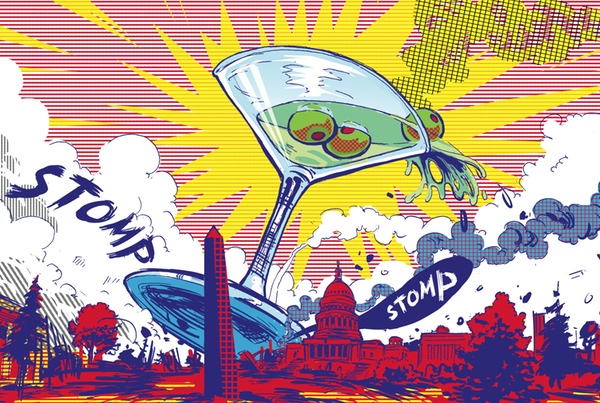

Illustration by Britt Spencer

I can’t remember when I last felt like such a jerk.

I’m at the bar of Dirty Martini, near DC’s Dupont Circle, and in front of me is a giant martini. By giant I don’t mean the sort of oversize cocktail that blights the average bar, those eight-to-ten-ounce behemoths that have made the notion of a three-martini lunch synonymous with binge drinking. No, I’m facing a monstrosity of a different magnitude—a 48-ounce drink that’s the bar’s new claim to infamy.

The $79.99 drink is a sweating, cone-shaped crystal birdbath festooned with a jar’s worth of olives. How to drink it? Gripping the stem, I find it hard to keep the top-heavy tub of liquor (almost two bottles’ worth) from tipping. Perhaps two hands on the bowl is the way to do it, like a Frenchman slurping his morning café au lait. The drink did come with straws, but though there are offenses I may be willing to commit and humiliations I may be willing to endure, drinking a martini through a straw isn’t among them.

“Who orders these?” I ask the waitress. “That is, other than dipsomaniacs?”

“Bachelorette parties,” she says. That strikes me as about right—the drink has all the subtlety of a steroid-bloated male stripper. And though Dirty Martini’s ginormous concoction is meant to be shared—the waitress, to her credit, didn’t want to bring one for me to drink solo—it’s still an absurdity, and a reductio ad absurdum sort at that, the ultimate expression of an overlong trend toward oversize cocktails.

Victor “Trader Vic” Bergeron knew something about large communal drinks—it was at his tiki joint that the Scorpion Bowl was invented, a tropical rum-and-brandy punch to be shared through long straws. But when it came to cocktails, Trader Vic had a sense of proportion. He demanded that his bartenders measure carefully. “My best advice is to make every drink as though it were to be the best you’ve ever made,” Bergeron wrote in the 1947 Trader Vic’s Bartender’s Guide, “and you can’t do this if you don’t measure.”

How big is his 1947 martini? One ounce of gin and a half ounce of dry vermouth. That recipe may come as a shock to modern sensibilities not only in its healthy ratio of vermouth to gin but in its pixie-like size.

Yet consider: The only martini worth drinking is one that’s ice-cold. You can finish a 1½-ounce version before it slips a single degree Farenheit. Then you can have another, served fresh from a narrow, ice-packed pitcher, and it will be just as frosty as the first. And should you choose to, you can have yet another.

At that point, with three vintage martinis under your belt, you still wouldn’t have come close to consuming the amount of liquor regularly served up in modern cocktails. And every sip of your vintage martinis will be cold, whereas the modern rendition is inevitably warm halfway through.

Which is what’s happened to the colossal beverage in front of me at Dirty Martini: It’s rapidly achieving room temperature. Even if I shared this cocktail—though I should note that one way to keep your friends is not to inflict apocalyptic martinis on them—it would be warm before a group could even dent it.

And so I fish out a few more olives to munch on my sober way out the door, leaving behind a shameful waste of gin.

When I get home, I make a martini in the size and proportions I prefer: 1½ ounces gin, ¼ ounce dry vermouth, stirred until the ice gets frostbite and then strained into a small, chilled cocktail glass. One nice cold olive. And no straws.

This article appears in the September 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.