It’s all about the N’s.

Ryan has one, as in Zimmerman.

Jordan has two; his last name is Zimmermann.

Ryan is from Virginia, Jordan from Wisconsin.

Ryan plays third base; Jordan pitches.

Ryan is an inch taller and two years older.

When he walks near the stands, Jordan often hears “Hey, Ryan, throw me the ball.” Or “Hey, Ryan, sign my program?”

The two Zimms met in spring training this season.

“It’s good to finally meet you,” Jordan said. “People keep asking if we’re brothers.”

“Yeah,” Ryan responded, “I get the same questions.”

One sunny afternoon before the Nats play the Pittsburgh Pirates, I ask Jordan if he looks up to Ryan like a big brother. He shakes his head.

“The whole team is extremely young,” he says. “It’s easy to get along with everyone. We’re all pretty new. We all talk the same language.”

The two Zimms do have things in common: They come from small-town America and made their marks playing sports; both are unassuming and hardworking; each still has the innocence and hopefulness that players sometimes lose after their first million-dollar season or second trade.

And in a woeful season for the Nationals—dubbed “the world’s most excruciating baseball team” by the Wall Street Journal—the two Zimms offer fans a chance to dream of a team that might become a winner.

“The Nationals are doing it the right way,” Ryan says. “They could have gone out and bought players who were good for a year or two. Instead, they drafted young players who can grow up and mature together. It’s good for the long term.”

In the short term, Jordan Zimmermann has begun his first major-league season with solid starts that sometimes turned into losses because his teammates failed to catch fly balls or score runs.

Take the May 27 game, when he faced New York Mets ace Johan Santana in the Mets’ new ballpark. Zimmermann had turned 23 four days earlier. He battled Santana to an even 3–3 through five innings, even though left fielder Josh Willingham missed a fly ball, catcher Wil Nieves muffed a pop-up, and second baseman Ronnie Belliard forgot to cover first on a bunt.

“It was fun up through the fifth,” Jordan says, “until the so-called home run.”

In the bottom of the sixth, New York’s Daniel Murphy launched a ball toward the right-field seats—it seemed to die and landed on the field in front of Nats right fielder Adam Dunn. He fired it to Belliard, who threw it to Nieves and nailed a runner at home plate. Umpires reviewed Murphy’s blast and said it had actually cleared the fence, hit a sign, and landed back on the field—and therefore was a home run.

Zimmermann was down 5–3. The Mets added two more runs, and Jordan took the loss for a 2–2 record.

Was he intimidated by the Big Apple crowd?

“Not at all,” he says with that flat Midwest tone that’s both laconic and assured.

Was he pleased with the game?

“I did pretty well for the most part.”

Coming up in the small town of Auburndale, Wisconsin, Jordan Zimmermann did very well at basketball.

“I always thought it would be basketball if I made it anywhere,” he tells me. “I never thought I would be a baseball player until I went to college.”

Auburndale is a village of some 750 people in the northern part of Wisconsin. Auburndale High has an annual Bring Your Tractor to School Day. Zimmermann played wide receiver and free safety on the football team.

“I also pitched,” he says. His fastball was clocked at 86 miles an hour.

Zimmermann is an only child. His father sells welding equipment; his mom is a secretary at a trucking company. He has lots of cousins, uncles, and aunts who all gather for holidays.

“I was spoiled my whole life,” he says.

His senior year in high school, he got recruitment letters from the University of Minnesota and the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. He chose Stevens Point, 25 miles east of Auburndale. “I wanted to be close to my buddies,” he says.

He stuck with baseball rather than football. He improved his speed. He started lifting weights. “I wasn’t pushing off the rubber,” he says. “I was using all arm. I started to use my abdomen.”

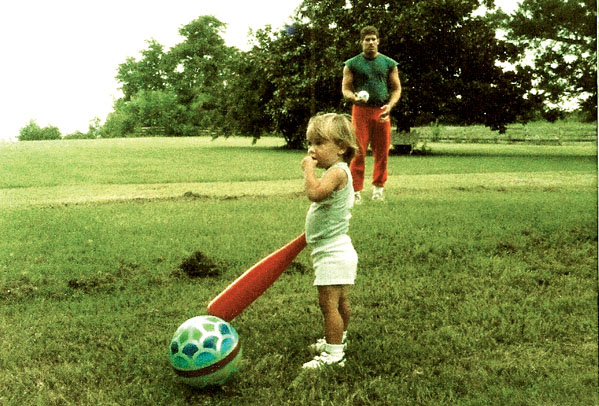

Ryan started whacking balls around the yard of his Virginia Beach home before he was two. Photograph courtesy of Zimmerman family.

His pitches reached 90 miles per hour. His earned-run average (ERA) was 2.3 his sophomore year. That summer, he pitched for the Eau Claire Express in the Northwoods League, which draws top college players. His ERA was 1.01. Major-league scouts started showing up with speed guns.

Nationals scout Steve Arnieri watched Jordan pitch during his junior year at Stevens Point. “I loved his stuff,” Arnieri says, “but I loved his makeup even more—his tenacity, his concentration, his steely-eyed determination. He attacked hitters—he was unafraid.”

Arnieri and Nats executive Mike Rizzo met with Zimmermann. “For about five minutes,” Jordan says.

That was enough for the team to choose him in the second round of the 2007 draft. Jordan accepted the offer, quit school at the end of his junior year, spent two years on Nationals minor-league teams, excelled in spring training, and this season joined the starting rotation.

Ryan Zimmerman also quit college his junior year to join the Nationals. He had grown up in Virginia Beach, had played baseball his whole life, and was attending the University of Virginia when the Nats beckoned in 2005. He spent a few months in the minors before the team brought him up to play third base, where he’s been anchoring the defense—and the offense—since the 2006 season.

Where Jordan is still mostly potential, Ryan is a star. In his first season, baseball columnists said he could become a Hall of Famer like Brooks Robinson. Now in his fourth season, he stops almost every ball hit to the hot corner; he throws across the diamond as if shooting the ball from a gun. I’ve seen him nail runners from deep behind the bag and from his knees in the dirt. His 30-game hitting streak led the major leagues. He’s a threat every time he steps to the plate.

When I profiled Zimmerman in July 2006 (“The Rookie”), he was sharing an apartment in Clarendon and living on a $400,000 salary. This spring, the Nationals signed him to a five-year contract for $45 million. He’s still living in the townhouse on Washington Boulevard in Clarendon that he bought after his rookie season.

“The money really hasn’t changed me or my lifestyle at all,” he says the afternoon before the Pirates game. “For my family, it’s knowing they won’t have to worry about money.”

His father has retired and can stay at home with Ryan’s mother, who has multiple sclerosis. His brother is finishing college at Radford.

Ryan, 25, looks leaner. He has worked out over the summer—kept his weight the same but added muscle. His face has lost the baby fat it had at age 21. His features are chiseled, his gaze is sharper, his focus on baseball seems total.

“No new car, no new house,” he says. “I’m a single guy. I already have a home and a decent TV room. I had everything I needed already.”

A steady girl?

“I date,” he says, “but I’m too busy for much else. There’s too much going on. I’m having too much fun to be locked up in a relationship right now.”

Jordan Zimmermann lives in the Hallstead apartment complex in Arlington with his girlfriend, Mandy Jellish. She graduated from Wisconsin–Stevens Point, found a job in the Washington area, and moved east.

What does a 23-year-old country boy yearn for?

“I would rather be surrounded by woods,” he says. “I would like to be hunting and fishing when I’m not playing ball.”

In Auburndale, he had to drive 20 minutes to see a movie; now theaters are a quick walk away.

“Here in the city, you have everything you want,” he says, “but you don’t get to do what you want.”

Like hunting white-tailed deer or fishing for salmon and walleye.

Zimmermann’s family and friends flew in from Wisconsin for his debut April 20 against the Atlanta Braves. High-school and college buddies joined his parents and aunts and uncles. “People I didn’t expect to come were there,” he says.

Late in the game, the heavens opened, emptying the stands and halting the game. When play resumed, Zimmermann looked up to see about 100 fans.

“Looked like half were from back home,” he says.

The kid won 3–2 and sent a happy crew back to the fields and woods of Wisconsin, where he often would rather be—except when he’s on the mound.

This article first appeared in the July 2009 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from that issue, click here.