If the name Bouvet Island doesn’t ring a bell, it shouldn’t.

Lying between Queen Maud Land in Antarctica and the Cape of Good Hope,

it’s the most remote place on Earth—an uninhabited volcanic island half

the size of Assateague. Glaciers cover more than 90 percent of Bouvet; the

rest is a mixture of frozen craters, impenetrable cliffs, and basalt

scraped raw by screaming gales.

Its utter isolation makes it the kind of place where you could

explode a nuclear bomb without anyone hearing it—which someone did in

1979, as flashing lights detected by an American satellite revealed. But

for Charles Veley, an executive for a Tysons Corner software company,

Bouvet was the ultimate holiday destination.

Veley’s interest wasn’t a result of mere curiosity. By 2003, at

age 37, he had traveled to 249 of the world’s countries and territories as

defined by Guinness World Records—more than anyone else who has ever

lived, according to his estimates. Yet when he approached Guinness to

claim the title of world’s most traveled man, officials told him that to

be recognized in its books, he’d have to set foot on one of the two places

that the previous record holder, John Clouse—a trial lawyer who had been

married seven times and traveled with holes in his socks—had never been:

Bouvet. The only problem was how to get there.

There’s a reason fewer than 100 people have been to Bouvet. The

nearest inhabited island, Tristan da Cunha (population 261), is 1,000

miles away, and ships heading to Antarctic scientific bases need to veer

days off course to reach it. But when a Russian contact tipped Veley off

that South Africa’s National Antarctic Programme was scheduled to dispatch

a support ship to Bouvet to fix a weather system, he booked a flight to

Cape Town and paid to hop aboard the ship.

During the voyage, Veley spent 72 days huddled next to a team

of hardy sailors and military personnel who in all likelihood would rather

have stayed home. When the vessel came as close as it could to Bouvet’s

craggy coast, it was left to a helicopter operated by South African Air

Force pilots to attempt the dangerous landing. Clouse had gotten this

close to Bouvet twice before, but each time weather conditions had forced

him to turn back. This time, as the aircraft left the boat, it struggled

through freezing temperatures, dense fog, and nearly 50-knot winds.

Swirling gusts dragged the chopper off course before it touched down on

Bouvet’s frozen rocks. Having reached what he called the “holy grail,”

Veley stepped out, snapped some pictures, and headed home a few hours

later.

He had made it to the end of the world and completed his

“lifelong quest.” Or so he thought.

• • •

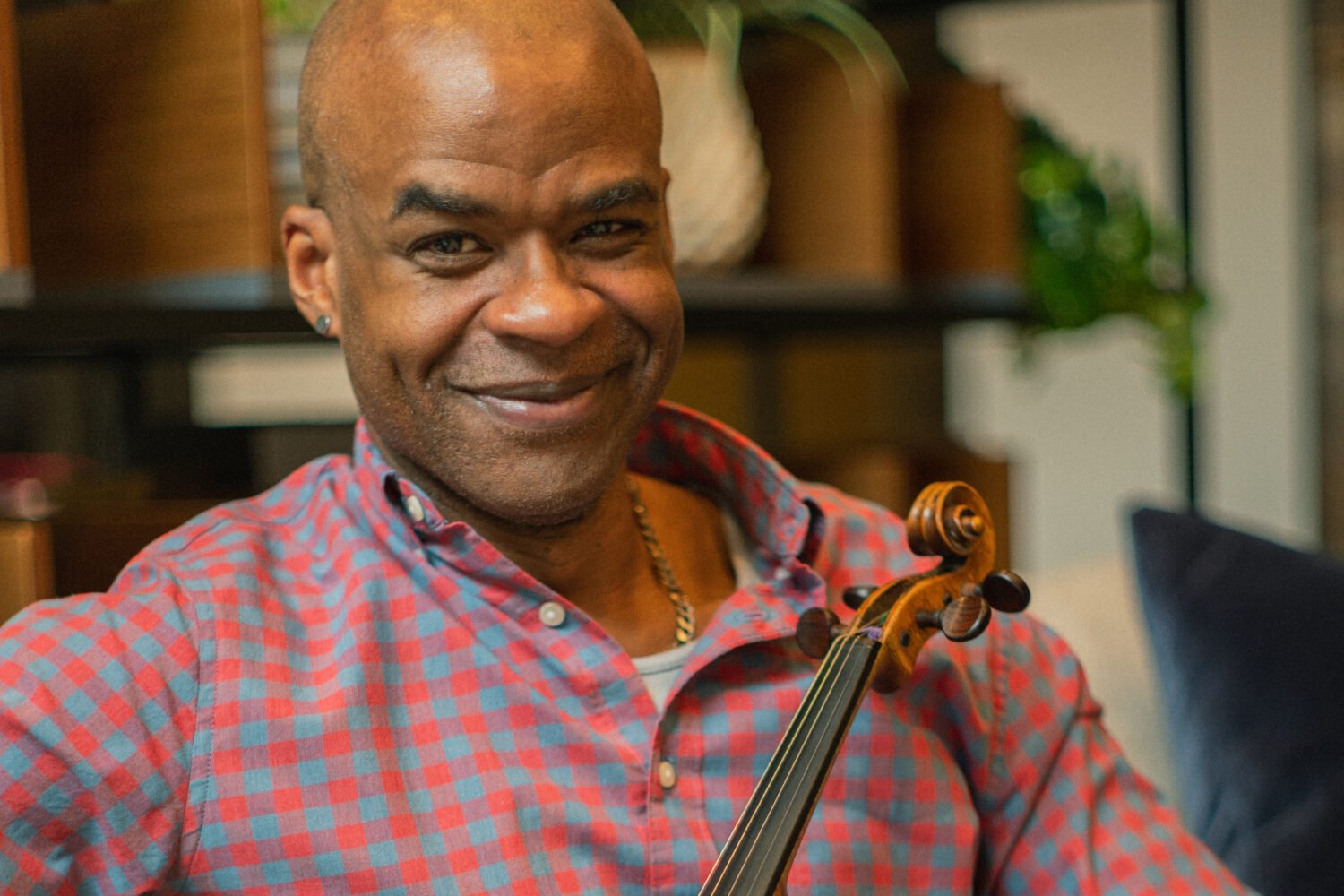

Now 47, Charles Veley is an extreme example of one of the

world’s most extreme groups: competitive travelers. Fueled by money, time,

and compulsion, competitive travelers dedicate their lives to going,

literally, everywhere. Often called “country collectors” or “tickers,”

they accumulate countries the way some collect baseball cards, and they

travel to such places as Aargau and Zug and everywhere in between. They’ve

carved the world into a jigsaw of must-see provinces, territories, and

atolls. What drives them is somewhat paradoxical: They’re on a quest to

“know” the world, and to keep score while doing it.

Says Veley: “There are people who aspire to see everything and

those who are actually able to do it.”

His parents didn’t have the money or interest to travel. They

sometimes found baby Charles crawling out the door of their Brooklyn

apartment. When he was old enough, he started studying maps, planning

imaginary trips on the family atlas, and wondering why his stamp

collection represented different colonies with images of the same king.

Yet by the time he was 18, Veley had left the US only once.

He got a scholarship to Harvard from the Air Force in 1983.

When he wasn’t crunching numbers as a computer-science major, he was

pulling T-37 jets out of corkscrew dives as a fighter pilot. Veley took a

break from his undergraduate flight training for a semester in Australia,

where he learned far more outside the classroom than in it.

“I never registered for class,” he says. “Instead, I discovered

you could easily go to places like Tahiti, New Zealand, and Fiji. I was

hooked.”

Shortly after Veley graduated, a doctor discovered a tiny scar

over his retina, leading the Air Force to discharge him. A few months

later, he bought a Eurail Pass and crisscrossed “every inch of Western

Europe.”

When he returned to the States in 1991, he and a few friends

founded MicroStrategy, a software company in Tysons. At the height of the

dot-com boom, the company was valued at $24 billion. Tired of 80-hour

workweeks, Veley retired in 1999 at age 34—MicroStrategy’s stock had risen

from $7 a share to $110—and sold some of his shares to travel full-time

with his wife, Kimberly.

One night in 2001, while flying 30,000 feet above the Pacific

Ocean, he picked up an in-flight magazine and learned about the Travelers

Century Club. At that moment, his wanderlust turned into a

competition.

• • •

The Travelers’ Century Club (TCC) is an organization for

international jet-setters. Its members—including a chapter in DC—have

spent a lot of time and money hopping across the globe to visit the 100

countries needed to gain admission. Not surprisingly, most of its 2,000

worldwide members are wealthy retirees. Having been to 60 countries at

that point, Veley embarked on a systematic tour of the planet with the

same vigor and spreadsheet mentality that had made him a

multimillionaire.

“Being a software guy, travel solutions come easy,” he says.

“It’s just logistics.”

During the next three years, Veley spent nearly $2 million and

traveled to every country he hadn’t visited. After traveling with him for

almost two years, his wife backed out to give birth to their first child,

but Veley wasn’t done. In 2002, he says, he traveled “259,649 miles, or

more than ten times around the world, including more than two months at

sea, and 254 flight segments on 94 airlines.” In 2003, he became the

youngest person to visit the world’s 320 countries and provinces as

recognized by the TCC.

To date, Veley has traveled 2.3 million miles, taken 5,100

flights, been to 325 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and learned five

languages—though he can order beer in many more.

“People who collect things want to complete the set—be it

baseball cards, stamps, or countries,” he says. “I’m no

different.”

Veley is living out a fantasy that millions of travelers can

only dream of. From Navassa to Nunavut, he has collected the kind of

stories that call to mind Dos Equis’s “most interesting man in the world”

commercials.

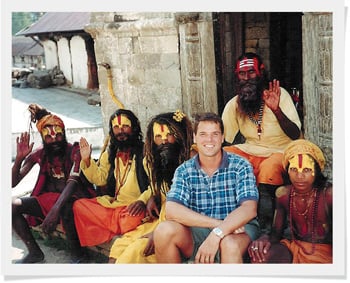

He once sped through Islamabad on the Karakorum Highway and

later briefed the CIA on the Taliban. In Russia, he was interrogated by

the KGB for four hours on suspicion of aiding Chechen rebels. He fended

off sharks while diving in the Pacific near Baker Island. And he nearly

froze to death 400 miles off the coast of Antarctica when a storm closed

in during a five-week ham-radio expedition, forcing him and a group of

Chilean workers to huddle together for 24 hours while waiting for a

helicopter.

He says travel has taught him the importance of being ready to

throw your plans out the window, such as when you’re in Kiribati awaiting

a skipper for a 1,000-mile voyage, only to have him show up three days

late and drunk.

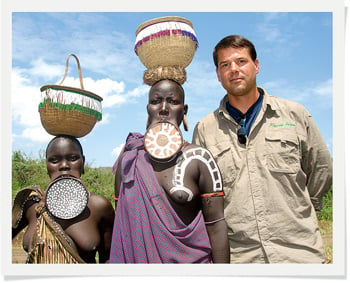

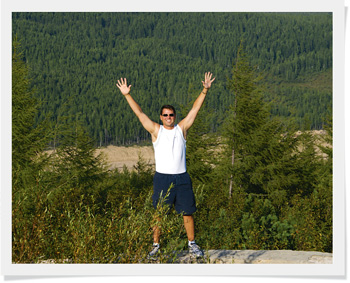

Veley says every place has been worth seeing, even when it

meant jumping off a ship to swim through ten-meter swells toward Rockall—a

speck of an island off the coast of Scotland—to touch its slick surface

and raise his arms in triumph before being swept out to sea.

“The more you travel, the more regional perspective you get,”

he says. “It helps you relate to different types of people, and the world

becomes more beautiful because of it. It helps you understand the

chaos.”

To a certain extent, Veley is right. A country collector is

probably much better than the average person at hopping into a taxicab,

studying the driver, and trying to name where he’s from—as Veley likes to

do. But when you put a premium on exotic destinations that only a handful

of humans have experienced, it can be hard to relate to those who don’t

share your passion. If you spend your life going to places like Oeucussi

and Voronezh Oblast, does that bring you closer to knowing the world or

take you farther from reality?

“The thing to remember about competitive travel is that you’re

dealing with a lot of wackos,” says Lee Abbamonte of New York City, the

youngest American to visit every country and who, at 34, is on a mission

to overtake Veley as the youngest traveler to visit every TCC destination.

“That’s not to say Charles is one of them—he’s a nice guy—but if you go

down the list of the top travelers, there are a lot of strange people and

divorcés with tons of time, money, and not much else.”

• • •

One of the few places Veley hasn’t been, ironically, is

Guinness World Records.

Not long after returning from Bouvet, he went to Guinness’s

offices in London with his passports, photos, and evidence for inclusion

in its 2005 record book. Soon thereafter, the chairman of the TCC wrote

letters of protest to Guinness stating that because it operates on the

honor system, it would be impossible to certify Veley’s claims. Guinness

concluded that it could no longer agree on an objective standard for the

title of most traveled man and eliminated the category.

The first problem with trying to quantify one’s travels is

determining how to dissect the globe. You could go by the International

Organization for Standardization’s list of 163 countries. But what about

the United Nation’s list of 193 recognized territories, The TCC’s 320

destinations, or the American Radio Relay League’s list of 340

places?

You can also argue that a trip to Guam shouldn’t count the same

as one to Kansas. Then comes the question of what constitutes a visit. Is

it enough to step across the border, or do you have to eat a meal there?

Spend the night? It’s a debate country collectors could have from here to

Karakalpakstan.

Seeking the validation he couldn’t get from Guinness, in 2005

Veley created Most Traveled People, a website that combines four

preexisting destination lists and allows users to carve the world into

further territories by voting. To get credit for visiting a place, users

submit one of several forms of proof, such as a passport stamp, an airline

ticket, a credit-card receipt, or a photo. Each month, members get ranked

on a scorecard.

Currently, MTP’s 12,204 registered users have divided the world

into 873 “countries, territories, autonomous regions, enclaves,

geographically separated island groups, and major states and provinces.”

Veley has been to 829 MTP locations—or 95 percent of the world—giving him

the title of most traveled human, at least by his rules.

“Most Traveled People’s goal is to be the official system of

record of serious travelers,” he says. “The phrase ‘most traveled’ means

geographic coverage of the land on Earth. There is no further subjective

criterion.”

In the past several years, Veley has been the subject of dozens

of TV and newspaper stories, some of which handed him the crown of most

traveled person without asking too many questions. But as the media

spotlight has intensified, so have the rumblings of competitive

travelers.

“There are a lot of questions out there,” says Lew Toulmin, a

Silver Spring resident and author of the book The Most Traveled Man on

Earth. With 288 countries under his belt, Toulmin is the 360th-most

traveled person on the MTP rankings. “Do you use frequent-flier miles to

quantify most traveled or miles walked or something else? Most people just

say number of countries, but even that’s questionable. I’d say Charles

certainly has as good a shot at the title as anyone.”

One person who disagrees is Jeff Shea, owner of a manufacturing

company in California who believes he has seen more of the world. Not only

has Shea been to every country; he’s also climbed the highest peak on each

continent, walked 590 miles across the Altiplano in Chile and Argentina,

and been part of an expedition that discovered a group of islands off the

coast of Greenland in 2006.

In response to Veley’s MTP site, Shea created his own far more

extensive list: Shea’s Register of the World, which consists of 3,978

countries and “sub-national provinces”—meaning that those wishing to tick

Azerbaijan off their list can’t just rent a car from Turkey and dip across

the border but have to set foot in each of its 78 geographically distinct

regions. Still, Shea admits his method isn’t perfect.

“There’s no real way to quantify who is the world’s most

traveled person, but no, I don’t think it’s Charles,” Shea says. “Charles

is the most traveled person according to his criteria, and I’m the most

traveled person according to other people’s criteria. There is too much

disagreement within the pack, and the fact is that the people who are

involved have a lot of self-interest.”

• • •

Veley’s main competitors will tell you how much they admire his

drive, but they also say that anyone who claims to have traveled to every

country in a few years isn’t stopping to see much.

In his book, Meetings With Remarkable Travelers, MTP’s

tenth-ranked traveler, Jorge Sánchez of Spain, has a chapter called

“Meeting With Charles Veley: The Speed of Light Traveler.” In it, he talks

about befriending Veley and inviting him to his home before they both

illegally entered the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. Sánchez—who has

worked as a dishwasher and collected fruit in different countries to pay

for his travels and has been jailed in five countries for illegal border

crossing—recalls that when Veley met with Guinness’s last record holder,

John Clouse, to tell him he had made it to Bouvet and bested his record,

Clouse refused to recognize Veley’s accomplishments, claiming his rival

was “traveling too quickly through the countries like a ping-pong

ball.”

While in the Sahara together, Sánchez writes, Veley admitted to

having traveled at a breakneck pace because “being declared most traveled

man would help him serve as an expert in international affairs.” When

Sánchez asked Veley what he thought of one of the Solomon Islands he

claimed to have visited, he reports that Veley replied: “I don’t know. I

didn’t visit Nendo, only its airport.”

Traveling like Veley, Sánchez concludes, “is like buying a

ticket to the cinema, and going back home without watching the

movie.”

Lee Abbamonte, who is currently number 16 on the MTP list—but

who says he has “no interest in wasting my time and money visiting random

rocks or icebergs in the middle of the ocean”—says: “I really like Charles

as a person, but I disagree that he is the most traveled man in the world.

The fact that he only goes to airports and then takes off again—does that

count? That’s what ticks a lot of people off about what he’s done. When I

bring that up with him, he just says that he had a goal and he wanted to

achieve it, but is that really achieving anything?”

Veley is only 44 ticks shy of completing his goal to go

“everywhere,” but these days his world tour is more or less grounded.

Short of funds due to a combination of his years on the road, the

stock-market collapse, and his recent divorce, he has returned to

MicroStrategy and 80-hour workweeks. When not flying to Washington to work

100 days a year here, Veley spends every other weekend at home in San

Francisco with his three young children. At the peak of his competitive

travel, Veley was sometimes away for as long as three months at a

time—often seeing his kids only on computer screens.

At the end of May, he’s hoping to squeeze in a trip that’s been

years in the making: After lobbying foreign officials and US senators,

Veley, Shea, Abbamonte, and a team of other competitive travelers are set

to embark on an expedition to the long-disputed Paracel Islands—a

constellation of sandbars off the South China Sea that has been closed to

foreigners. Aside from Bouvet Island, Paracel is the only Guinness

destination John Clouse never reached, which would make Veley the first

person to complete the entire list.

“It has special meaning to me personally, as a milestone, but

I’d never approach Guinness again at this point,” Veley says. “I have more

important things to worry about.”

After going to the ends of the earth to become the most

traveled man, he now claims that recognition is no longer important to

him. While his lifelong quest was once to make it into Guinness, Veley now

says his goal is “to enjoy life as much as I can and to provide for and be

a good model for my children.”

It’s possible that after almost a decade on the road, the

world’s most traveled man has finally found the perspective he’s been

looking for.

Eliot Stein (eliothendersonstein@gmail.com) is a Washington

writer and guidebook author.

This article appears in the June 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.