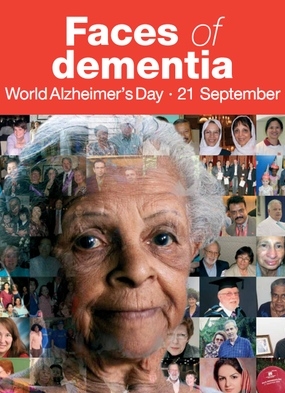

Today is World Alzheimer’s Day, a worldwide event that strives to raise awareness on all the “faces of dementia”—the patients, caregivers, family, and friends who encounter a disease that affects 5.4 million Americans.

An American develops Alzheimer’s every 69 seconds. By 2050, that time will be cut in half. By then, as many as 15 million Americans are projected to suffer from Alzheimer’s, the most common form of dementia.

But Alzheimer’s doesn’t just affect its patients. In 2010, almost 15 million caregivers provided 17 billion hours of unpaid care to those with dementia—valued at $202.6 billion.

Unfortunately, there is no cure for the disease that not only causes memory loss, but behavioral and motor problems, as well. We spoke with Rockville’s Dr. Kevin M. Gil, who has been working in the geriatrics field for 20 years, about Alzheimer’s and some up and coming treatments that may hold some hope for patients.

What are some major warning signs of Alzheimer’s that people should be aware of?

Typically, the first things that show up are problems with memory. These are things you commonly do, and then suddenly cannot follow through. The best example I can think of is of the recent coach, [Pat Summit], who was very meticulous and able to come up with the plans, the meetings, and the plays. She realized she had a problem when she couldn’t call the play for the next round.

Another common sign is executive functioning problems. Someone who once could balance a check book will say, “Now I can’t do it anymore, I keep making errors.” Or they’ll say, “Suddenly I find myself driving to the grocery store and I get lost.”

Or, the person used to be very engaging and social, but now you notice he or she isn’t joining in on the conversation. He or she becomes angry, irritable, and more withdrawn.

How do you officially diagnose someone with Alzheimer’s if there is no single test?

The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s requires a number of different things. The first one is just going through one’s history. What has happened to the person overtime? A lot of times they might not be aware of any problems, so family members can tell you things have been different. Maybe they’ve been forgetting things, they found the person getting lost with their car, or the bills being paid twice or not at all.

Sometimes, you can find problems on physical exams. The results in their neurological exams saying they’ve been having small strokes. Or there is decreased sensation in the feet or hands, perhaps indicating a vitamin deficiency.

Brain imagery can help, too. Doing either a CT scan or MRI can show up a tumor, stroke, or fluid collections on the brain. Finally, there’s the mini-mental status exam. It’s a 30-point scale that checks for memory impairment, orientation, problems with language, and problems carrying out motor activities.

Alzheimer’s typically affects people 65 years or older, but people in their forties or fifties can be diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s. Why does that happen?

Some people have a family gene. The most classic one is called apolipoprotein E. It’s a gene that’s associated with developing Alzheimer’s disease, and it clusters in families.

So since Alzheimer’s can run in the family, is there anything someone can do to decrease the chance of being diagnosed with the disease?

You can do mental engagement activities. In other words, increased social interaction, brain puzzles, sudokus, and crossword puzzles. People who do those things seem to have less incidence of Alzheimer’s. With people who exercise regularly, we also see less chance of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Make sure that you’re socially engaged. Do whatever it is that you’re doing to exercise regularly, and interact with people even more.

Once a patient is diagnosed, which treatment options are available?

We are on the cusp of being able to identify a couple of proteins found in the lumbar puncture. When you directly sample fluid from the spinal chord, you can test for a couple of proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease. You can start doing therapy to see if you can interfere with that process or progression.

But right now, treatments consist of medications that help out temporarily. These are called the cholinesterase inhibitors class. The most famous one is Aricept, but there are other ones, like Razadyne and Exelon. I say “help” because the actual process that causes brain cell damage has taken place already. These medications lessen or hold in position the person’s memory loss or brain deterioration for a short period of time.

People with Alzheimer’s will frequently be agitated or depressed. We try to regularize the environment so that it’s concrete, regular, and routine. Big clocks and big calendars on the wall, and the same routine every day. We also try to keep the person sleeping regularly.

In your experience working in geriatrics, what is usually the hardest part for the Alzheimer’s patients and their families?

The most traumatic thing for the person is taking their driving privileges away. Our independence is associated with driving. When you take away that ability, it’s devastating for the person.

What are some of the most common misconceptions about Alzheimer’s?

People with Alzheimer’s can develop a paranoid behavior. So the family members are accused of manipulating, stealing, hiding things from them. It can be very upsetting to the family member who tries to reason the person out of that fixed conviction. And of course, it’s not possible to do that.

Sometimes there are good days, where the person is pretty sharp, aware, and alert. And then, not so good days, when they’re more disoriented, combative, out of it, or withdrawn. That kind of back and forth over time is very hard for the family members to deal with.

For more information on Alzheimer’s, visit the Alzheimer’s Association.