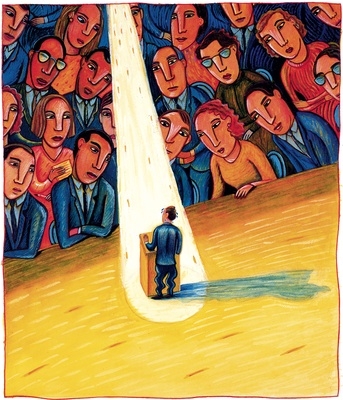

It’s that tremor in your fingertips as you make your way to the podium, your heart pounding with the realization that a roomful of people will be checking out your every word and movement.

The performance anxiety associated with public speaking is one of the most common phobias, and for some people it can be a barrier to career advancement. For them—as well as for those who just want a little more polish at the podium—taking a class or joining a speaking club can be helpful.

“It goes back to when we were in grade school and had to get up and give a three-minute talk about how to tie your shoelaces,” says Larry Parnell, a professor who leads public-speaking workshops at George Washington University’s Center for Excellence in Public Leadership. “People feel they’re being judged. And in a way, they probably are. People are sizing you up and saying this individual knows their subject and is able to communicate it to me well.”

Scott, a 33-year-old graphic designer who didn’t want his last name used, first froze with stage fright while giving a presentation in his college Spanish class. He has struggled ever since. Now he’s trying to conquer his fears in a class at Alexandria’s Stagefright Survival School.

“As I’ve been promoted, I’ve thought there’s going to come a time when I’m going to have to give a big presentation or a speech,” Scott says. “And when that time comes, I want to be ready.” It took only a few classes to start feeling more confident, and he’s no longer dreading the best-man toast he’ll give at a friend’s wedding.

On a recent Monday evening, Scott and his classmates took turns giving mock presentations. A woman recounted the alarm she felt when addressing guests at a dinner party she hosted. A man practiced a presentation he’d be giving during a business trip to Japan the following week—in Japanese.

Instructor Burton Rubin, an attorney and stage-fright sufferer himself, emphasizes slowing down, focusing on the physical environment, and accepting your anxiety instead of trying to fight it. That last technique helps his students focus on their speeches rather than on the self-conscious thoughts that trigger the release of anxiety-producing chemicals in the body.

“The way we’re wired up, you can’t distinguish between something that will harm you physically and something that will harm you socially,” Rubin says. “If you think that you can embarrass yourself, if you think that you can diminish yourself in the eyes of other people, these chemicals will be released just as if a tractor-trailer was coming over into your lane on the Beltway.”

In Larry Parnell’s “Step Up to the Microphone With Confidence” workshops at George Washington University, federal and local government employees analyze videos of effective speakers such as Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama and work on their own presentations, with a focus on how to speak in front of the media.

“They may have the technical knowledge that exceeds everyone around them, but if you’re not able to communicate that, then your career is really going to be limited by your inability to make your management or your colleagues understand what you’re trying to do,” Parnell says.

Nancy Eyl had gotten used to speaking in front of a group while she was teaching college-level Russian and German, but when she left the classroom for law school, her naturally shy tendencies resurfaced. In May, Eyl gave an “icebreaker” speech about the Office of Inspector General—where she works—during a lunch-hour meeting of Monumental Voices, one of more than 400 local chapters of the Toastmasters International speaking club. Toastmasters members give speeches that focus on such skills as vocal variation, body language, and using visual aids. They receive peer evaluations, practice extemporaneous speeches, and even designate one member to count others’ “ums” and “ahs.”

For Eyl, having to give a speech to the group has helped sharpen her skills. “The thing about public-speaking training,” she says, “is it increases your confidence because when you have more experience, you lose that fear. It’s a matter of getting practice.”

Tips from the Toastmasters arsenal include arriving early and familiarizing yourself with the room and any equipment you’ll be using. To curb the anxiety of addressing a roomful of strangers, introduce yourself to a few people as they enter. If you make a mistake, don’t draw attention to it by apologizing—just pause, collect your thoughts, take a deep breath, and pick up where you left off. People tend to speak too quickly when they get nervous, so Rubin suggests timing yourself reading aloud, then deliberately slowing your cadence. Practicing your presentation in front of a mirror, a pet, or family members can help make you feel more comfortable with the material.

Jeff Kudisch, managing director of the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business career services—who also works as an adviser to executive MBA students—recommends that people volunteer to read to groups of children at libraries where they can practice vocal variation, volume, and pacing in front of a less intimidating audience.

One of Kudisch’s former executive-MBA students was Kim Gifford. As Gifford found success in her career and was studying for her advanced degree, she discovered she felt intimidated giving presentations to her new colleagues and classmates. “When I got into this experience where I was surrounded by competitive, accomplished individuals, for the first time ever I struggled with some nervousness,” Gifford says.

Kudisch suggested in 2009 that she step outside her comfort zone at an improv class in Alexandria.

“When you’re in front of this group, you want to have the confidence to be the authority figure,” Gifford says. “The class helped me gain that confidence. It’s been very helpful over the last year to reflect back on drills or skits that we did and find ways to incorporate those concepts when I’m at a public-speaking event—how I can deliver a better message to my audience and maybe create a situation where they’ll be more receptive to hearing the message I want to put out.”

Gifford was promoted to executive director and CEO of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons in July.

In February, Kudisch brought his brother, Tony-nominated Broadway actor Marc Kudisch, to Maryland’s campus to lead MBA students and executive-MBA alumni in an improv workshop to help sharpen their presentation skills. Jeff Kudisch says the program was so successful that the school plans to make the workshop a required part of future curricula.

Says Gifford: “DC is a very competitive market, and you have to really look at yourself as an individual and say, ‘Where are my strengths? Where are my opportunities for improvement?’ And if this is one of them, don’t be intimidated by that.

“As a leader of your organization, you’ll be called on to spread your message, and if you don’t get out there and practice, you’re never going to improve.”

This article appears in the August 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.