On January 20, while Donald Trump is being sworn in a few blocks up Pennsylvania Avenue, movers will finish carting the Obamas’ possessions out of the White House. The family won’t be going far: The Kalorama Tudor where Barack Obama will begin his retirement is only two miles away. In sticking around while his younger daughter finishes high school, he’ll be the first chief executive in 96 years to remain in the capital.

Nostalgia will eventually set in, especially among Obama fans unhappy about his successor and inclined to see any change as a step away from a golden era. Which makes it a good time to reflect on the question of how the 44th President and his family shaped the city where they’ll soon be private citizens. Not vis-à-vis the grand themes of national and global history—the Affordable Care Act, Syria, same-sex marriage—but the folkways of the nation’s capital, the hometown and company town.

There was a time when the answer to that question seemed as if it might be momentous. When Obama took office in the panic-stricken winter of 2009, he was cast as a guy who might alter the trajectory of not just the country but Washington itself. In making government sexy and in quelling partisan rancor, he’d draw energetic newcomers to the region’s biggest industry. In the process, he’d lure a new population whose tastes, values, and residential choices would shape local life. It didn’t hurt that the Obamas looked the part: a young, cosmopolitan couple whose big-city background was strikingly different from the Clintons of Little Rock or the Bushes of Crawford.

Looking back on the last eight years, it seems pretty clear that the major trends that have shaped the way Washington lives, works, and plays—from the gentrification transforming the District’s demographics to omnipresent social media, recasting the way people in and out of politics socialize—were well under way before 2008 and would have continued no matter who won that year.

Yet it’s not exactly right to say our city would be the same were these the waning days of a John McCain presidency. The Obamas have altered Washington in some ways that might have been predicted and in others that might not have.

Here’s a first draft of the 44th President’s local history.

***

In June 2009, less than six months into his presidency, Barack Obama took a phone call with Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Obama leaned back and propped his feet on his desk, phone cradled against his shoulder. The White House photographer captured the moment.

Observers of the Middle East—where showing the soles of your feet can be an insult—might have predicted what happened next: a minor diplomatic incident, a perceived snub. But not until recently did a top official, punditing about the strained relationship between the leaders, suggest how such a gaffe could have been committed: The photo, it was suggested, had been okayed by young staffers eager to show how hip and casual the new boss was.

It’s an explanation that squares with anyone who was around workaday Washington in Obama’s first year. The President had promised to “make government cool.” More important, he had pushed through an $800-billion stimulus package. The local economy stayed buoyant, and recent college graduates who might have joined Wall Street were venturing here instead.

As the city brimmed with twentysomethings, the federal government seemed poised to benefit. But the numbers tell a different story. At the end of the Obama era, the number of workers under age 30 is at its lowest level in a decade, having dropped 34 percentage points between 2010 and 2015. By contrast, the number of workers under 30 increased each year of the George W. Bush administration.

Sequestration, which kicked in in 2013, was one factor, but even so, “there’s simply been less hiring in this administration,” says Max Stier of the Partnership for Public Service. What concentrated outreach efforts there were didn’t target millennials. In 2009, the Obama administration announced the start of an aggressive push to hire veterans; by 2015, 47.4 percent of new hires were vets, an increase of more than 23 percentage points from 2009.

For all the casual-Friday ease of Obama’s inner circle—the President had castigated the civil service’s “19th century” rhythms—federal employment remained a vastly less enticing opportunity for young people than one they’d find in Silicon Valley or a young-and-tech-friendly city like Austin, starting with a hiring model that Stier says favored “experience over capability.” (The administration scrapped the Federal Career Intern Program after an agency board ruled that it violated veterans’-preference laws.)

By contrast, career federal workers remember a positive mood shift in the broader sense of just who was welcome. “For me personally, being African-American and being able to rise in the ranks and become an executive [in the last eight years] is just—wow,” says Rachel Torres, an administrator in the Labor Department who has worked in the civil service for 24 years. She cites her department’s institution of a diversity-inclusion council as a “deliberate step” in recruiting diverse employees: “People who look like me have been able to become role models.”

That’s the sort of intangible that numbers can’t quite capture. Previous administrations have pushed for diversity, too, but over the last eight years—the White House now has a gender-neutral bathroom—the symbolism has rubbed off on people who will still be drawing a federal paycheck come January 21.

***

The biggest official-Washington workplace change of the Obama years—or at least the one that was foretold—hit people in an even older line of work than bureaucracy: influence.

Among his first executive orders, Obama banned lobbyists who had pressed on a particular issue in the previous two years from working in the administration on that issue—one of the most sweeping government ethics reforms in decades.

“I sort of knew the President had taken on the company town in a real way at the end of that first year,” says Norm Eisen, the adviser who helped draft the rule. “My wife and I got a lot fewer invitations to holiday parties.”

As it turned out, however, the order’s effect didn’t end influence-peddling as we know it—it just pasted a new facade onto an old game.

Lobbyists stopped calling themselves lobbyists—they “deregistered,” in industry jargon, downsizing to less than 20 percent the amount of time they spent facilitating meetings between a corporate client and officeholders, and upping their time spent “consulting for” and “educating” that client. According to American University government professor James Thurber, who tracks the industry, there were 2,905 fewer lobbyists registered in DC in 2016 compared with 2009. Suddenly, working as a “strategic adviser” never sounded better—something one prominent Democratic lobbyist refers to as a “self-reclassification of people in Washington” that ultimately led to less transparency, not more.

“At one point, lobbyists were eager to register and show off how many clients we had, how big our portfolio was,” says the lobbyist, who requested anonymity to speak candidly. “But nobody wanted that mark anymore.”

Case in point: Steve Ricchetti, Vice President Joe Biden’s chief of staff. At the end of 2008, Ricchetti—whose lobbying clients included AT&T and the American Bankers Association—deregistered. So when Biden tapped him in 2012, Ricchetti didn’t need a special waiver. He was unregistered, yes, but he was still president of his firm, where he had made $1.8 million the year before. The revolving door was still spinning, and by 2014, according to a Politico analysis, the White House had hired more than 70 staffers who had once been registered lobbyists.

“It’s clear at this point it was a branding exercise,” says lawyer/lobbyist Jack Quinn. “I was always able to present my case to people in government. I haven’t had difficulty in the last eight years in making sure that my clients are represented. It was still business as usual.”

Also unchanged was the background music of professional politics: relentless, relentless partisan warfare. Obama’s signature initiative, the health-care law, passed with zero support from the other party. This was, in a sense, part of the same trend line through the Bill Clinton administration—with its investigations and its impeachment—and on through the late years of George W. Bush. But in Obama’s case, coming on the heels of a campaign that promised to transcend calcified divisions, the persistence of the cold war felt especially bitter.

While that polarization is a national story, it was salient at the local level. The warriors of the 1990s might at least have had fleeting memories of cross-party socializing in the 1970s. No more. “The ideological sorting of the country and in Congress is reflected in Washington now,” says lobbyist and former GOP congressman Vin Weber.

Washington has traditionally been a place where liberals and conservatives have an easier time coexisting than they do at, say, the average middle-American Thanksgiving table. But gatherings among Washingtonians from either side, once a regular 5 pm sight, now feel more manufactured. “In the think-tank world, you might see mixed groups of people—they’ve worked hard to do that,” says Weber, who is on the board of the Aspen Institute. “Outside of that, it’s rare, like pulling teeth.”

***

Obama staffers had their own take on socializing. On January 19, 2013, Eric Lesser, Jake Levine, Josh Lipsky, and Herbie Ziskend threw what they called a third inaugural bash for President Martin Van Buren and Vice President Dick Mentor Johnson. “Oh, and while we’re at it,” the invitation read, “let’s toast the re-election of President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden.”

It was a homecoming of sorts for four bright young things of Obama’s first term, by this time in their late twenties and working elsewhere. Their Logan Circle rowhouse, stuffed with Ikea card tables and mismatched dishware, had once been the backdrop for parties peopled by White House staff assistants and top brass alike. On this night, the venue was different—the rooftop of Tabaq Bistro on U Street, since closed—but the guest list wasn’t. There was a cash bar and no food, and yet, look—there was Ben Rhodes, the President’s national-security communications deputy, working the room. Health-care-reform communications chief Linda Douglass, too.

The party was the kind of scene that would have been hard to imagine even ten years before—a bunch of current and former aides of all ages mixing in an edgy joint on Inauguration Eve—but it crystallized the preferred social rhythms of Obamaworld.

“I think the younger guard rubbed off on the old guard,” says Ziskend. “When you’re all on the campaign trail together, that happens.”

Washington has always had its share of preternaturally young aides—think George Stephanopoulos, barely 30 during his stint in Bill Clinton’s administration—but the strivers around Obama had little romanticism about old Washington. Invitations arrived “constantly,” even for the younger aides, says Lesser. “We’d come home and there’d be all these invitations from different ambassadors, for different embassy dinners, and sometimes we’d have to Google who the people even were.” (That’s not to say they didn’t accept some of them—just that they, as Ziskend puts it, “didn’t really like” them.)

No surprise, then, that on the other side of town, things were much quieter. “Socially, DC has taken an Ambien,” says Washington Post veteran Sally Quinn, whose Georgetown dinners were a focal point of elite socializing a generation back. The crew at Tabaq wouldn’t necessarily have been her guests—but, following the lead of their bosses, they might have wanted to be.

We’d come home and there’d be all these invitations from different ambassadors, for different embassy dinners, and sometimes we’d have to Google who the people even were.

Nowadays, there’s no more “scratching and clawing” to make the scene, Quinn says. “A lot of us tried to make friends with people in the administration. But more often than not, they just didn’t come. I don’t want to name names or get into that, but you’d have to go back at them a couple of times, and if they answered, then they would usually regret.”

“You have to remember that we were the insurgents and the mainstream was with Hillary,” Norm Eisen says. “We were never associated with the old guard, even us older ones, and we didn’t want to start just because we were now in the White House.” Eisen, for his part, says he and his colleagues would eat “mess-hall meals” and fro-yo after work while sitting on the steps of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building.

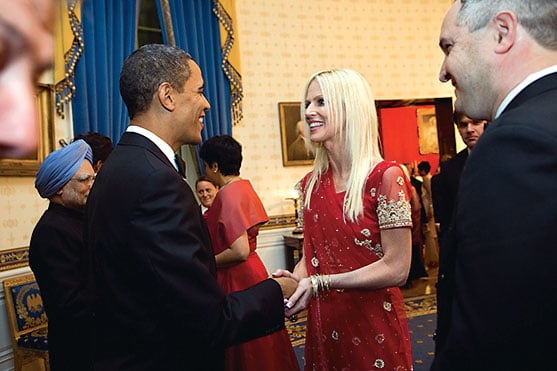

They also saw how people who cut a different profile suffered for it. Take Desirée Rogers, the administration’s first social secretary: Her departure was abruptly announced on a Friday in 2010, a few months after the infamous state dinner for India’s prime minister, where Rogers, off enjoying the party inside, inadvertently allowed an uninvited couple, Tareq and Michaele Salahi, to trot through the doors.

It’s not that the Obamas weren’t plenty comfortable clinking glasses with high-wattage types. They were, after all, the First Couple who liked to invite Beyoncé and Ellen DeGeneres to town for private parties. It’s just that they preferred to socialize more with celebrities from outside the Beltway, not the ones you’d read about in Playbook.

***

On May 21, 2016, Michelle Obama joined 11 friends for dinner at Ottoman Taverna, a new Turkish restaurant in Mount Vernon Triangle. Afterward, the city’s food scribes dashed off a few obligatory lines. (The big takeaway of the outing: She wore all black.)

By this point in the administration, it wasn’t news that the First Lady was spotted enjoying a voguish restaurant or gym. She has dined at more than 50 restaurants in the past eight years, including three times at Masseria, whose on-the-fringes-of–Union Market locale doesn’t fit most conceptions of presidential pomp.

For Washingtonians, the Obamas’ propensity for nontraditional outings mattered more than the (diminishing) thrill of seeing the First Family in one’s neighborhood. If elite insider socializing had become snoozier, the city at large was vibrant, its culinary scene experiencing a renaissance—and, for the first time in a long time, the President was associating himself with that mood.

Why? For the Obamas, hailing from a city where the food scene had been rich long before Washington’s, there was probably nothing particularly intentional about their outings—they and their Chicago-transplanted staff alike had always been tied to that kind of lifestyle and would stick to it here as much as could be reasonably expected. “They’re just acting as couples and parents their age would,” says veteran New York Times food columnist Marian Burros.

All the same, business owners were thankful for the attention. “I think that there’s no way the restaurant industry would have seen the same level of energy and enthusiasm had McCain been President,” says Constantine Stavropoulos, owner of the restaurants Open City, Tryst, and the Coupe. “Obama created a spark. I mean, it’s true that with every new administration, there’s a bump, especially at the beginning. But this was a mountain.”

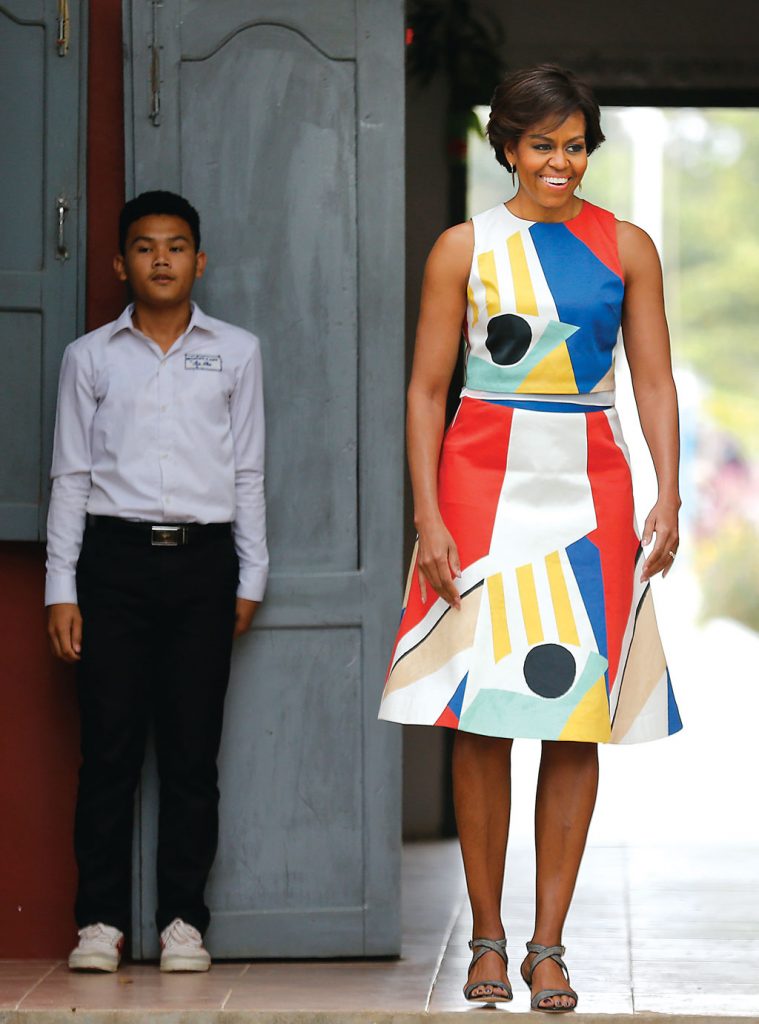

Michelle Obama’s style—from clothing to gym preferences—became influential, too. Of course, First Ladies dating back to the founding of the Republic have shaped public opinion in fashion, but not always in ways that felt accessible. In Obama’s case, her choices actually flattered the new Washington’s sense of itself. “I started to see a growth in the market from a style perspective close to the moment the Obamas arrived—edgier brands were in much higher demand,” says Aba Kwawu, president of the public-relations firm TAA PR. “I’ve been here 15 years, and DC wasn’t necessarily respected in the fashion world, because we didn’t want to be known for style—it was about being smart and well traveled. That’s still the culture to some degree, but Mrs. Obama made it acceptable to care about style alongside everything else.”

Like the young aides who opted to dine out rather than attend insider dinners, the Obamas were around—with their daughters at Sidwell, going to basketball games and concerts, on an outing to Politics and Prose around the holidays, ducking into SoulCycle. In the history of US presidencies, that alone was noteworthy.

***

Indeed, This First Family seemed to go everywhere—and as each corner of the city transformed itself into something of a destination, there was little reason not to. “This is a guy who wasn’t afraid to pioneer new neighborhoods regularly,” says developer Jim Abdo. “I think in that sense the idea of ‘power corridors’ dissolved.”

While previous administrations had associations with some particular neighborhood—think of the New Dealers in their Georgetown haunts—a striking thing about the Obama generation was how much of the city seemed to be their stomping grounds.

But to a swath of Washington, it was just as striking to see how the places the Obamas went in their free time had limits. “He was out at the fancy restaurants, yes,” says Maurice Jackson, an associate professor of history and African-American studies at Georgetown, “but you have to understand that those aren’t out in the black communities.”

When Obama took office, DC was still “Chocolate City.” Three years into his first term, that was no longer the case. In 2012, the District’s African-American population dipped below the majority mark and fell to 49.5 percent—from a high of 71 percent in 1970. By 2015, it would drop further, to 47.4 percent.

The trend lines were in place well before the nation’s first black President arrived. But one of the unintended byproducts of his administration—which helped keep the city afloat in 2009 and advertised its emergence as a creative-class destination thereafter—was probably to hasten the city’s gentrification. That’s why, for Jackson, DC’s growing whiteness made Obama’s engagement with its black residents, or lack thereof, all the more symbolic.

“You saw an influx of young white people in the last ten years who had no appreciation for the struggle of African-Americans,” he says. “As the city became so greatly gentrified . . . that was the time for Obama to make more gestures.”

Jackson would have liked to see Obama reach out to the city’s black communities in more personal, unceremonious ways, particularly as the city was filled with “African-Americans—especially young men—who just wanted to be seen with him.” He credits the President for delivering a commencement address at Howard University this year but says that gestures such as attending a football game between Dunbar and Coolidge high schools, taking a stroll through Anacostia, or attending a historically black church more often “would have gone a long way—that’s how you engage the black community.” (To the fury of DC-statehood activists, Obama negotiated with John Boehner to undercut some home-rule prerogatives, the kind of federal big-footing that was once cast as a civil-rights issue.)

It does disappoint me. I think we expected a lot out of him with respect to the black agenda. He’s done as well as he probably could, but it’s true that he was not visible in the places that people needed him the most.

Talk to Jimmy Garvin, manager at the Langston Golf Course in Northeast DC and the regrets about Obama’s legacy in the District are practically palpable. Back in 2009, Garvin told ESPN that the course, once the only place African-Americans could play in the area, would inevitably get its first presidential visit. Eight years and 321 presidential rounds of golf later—according to CBS White House correspondent Mark Knoller’s tally—Garvin is still waiting.

“It does disappoint me,” he says. “I think we expected a lot out of him with respect to the black agenda. He’s done as well as he probably could, but it’s true that he was not visible in the places that people needed him the most.”

***

DC in the last days of the Obamas is richer, younger, and whiter than before the First Family arrived. Plenty of people will tell you it’s cooler. But just as many will say the District has never felt more like two different cities at once.

Both are true.

When it comes to how we live, and how we play, the District has a new gloss. Yet we’re as steeped as ever in the same challenges as before, from mundane ones like improving federal hiring to tragic ones like racial inequality.

It was inevitable, even eight years after the Obamas marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in front of historic, ecstatic inaugural crowds, that no mere President could knit a social fabric together nationally. Same goes at the local level: The notable thing is that many Washingtonians—for all our talk about how we’re a city much bigger than the government—believed Obama could. Which may wind up being the thing people most remember when they look back.

Herbie Ziskend recalls, in a moment of “naive curiosity,” asking the late Washington Post journalist David Broder what had changed most in DC since he first arrived in the 1950s. Broder paused for a moment, then replied, “The television.”

Says Ziskend: “It was a good reminder that, yeah, we were these idealistic foot soldiers who wanted to change the world, but we weren’t the first ones. Obama wasn’t the first President, and not the last, either. But it was fun to think so.”

This article appears in the December 2016 issue of Washingtonian.