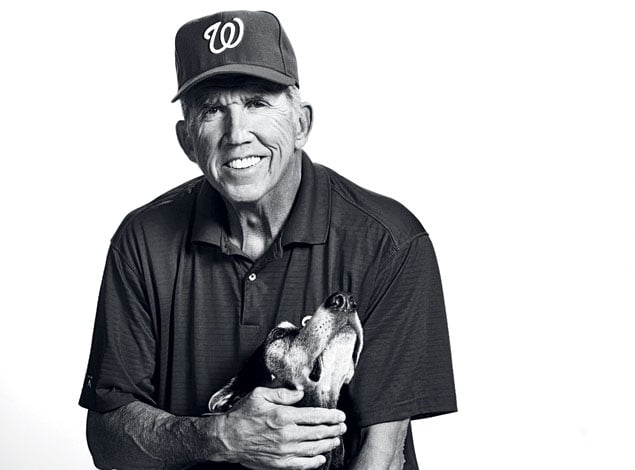

No one who knows Davey Johnson would accuse him of lacking confidence. He’s been called a lot of names; shy isn’t one of them.

But it had been 11 years since he coached in the major leagues. And he has had some medical problems. I asked Johnson about his energy level one recent morning in his living room in Winter Park, Florida, a posh community north of his hometown of Orlando. His eyes narrowed, then he flashed that wide grin and laughed.

“I’m in better shape than I’ve been in years,” he said.

He survived a ruptured appendix in 2005 and endured four surgeries to correct it. He’s had both shoulders repaired and had a heart-rhythm problem fixed a year ago. He’s had cataracts removed from both eyes. He says he has quit drinking from January to October.

“Now I can see with my own eyes if an ump misses a call,” he says.

He spits some tobacco into a Styrofoam cup. He shades his eyes from the sun pouring through the two-story windows in his living room that look onto a pool and palm trees.

“I might want to take some batting practice, too,” he says.

There’s more than his ability to swat fly balls riding on Johnson when the Nationals take the field on Opening Day, April 12.

He has a record of turning losing teams into champions. He took the New York Mets from last place in 1983 to World Series champions in 1986. The Nationals are in need of a turnaround. Since coming to DC in 2004, the team has never finished with a winning record. The fan base is soft. Nationals Park usually fills just over half of its 41,500 seats.

The Lerners have begun to show a willingness to spend serious money on established stars. Paying Jayson Werth $126 million for seven years and $100 million to extend Ryan Zimmerman’s contract comes to mind. But their investment needs to start paying off–with winning teams and higher revenues.

This spring, Johnson will have two of the most talented youngsters to hit the majors in a decade: pitcher Stephen Strasburg and outfielder Bryce Harper. How will the oldest manager nurture the two young prospects?

“My greatest love as a manager is seeing young players play to their potential,” he says. “My job is to create fertile ground for them to develop. That’s the sweetness of the whole deal.”

The word in some baseball circles is that Johnson will get just this one year. But word from the owner’s box is that this could be the start of Washington’s Davey Johnson era.

Why, I ask, did Johnson take the manager’s job?

He had a sweet consulting gig. He could show up at spring training or not. He could put on a uniform, kick the dirt, fungo a few flies.

“Happy as a clam,” he says.

He and his baseball buddies–Mel Stottlemyre, Whitey Herzog, and Bill Robinson among them–could get together to play golf or fish.

Johnson’s place in baseball is secure. He has the third-best record among living managers, behind Earl Weaver and Joe Girardi. No chance Davey would be bored. He might take a computer class, as he did at Johns Hopkins while he was in Baltimore. He applied statistics to baseball lineups decades before Moneyball made the movies.

So–why?

“It wasn’t the money,” he says.

Johnson wasn’t born rich. His father was a “tough Swede,” in his words. His dad was captured by the Germans in World War II, escaped, and was captured again but survived the war.

By the time Davey was nine, he had a paper route, sold potholders, and ran a root-beer stand after school. He played baseball well enough to land a scholarship at Texas A&M, and from there he signed with the Orioles in 1962.

“I used the salary from my first major-league season to buy a Pontiac LeMans convertible and a set of golf clubs,” he says. “But I also used $8,000 to buy a lakefront lot near Orlando.”

In 13 big-league seasons, mostly at second base, Johnson was an all-star four times and won two World Series rings, both with the Orioles, in 1966 and 1970. While he was fielding ground balls and managing teams, he was investing in real estate. He now owns an island, several choice building lots, a 72-acre fishing camp, and commercial and residential buildings. He’s a millionaire a few times over. So it wasn’t the money.

Family life is calm now. Susan is his second wife. They married in 1994. She owns a high-end clothing store in Winter Park. Their children and grandchildren live nearby. Susan and Davey have an agreement not to be apart longer than a week at a time, so they had to factor that into whether he took the Nationals job. Their bond has been defined more by tragedy than by baseball.

Johnson had two daughters in his first marriage, Dawn and Andrea, and a son, Davey.

Andrea was a surfer, a very good one. Sports Illustrated Jr. put her on its cover.

“She was not afraid of anything,” Johnson recalls.

But she wasn’t well. Andrea started hearing voices and was diagnosed with schizophrenia. She moved back to Orlando in her early twenties. When Johnson lost his job as manager of the Dodgers in 2000, he was happy to move back home. “I was burned out,” he says, “and I had a sick daughter.”

Andrea had spent time in Northeast Florida State Hospital in Macclenny, but she was considered well enough to come home. She deteriorated mentally and physically. In 2005, she was rushed to the hospital in septic shock.

“When I arrived, she was already on life support,” Johnson says. “I had to make the decision to pull the plug.” Andrea Johnson was 30.

“I believe in heaven,” he says. “I have to believe she’s in a better place. She’s surfing. She’s happy.”

Johnson was very close to Susan’s son, Jake. He was a “rubella child,” born with no hearing and no sight in one eye, because Susan had had German measles during her pregnancy. Jake needed constant care, often lived in group homes, and relied on specialists with the Helen Keller National Center.

About a year and a half ago, when he was 32, he lost the sight in his good eye.

“You can’t imagine how hard it was for a kid who could barely see to lose all his vision,” Johnson says.

Jake loved to feel the wind on his face as he rode in the back of Johnson’s speedboat across the nearby lakes. Johnson took him up to his fishing camp so he could feel the sand between his toes and wade in the water. Davey and Susan hired a teacher to help him communicate.

“We were turning a bad situation into a happy one,” he says.

About nine months ago, Jake developed a urinary problem. Doctors detected a blockage. During a test to determine the problem, he stopped breathing. It turned out he had pneumonia. He died at age 34 in the same hospital where Andrea passed away.

How does Johnson cope with the loss of both Andrea and Jake?

“Like any challenge, you have to try and look for the good in it,” he says. “You are supposed to die before your kids die–you’re there for them, they’re there for you. It doesn’t always work out that way.

“I don’t try to relive the past,” he says. “I’m a looking-forward kind of guy. It’s probably the key to the game of baseball for me, too, as a player and a manager. It’s not what I’m doing now but what I can do tomorrow.”

That still doesn’t explain why he took the job as manager of the Nationals.

“They could afford me,” he says.

I ask again.

“It was the challenge.”