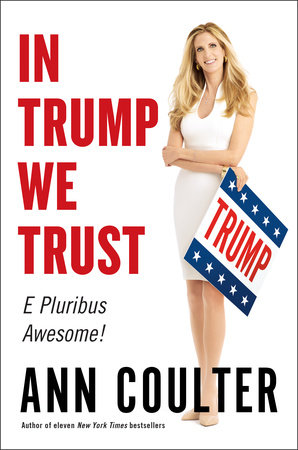

On a balmy day this past June, I meet Ann Coulter at a seventh-floor studio in lower Manhattan. She has just finished writing In Trump We Trust: E Pluribus Awesome!, her hasty manifesto in support of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. Now, she’s posing against a white tapestry in a white body-con dress, a red “Make America Great Again” cap perched over her shoulder. It’s time for the book’s cover shoot, and I am here to watch.

“Try being a little bitchy,” says her longtime photographer, Shonna. (When I arrived, Coulter introduced us, pronouncing it Sh-own-a. Behind her Shonna mouthed, ‘That’s not how you say it.”)

Coulter tosses her hair, gold and glowing under the white lights. “I’m never bitchy!”

She looks ethereal in this white-drenched room. The studio hands position a fan off-camera. They switch it on and her hair lifts and ripples behind her. “Yes yes yes,” Shonna-not-Showna croons. The shutter pops and pops and with each pop comes a new yes or just like that and you can tell Coulter feels good.

“Let’s lose the hat,” commands her editor, Chris.

She obeys. And why shouldn’t she? This isn’t about Trump. This is about Ann. Could be a shoot for a pamphlet on Kelly Ayotte for all anyone cares. All this talk of Coulter at last finding her political savior? Please. He found her.

Take his infamous descent down the escalator of Trump Tower, the “Mexican rapists” line that launched a movement. “Where do you think he got that from?” Coulter, seated in her makeup chair, muses to no one in particular. It was her 2015 book, Adios, America!, of course, come to life. “He gave the Mexican-rapists speech,” she continues, her voice notched up an octave, “and life changed forever.”

Coulter, 54, has plenty of experience being known. She’s landed on the New York Times bestseller list 12 times. She’s sparred on cable news longer than you can remember. She’s had a talking doll made in her likeness. But 2016 is the year she became influential. 2016 is the year when the arguments that made Coulter rich—the ones that probably made you bristle, the ones you probably laughed off—transcended the vacuum of conservative media and attached themselves to a living, breathing major-party presidential nominee. “Perhaps no single writer,” wrote David Frum in The Atlantic, “has had such an immediate impact on a presidential election since Harriet Beecher Stowe.” And no one is more acutely aware of that fact than Coulter herself.

She spins out of her makeup chair, ready to photograph in bandage dress number two. “See? What have I told you all along?” she announces. “Coulter gets results!”

***

I first became a Coulter devotee in high school, when the ambient noise of Fox News around the house began to register some meaning. I started to sit down and listen to these people—Sean Hannity, Kimberly Guilfoyle, Bill O’Reilly. But I liked Coulter best. I liked the way she ran her fingers through her hair while she talked on air, a compelling show of femininity in what was so obviously a boys’ club. I liked that she was punchy and whip-smart and that no one dared talk over her. I decided around then—11th grade, I think it was—that there were few things I wanted more than long hair and an ability to argue about politics.

I went to college two years later and joined my school’s storied political union, which is perhaps only storied insofar as it is 82 years old. In truth it is a dreadfully self-righteous and self-indulgent and self-everything place, which I suppose worked well for my freshman-year self, a girl with long hair and a breathtaking confidence in her ability to argue about politics.

Coulter came to speak to the political union sometime in October. I don’t remember what about, only that I couldn’t sleep the night before. I was the first person to show up to William L. Harkness Hall, a cavernous, sepia-toned space whose every inch had already been canvassed by her security detail. I sat down in the fifth or six row, gold notebook ready, drumming my pen against my knees. The political union’s president walked in a few moments later. I think it was largely out of awkwardness—two people sitting silently in a room built for 100—that he invited me to the small meet-and-greet with Coulter before her speech.

So there we were, the ten lucky lottery winners and I, waiting in a small basement classroom for a chance to shake her hand. I cried—yes, cried!—as soon as I saw the golden shock of hair through the door’s window. That meeting would remain the hallmark of my freshman year—she gave me her email address! She followed me on Twitter!—and I remember it, as Joan Didion once wrote, with a clarity that makes the nerves in the back of my neck constrict.

My point, of course, is unoriginal. Idols lose their luster, and at some point we grow up and the curtain is jerked back and we wonder whether they changed or we did. What I mean to say is that Ann Coulter was once inextricably tied to my vision of conservatism and the Republican Party. And when those two institutions broke down this year, with the advent of a nominee who seems devoted to neither, I was jarred to see Coulter proudly tout her role in the crackup.

I shouldn’t have been shocked, but I was. I don’t have a great answer as to what changed my mind. Though I can remember every detail of times I’ve listened to and watched Coulter in the last several years—sitting on the couch watching Fox News after school, staring up at her behind a podium in that college auditorium—I don’t have the faintest idea of what she said. It was never about what she said, after all. It was about the hair, the dresses, the rhetorical shutdowns. But when there’s a Republican presidential nominee amplifying her words, and to such frightening influence, those gaps in memory vex me. Did I really just never listen?

***

Coulter is on top of the world. Between outfit changes, she says her past professional successes pale in comparison to this banner of a year, when people (meaning Trump) “finally started listening” to her.

Indeed, it’s one thing to claim one million Twitter followers; it’s entirely another to see your ideas, as translated through a presidential candidate, help capture the most Republican primary votes in history.

Coulter’s influence has largely been buoyed by the “alt-right,” the polite umbrella term for folks who might at one point be referred to simply as white nationalists, or anti-Semites, or neo-Nazis. They’ve occupied a privileged space this election cycle as Trump’s loyal warriors. Yet as many Republicans attempt to distance themselves from the alt-right while squaring their support for Trump, Coulter has embraced her queen-bee status. For the release of In Trump We Trust, she was feted at the headquarters of Breitbart, a publication tied tightly to both the alt-right and the Trump campaign.

Fringe sentiments themselves are not new—the John Birch Society saw the Civil Rights Movement as a communist plot, and Samuel Francis urged whites to reassert their racial solidarity in the 1990s. But movement conservatives such as William F. Buckley had largely succeeded in excising the influence of such figures, casting their conspiratorial and race-baiting appeals as antithetical to an intellectually and morally sound GOP. In 2016, though, Trump flipped the script, serving as the 21st century’s first large-scale vehicle for the alt-right and its sympathies. The misfit toys became the martyrs, and few understood that market better than Coulter.

Coulter’s career took off in the late ’90s, when she published the bestselling High Crimes and Misdemeanors and became a star voice in the case for Bill Clinton’s impeachment. Since then, she’s written 11 New York Times bestsellers, appeared on the cover of TIME as “Ms. Right,” and enjoyed plum speaking roles at high-profile conservative gatherings such as CPAC. Along the way, she’s occasionally clashed with others on the right: National Review cut her syndicated column in 2001, following her post-9/11 remark that “We should invade their countries, kill their leaders, and convert them to Christianity.”

Coulter, as the kind of person who makes a living saying such things, was born for 2016. She’s tweeted that Trump should “deport” South Carolina governor Nikki Haley, an Indian-American who was born in South Carolina. Following Khizr Khan’s speech at the Democratic National Convention, she called Khan—an American citizen whose son died in the Iraq War—“an angry Muslim with a thick accent” and later a “snarling Muslim.”

All of which is to say that the backlash against Coulter has never been greater among conservatives, or at least those who claim heir to Buckley’s teachings. But in 2016, for presidential hopefuls and pundits alike, support from conservatives could not matter less.

Three dresses and as many hours later, we’re in an Uber pulling up to Comedy Cellar, a famous stand-up spot and familiar haunt of Coulter’s. We rush downstairs and make it to our seats with just a few minutes to spare.

Before the lights dim, I ask what she will do if Trump loses, and her response seems practiced.

“First a cookbook, then mystery novels,” she says. “If Trump loses, the country becomes California. Politics are over for me.” She lowers her voice to a whisper, because the show is now starting. “I feel like an insect that gives birth and then dies.”

***

Coulter is more popular than any comedian here.

Take a seat at our table, where we’ve gathered post-show with some of her friends and an ex-boyfriend and her armed bodyguard (he started tagging along after the University of Arizona pie incident). The music is loud and the wine is plenty and Good God, someone yells, is that Judd Apatow? Taking a selfie with Ann?

She floats back to us. “I’m a fan,” she says breathlessly. “He told the Times he would want me to be the one who writes his biography.” (He did, in fact.)

The table is hardly large enough for her New York crew, never mind the rubberneckers. Even the waiters linger.

Over the next few hours she tells me about her “friend, Peter” (Thiel—“my biggest hero other than Trump,” she says) and why she’s never married (“They just never felt right in the end,” she says of her “definitely two, maybe three” engagements. “If I had married I would not be as happy as I am right now. I still make out with boys, though”). We talk about her mother, who passed away eight years ago. All the trips to Sloan Kettering. We talk about how some of the nastier criticism has never bothered Coulter personally, but it did hurt her mother, which brought its own set of pain.

It’s nearly 1 in the morning, and in this dimly lit room and under the cloud of noise I am once more the girl in the small basement classroom, entranced by the long hair, the easy confidence. Politics feel far away—it is just a shtick for her, after all, right?—and in that moment I sink into the long-ago dream of being Ann Coulter’s friend, talking about mothers and marriage and New York.

She hears someone across the table mention Trump.

Yeah, but the Judge Curiel thing, goes the conversation, I don’t think he should have said those things…

“Uh, no. No,” Coulter interjects, rising a few inches out of her seat. She leans onto her elbows, and with the force of whiplash the spell is broken. She’s back in character, the ringmaster directing her circus.

It just seems like it distracted…

“We have just spent ten months of the media saying, ‘All Mexicans hate Trump because he wants to build a wall,’” Coulter responds. “And then Trump says, ‘One Mexican hates me because I’m going to build a wall.’ And then, ‘Oh! Racist! Racist!’”

Just look at the African American vote! No one, she says, was more excited by the “Mexican judge attacks” than African Americans. “Blacks hate Mexicans…Mexicans move in and shoot black people, the jobs have been taken. Anything he says about Mexicans, his vote goes up with the brothers.”

She then whips out the “Make America Great Again” hat, apparently in her purse the whole night, and places it on her head. “It’ll never be this fun again!” she beams. And I realize, as I should have so very long ago, that the joke is on me.