He was responsible for creating the villainous "Joker" and "Robin the Boy Wonder" in Bob Kane's 1940s Batman comic book series (Kane convinced him to leave an average job selling ice cream) and worked for years as a syndicated political cartoonist. Now 85 and not losing steam, legendary comic book figure Jerry Robinson has produced his first musical with friend and colleague Sidra Rausch, co-founder of Washington Women in Theatre.

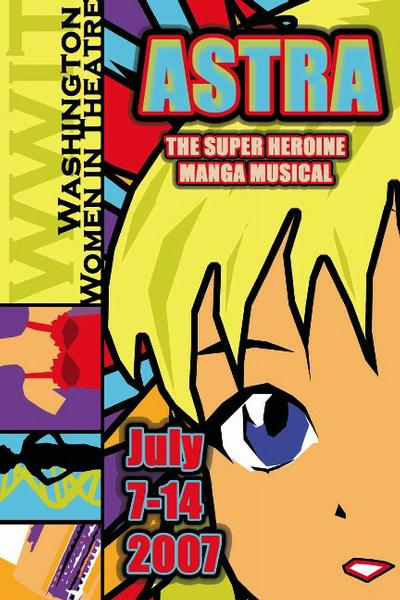

Astra: The Super Heroine Manga Musical stars a princess from the planet Eros sent to Earth to save her all-female colony from extinction. How will she succeed? Finding a male Earthling to settle down with and begin future generations of Eros inhabitants. The time period? The late 1980s and early ’90s, at the tail end of the Cold War.

I chatted with Robinson to learn more about the musical, which debuts in Washington on July 7 at the Warehouse Theater (1017-1021 Seventh St., NW; 202-783-3933).

Where did the inspiration for Astra originate? The same creative juices responsible for the Joker?

I was giving a talk about Batman on Cape Cod—I think it was the late ’80s. Afterwards, Sidra Rausch came up to me—she would later become a dear friend—and said something like “How do you feel about feminism?” Very in-your-face question. From there, it became our summer project. We got absorbed writing the songs and script together.

So the story of Astra didn’t originate as a comic strip but as a musical?

Right. The musical takes the characters out of the comic-book realm completely. Only later did it become a manga hit in Japan.

What is a manga, for all the non-comic-book heads?

Manga is the Japanese word for comics. Their drawings are really idiosyncratic.

A Japanese artist saw my Astra drawings when I was holding my first retrospective show in Tokyo. The curators of the exhibit asked if I was working on anything at the time, and when I mentioned the musical, they said, “That’s great! We’ll add it to the show.” So I handed over some sketches, and months later a Japanese publisher was asking to meet with me. He wanted to license Astra as a manga. The publishing house then went on to publish six issues of the sequential narrative.

Is it common for Japanese manga artists to adapt American concepts like that?

Not at all. In fact, this was the first international collaboration on a Japanese manga. And to make this project even more international, an American publisher later saw the Japanese version and wanted to create his own version. It went back and forth between the countries.

Did it always hold onto the same Astra story at the core?

Well, the Japanese version had the original premise and the same name, plus all the main characters that Sidra and I created. Except they tweaked the images a bit—gave them a very erotic feel. It’s amazing how stuff is accepted over there for both children and adults. It’s almost borderline pornographic. I wasn’t so happy with this interpretation and had them let go of certain characteristics before the second issue.

Sounds like sensual images for the Japanese businessmen to fantasize over. I noticed the two completely different covers. One is blond and blue-eyed. Very promiscuous-looking. The other is altogether different. Much less like a vixen.

Exactly. The first was the original, which had the really erotic episodes. I didn’t want that for the American version. Especially since she’s supposed to be an empowered, modern-day female.

She really represents the modern woman. Astra sees the absurdities in our society as an outsider, especially in regard to the Cold War. It’s interesting for people to look at our world through her eyes—see both the wonderful and ridiculous issues on Earth.

She’s an outsider, but where does she come from? You mentioned Eros.

Planet Eros, yes, which after years of battling has no males left. The male population was wiped out, so the planet has saved one vial of sperm to procreate. Each year, Eros can impregnate only so many women. After years, the notion of man even becomes a myth. Women have no idea what men looked like at that point. Queen Astra is selected to birth the final daughter.

There’s a huge ceremony. But when she takes out the vial, it’s practically empty. Which means the last generation will be born. Once old enough, Princess Astra has to visit Earth to save Eros.

When she flies into orbit, an American lieutenant on a space mission notices her egg-shaped rocket. After finding her unconscious on the floor, all out of oxygen, he takes her to Earth, which is where the story starts to feel more real.

Real?

Well, just imagine somebody from space visiting Earth. There’s a grand White House reception. And since this is set during Cold War times, the East versus West issue is huge. The Russians want her for military info. So does American intelligence. The villain, Dr. Light, wants her for commercial purposes. Everyone wants a piece of Astra.

Why did you and Sidra decide on the Cold War setting?

This comes after my many years of political cartooning. I made a series called “Stereotypes” in the 1990s, which used all the typical propaganda of that time—Boris Yeltsin, the capitalist Americans. I worked with a famous artist, who is considered the Russian Disney, in his Moscow studios. Astra is a parody of how an outsider would witness all this. Part tongue in cheek, part romance. A political satire, like I said.

When Sidra and I first wrote the musical, this is what we wanted to epitomize. The depths of the Cold War, the American tensions with the USSR. And funny enough, now it’s all coming back again.

So it’s got the Japanese connection, the Russian connection . . .

Exactly.

Very international work. Will the show travel?

Oh, yeah. That’s definitely a goal. Some folks on the West Coast are even interested in adapting Astra into a film, either animated or live action. So after the show we’ll be concentrating on that, and touring like you said.

Does Washington have special significance for you, especially given your political-cartoonist history?

Sort of. Back when the Washington Post shared a microphone with another major paper, the Washington Star, my syndicated cartoon ran in the Star. At that time, I was in and out of Washington quite a bit, meeting with several presidents in the Oval Office, like LBJ and Carter. There was a fundraiser dinner with Truman once. All of them commissioned me for original Batman artwork.

Any standout memories of the White House?

Actually, yes. I was supposed to deliver a cartoon to Kissinger. Or Dr. Kissinger, as they called him. When I got to his office, his aide greeted me in Kissinger’s office, but no Kissinger. The aide wasted no time taking pictures with me and expressed his regrets about Kissinger’s absence. We sat down and he said, “I can tell you why Dr. Kissinger isn’t available. But if I tell you, you can’t leave this room for an hour and a half.” I thought, well, I have nothing else to do. Literally, I was a prisoner in his office. Later that afternoon, the White House press release came out that Kissinger was in Beijing for a very important meeting. [Laughs.] Good thing they didn’t let me go. I would have been tempted to rush immediately to the Star and tell them.

My memoir, which will be published by Abrams next year, also goes into this story.

Do you have any other plans while in Washington in July? Perhaps another hostage moment in the White House?

Astra actually overlaps with the American Association of Editorial Cartoonists national convention. As a past president, I always go, and about every four years we meet in Washington. A bunch of us political cartoonists will meet on July 4 weekend—political satirist Will Durst; Ann Telnaes, the second woman to win a Pulitzer for her editorial cartooning; Jeff Danziger, who’s a big one at the Christian Science Monitor and perhaps the most outspoken American cartoonist on the Iraq War. We also hold fundraisers, raising money to fight for cartoonists’ rights around the world. Usually the President is invited, too. [Laughs.] But that probably won’t be the case this year.

Last question: Should we look for any subtle references to the Joker, or Batman buried in Astra?

[Laughs.] No subtle references. You’ll have to make those associations yourself. Dr. Light is the villain, a global Internet mogul trying to control the world by hacking into computers. But he’s definitely not as bizarre as the Joker.

There was a poll taken among critics and writers last year. I think it was in London. Hundreds were asked to name the most famous villain in all of literature, not just comics—everything from Sherlock Holmes to Dostoevsky. The Joker came in at number one. Hearing that was very meaningful for me. Really, a once-in-a-lifetime thing.

What an honor!

Yes, truly. I’ve been around the world to 43 countries in my career. But it’s amazing to see how everyone can know the Joker. Even a little village in Cuba once. The locals asked me to draw a mural of him. And of course I did.