When Jim Vance died in July, the city’s response was immediate and heartfelt, stretching across boundaries of race, income, and neighborhood. It was also, most likely, the last of its kind. Washingtonians will never again mourn a TV news personality the way they grieved for the NBC4 anchor.

In part that’s because the audience for local TV news keeps shrinking and aging, but it’s also because the Washington where Vance worked for more than 45 years no longer exists. This region was a Podunk with 2.7 million people when he moved here in the late ’60s; now it holds more than 6 million, and by 2030 we’re projected to add 1.5 million more. In this sprawling, global region—as in our sprawling, globalized media environment—it’s hard to imagine a mere local-news anchor breaking through to stardom.

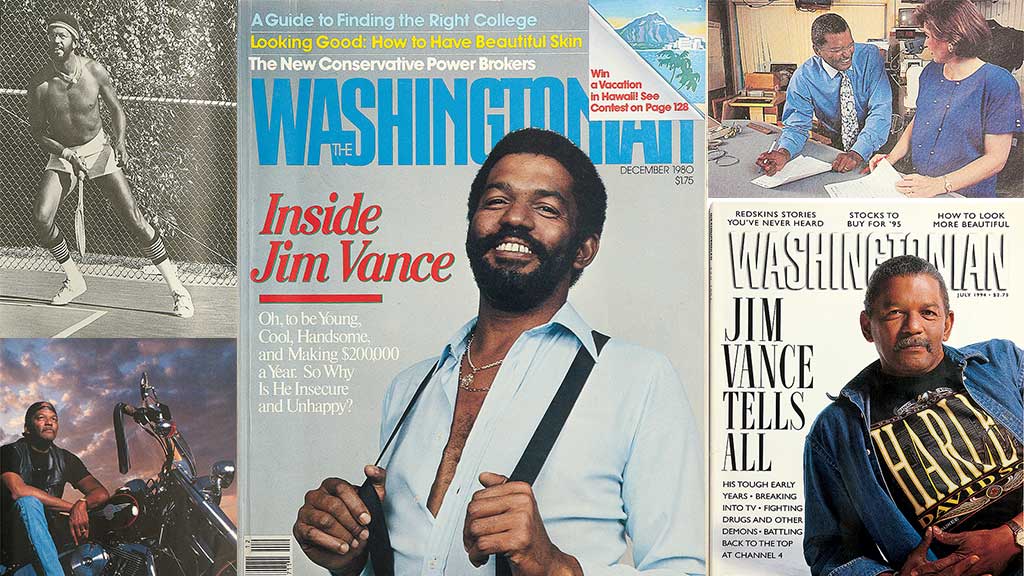

Not so long ago, it was different. Vance mapped his fame to a metropolitan area where publications such as this one breathlessly reported his salary ($200,000 in 1980) and ran photos of him enjoying his downtime—driving his Porsche, fishing, playing tennis shirtless and wearing a headband, white short shorts, white Nikes, and socks pulled up to his calves. His longevity behind the anchor desk was a comfort to people moving in and out of the area.

But just because his rise coincided with the era of Ron Burgundy doesn’t mean Vance wasn’t the author of his own fame. Yes, he was a skilled newsman whose life was dramatic. Yet there are plenty of skilled journalists and plenty of people whose personal crises play out in public, as his did. In a city rich with ambitious former student-council presidents, Vance also appealed to Washingtonians in the way he appeared not to give a rhymes-with-duck.

“When managers and news consultants told him to play it safe, he pushed the envelope,” Vance’s friend Arch Campbell wrote for Washingtonian. “When they told him to cut his hair, he grew an Afro. When they told him to shave his mustache, he added a beard.”

Vance certainly had a lot in common with DC’s ascendant African-American middle class. He came from a working-class family in Philadelphia and remembered his dad crying because a plumber’s union wouldn’t let him join. Vance came here from WKBS in Philadelphia after the ’67 riots in Newark and Detroit convinced TV stations they needed to diversify their staffs. He displaced his idol Neil Boggs and joined what was charmingly called a “salt-and-pepper” anchor team with Glenn Rinker. Vance outlasted partner after partner—Rinker, Jackson Bain, Jim Hartz, Sue Simmons, Marty Levin, Dave Marash—before Doreen Gentzler arrived in 1989 and stuck.

Gentzler joined what was at that point an established team, usually number two in a fractious market balkanized among Gordon Peterson and Maureen Bunyan on Channel 9; Renee Poussaint and David Schoumacher on Channel 7; and Vance, George Michael, Bob Ryan, and Campbell on 4. But it was the Channel 4 team that made the most progress into national culture—Michael with his “Sports Machine,” Campbell via a brutal Patton Oswalt routine (he and the comedian are now friends), and Vance in the most improbable way of all: The band Foo Fighters, fronted by Springfield native Dave Grohl, made a video tribute to the anchor when he stepped down from the 11 o’clock news in 2015.

Little about that video would be even slightly comprehensible to anyone under 40—references to the Roadducks, the Ultimate Warrior, and the Bottle & Cork, not to mention Vance’s viral crackup when a model fell on a Paris runway. But that made it even more authentic: If you grow up in this area, it’s common to define yourself by the fact that you’re not some dweeb blowing through with whatever administration or ideas are in power. Local anchors, by definition, aren’t known to the newcomers from Kansas City or Birmingham.

We recognized that thirst for authenticity in Vance, a guy who complained publicly about TV fashions such as “cross-talk,” who said, “This business is nowhere near the fun that it used to be,” who griped about having to cover Snooki. Just as his viewers liked to think about themselves, he was a guy who told it like it was in commentaries, then headed out to fish with the President or to crush some rural roads in Virginia on his Harley.

Despite all his badassery, I think Vance actually represented something deeper, something that resounded in a region full of strivers—the fear that you’re a fraud, that you have no right to have risen as far as you have.

“Fact is, man, my shit is pretty jive,” he told Washingtonian in 1980. “I guess my real problem is that I’m not sure this anchoring deal is what I’m here for.” Fourteen years later, he said he didn’t “expect to be celebrating my 50th anniversary at [Channel 4]. Or my 40th. Or my 35th.”

Anyone who’s dealt with similar feelings, or known someone who had them, will tell you they express themselves in ways that seem to make no sense, such as Vance’s devastating cocaine addiction, which nearly cost him his career and his family in the ’80s. After he relapsed following a stint at Betty Ford, he found himself living alone without a car, with a broken motorcycle, riding the bus and hoping no one would recognize him. “My self-esteem has always been so incredibly low,” Vance told Gentzler in a 2015 interview when he opened up about the depression he’d suffered for much of his life.

After he relapsed, the city’s best-known newsman was living alone, without a car, riding the bus and hoping no one would recognize him.

He got clean, and his career recovered. That glorious Channel 4 team you used to see on bus ads disintegrated, victims of corporate cost-cutting. Campbell left in 2006. Michael said goodbye in 2007 and died two years later. Ryan left in 2010. Vance settled into the role of dean of Washington broadcasters, mentoring younger employees—especially African-American ones—at Channel 4, attending the endless award shows and fundraisers that are as important a part of anchoring as time onscreen, and remaining one of the most recognizable people in town. (“Yeah, I know this guy,” President Obama said when Vance sat down to interview him.)

Nowadays, Jim Handly, who took over the 11 o’clock news from Vance, is liable to eat dinner in peace—national broadcasters such as Jake Tapper are more likely to be harassed when they’re out and about. News isn’t something we make an appointment to watch any longer; it’s practically ambient. When the local anchors of today move on to the next realm, they’ll probably get a few nods of recognition, if they’re lucky. Vance will stay with a few generations of Washingtonians for a while, his legacy sneaking into their consciousness when they hear MFSB’s “My Mood” at the end of the Friday 6 pm news on NBC4, for instance.

Vance suggested that track back in 1975, and it has outlasted all the consultants and managers who tried to kill it—the languid groove, laid down by the studio musicians behind so many Philly soul records, signaling what used to be the end of the workweek. Vincent Montana Jr.’s vibes and Don Renaldo’s strings and horns are simultaneously cheesy and uplifting. It sounds dated, but it still grooves.

This article appears in the September 2017 issue of Washingtonian.