in a changing news market.

“We are always concerned about losing viewers,” Gentzler says. “Our audience is shrinking. They can get the news anytime on their phones and on their tablets, so anybody who is in the television news business who tells you they’re not concerned about losing viewers would be kind of a fool.”

In early December, the whole station gathered in front of their building, NBC’s peacock logo prominently displayed overhead. They were shooting a promo that would run during the Super Bowl. Management positioned Gentzler out in front. It was a perch that any news anchor would covet—the face of the top-rated station in a major market. Yet Gentzler says she couldn’t help but feel sad.

“They put me out front, by myself,” she says. “That should’ve been the two of us.”

Not all of her colleagues were thinking that. “She’s the leader of the newsroom now,” says Eun Yang. “And I think Vance would agree.”

This article appears in the February 2018 issue of Washingtonian.