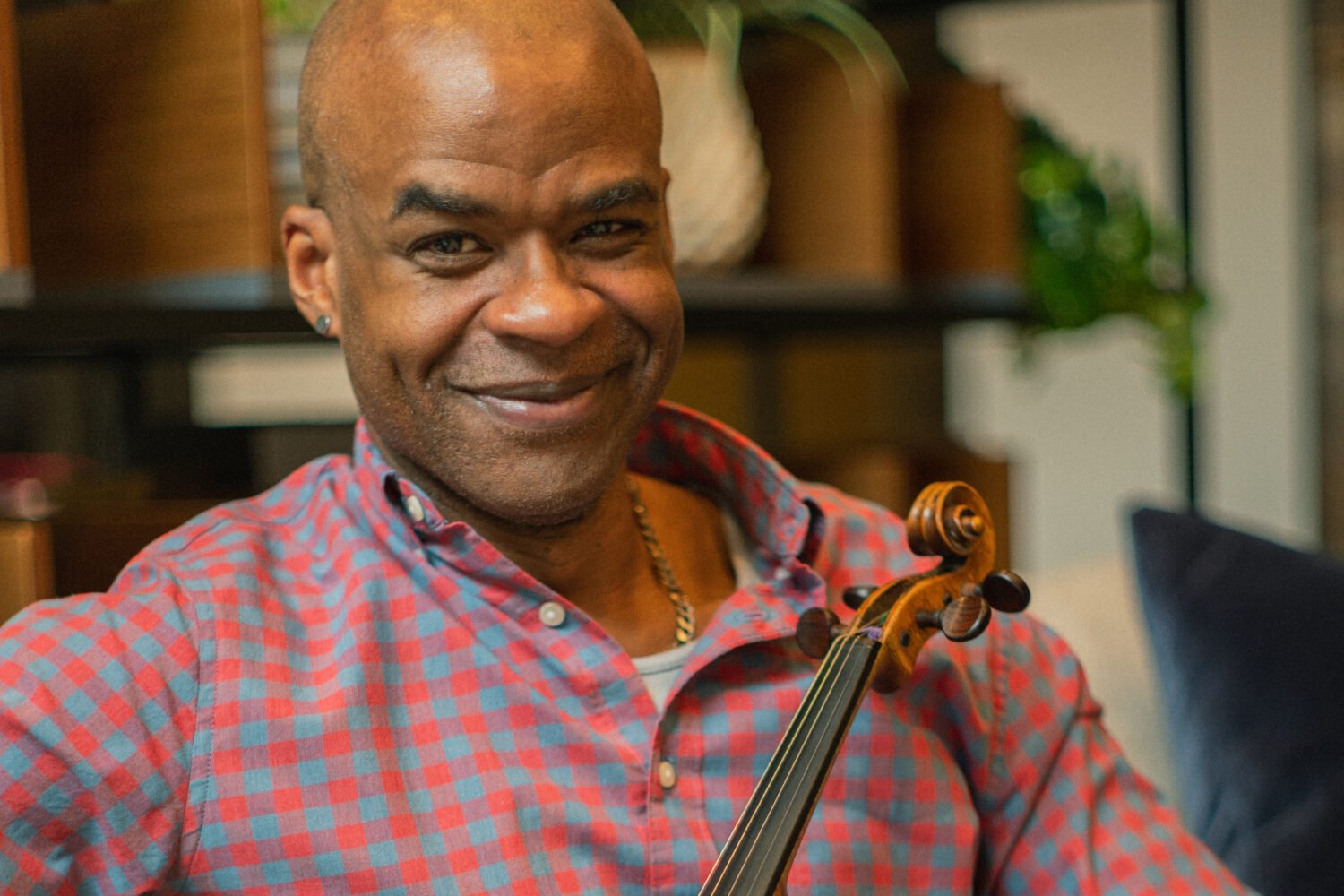

For Johnny Shockley, a lifelong resident of Maryland’s Eastern

Shore, working the water has always been more than a job.

“It was my first love,” he says. “My father was a waterman, and

his father was a waterman. In my view, there was nothing else that would

ever top being a commercial fisherman.”

Shockley, 50, spent his schoolboy summers working on his

father’s boat in the late 1960s and early ’70s, when there was still a

good life to be had as a waterman. But disease, pollution, overfishing,

and extreme weather have taken a grave toll.

In the late 1800s, when the so-called oyster wars raged, as

many as 15 million bushels of the bivalve were pulled from Maryland waters

each year. Today 99 percent of the state’s wild oysters are gone, and

annual harvests have dipped below 100,000 bushels multiple times in the

last decade.

Regulators have responded with increasingly tough rules, and it

was a longing for freedom from these restrictions that led Shockley to

look for a way to remain on the water without being shackled to the

declining profit margins and frustrating legal battles of the public

fishery.

Three years ago, inspiration struck—he’d grow his own oysters

rather than relying on what the bay could provide—and Hooper’s Island

Oyster Aquaculture Company was born. Today Shockley isn’t just a

practitioner of aquaculture; he’s an evangelist.

While traveling to spread the word of oyster farming this

spring, Shockley called me from the Atlanta airport, ebullient at the

reception he’d received along the Gulf Coast. “It’s a new revolution

around producing oysters,” he said. “It’s such a cool thing for the bay

environmentally and economically.”

• • •

On a crisp afternoon this spring, I drive across the Bay Bridge

to visit Shockley on Hooper’s Island, a chain of three islets about 20

miles southwest of Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. Along the way, I

pass forgotten boats sitting in tall patches of grass, the way rusted-out

trucks dot other rural areas, and the local volunteer fire

department—advertising an upcoming chicken-and-muskrat dinner—before

reaching the company’s headquarters beside the Honga River.

As we walk along the water’s edge, Shockley explains that for

decades the oyster was Maryland’s primary seafood catch and the economic

linchpin for the state’s watermen: “That’s what the entire seafood

industry in the state started upon.”

Early on, massive harvests began decimating natural reefs and

slowed down reproduction. Then, beginning in the 1950s, two diseases—known

as dermo and MSX—appeared in the bay. During the mid-1980s, droughts and

high temperatures spread the diseases, which proved far more disastrous to

the industry than pollution or overfishing.

While oysters declined, the blue crab became Maryland’s

signature seafood, as “Maryland-style” crab cakes cropped up on menus

around the country.

“What we’re doing,” Shockley says of his company, which he

cofounded with business partner Ricky Fitzhugh, “is reinventing the oyster

industry to try to help reestablish the oyster as the king-pin

economically.”

Aquaculture can refer to the farming of almost any type of

seafood. Oyster farming is a particularly sustainable subset because

oysters are filter feeders, removing excess algae and sediment from the

water. (Researchers think that the bay’s oysters once filtered the estuary

every three to four days; with today’s diminished population, it would

take a year.)

Oyster farmers raise larvae in fiberglass tanks, called

upwellers and downwellers, until they’re large enough to go into wire

cages and be set on leased land at the bottom of the bay. The general

process isn’t new—oyster farming has been documented as far back as

ancient Rome.

Beyond a metal door labeled algae room, Shockley swirls the

water in a glass beaker in which millions of tiny plankton are

multiplying. Water tanks, carbon-dioxide containers, carboys, and a

microscope fill the room.

Chesapeake Gold oysters, as Shockley’s are called, are

triploids, a variety of Crassostrea virginica—Eastern oysters—created

through genetic manipulation in the late 1970s to be meatier, more

disease-resistant, and faster-growing than their wild counterparts.

Because they don’t spawn, triploids can be harvested throughout the

summer, defying traditional admonitions to eat oysters only in months that

contain the letter “r.”

And aquaculture helps solve another problem facing watermen,

Shockley says: Oyster farmers can compensate for smaller harvests by

providing attractive, consistent, branded bivalves that restaurants can

serve on the half shell for a premium. Wild oysters harvested from the bay

command just a few cents each: A bushel containing 250 went for about $29

this past season, or about 11 cents each, according to Michael Naylor,

shellfish program director for Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources.

Shockley’s oysters, on the other hand, command about 60 cents

apiece.

He’s not the only one seeing the potential in oyster farms.

Along the East Coast, cultured oysters took in more than $44 million in

2012, says Bob Rheault, executive director of the East Coast Shellfish

Growers Association. In Virginia, which has a long history of supporting

aquaculture, the state’s growers sold about 28 million oysters, for an

estimated revenue of $9.5 million last year—$3 million more than in

2011.

In Maryland, the industry was inhibited by red tape until 2009,

when new oyster guidelines freed space for aquaculture and streamlined the

licensing process. A handful of companies were already in the game—the

Choptank Oyster Company, which produces a variety called Choptank Sweets,

was an early champion—but the guidelines led to an explosion of

entrepreneurs ready to try their hand at the business. According to

Naylor, Maryland has 87 new aquaculture leases pending.

Shockley isn’t just interested in growing his own oysters—he

wants to help other Marylanders do the same. When he became interested in

aquaculture, he investigated machinery and techniques used by labs and

research facilities. He believed the methods could be streamlined for

commercial purposes and began creating customized machinery that could be

used on his workboat. He now sells the nursery equipment, including

upwellers, downwellers, and huge cylindrical sorters that can quickly

divide oysters by size as they develop.

Shockley doesn’t fear competition. He sees an increase in

high-quality cultured oysters from Maryland as a way to boost the

reputation of all. “The more oysters we sell,” he says, easing into a

broad grin, “the more oysters we sell.” During a short harvesting season

beginning last September, the company took in about 100,000 oysters; he

hopes to take in 1½ to 2 million this year.

But how could even a booming mollusk market absorb such

abundance? As wild-oyster harvest rates shot up in 2012, the price

plummeted, leaving many watermen no better off than during average

years.

Shockley imagines a future in which Maryland oysters will have

the cachet to appear in what are known as “value-added” products and sold

across the country: Imagine succulent, flash-frozen oysters Rockefeller

available in Iowa or a fried oyster ready to pop into the microwave. It

wasn’t so long ago that blue crabs remained a local specialty; today they

appear on menus across the country and can be ordered frozen by the

dozen.

• • •

It’s not clear, however, that commercial watermen will embrace

the industry. For decades, watermen’s associations held political clout

beyond their numbers and used that influence to shift resources away from

oyster farms. Now the state government is beginning to support

aquaculture, but the transition isn’t easy for traditional practitioners.

“It’s sort of like asking someone who grew up hunting deer to put a fence

in their yard and start raising fawns,” Naylor says.

At an event in St. Michaels this spring, tensions ran high as

those making a living pulling oysters, clams, and crabs from the bay

insisted that aquaculture wasn’t for them, while Shockley exhorted them to

“think outside the box.”

He seems to have navigated these troubled waters fairly well

despite his apostasy. “Johnny is not the problem,” waterman Mark Connolly

says. Connolly, who operates a seafood community-supported agriculture

program with his wife in Talbot County, doesn’t believe aquaculture will

“fit our needs” but is more concerned with tightening regulations than

with competition from Chesapeake Golds. “I’ve shucked oysters with

Johnny,” he says with a smile as the two men proceed to do just that,

standing behind folding tables prying open the shells and setting them

next to lemon wedges and horseradish.

Back on Hooper’s Island, Shockley gives me a tour of some of

his growing business’s other facilities. “Every house you can see here was

built by the seafood industry,” he says, gesturing to homes in the

surrounding area. “In the 1800s, we had 20,000 people on the Eastern Shore

working in the oyster business. We’ve got a ways to go, but I honestly

believe we can get there again.”

Climbing into his truck, Shockley and I cross a long, thin

bridge that connects two of the Hooper’s Island land masses. The Honga

stretches out to our right while on our left blackhead ducks bob on the

bay.

Shockley says this will be the first year in decades when

neither he nor his father will be crabbing during the summer, but he

brushes aside any nostalgia.

“Without the oysters, I would probably be looking for a

completely different industry to get into,” he says, his eyes scanning the

water. “One of the things that really get me excited is I saw a new future

in the seafood industry for my son, who is 21. When we started this

company three years ago, he was ready to go to college and didn’t really

know what he wanted to do.”

After an internship at the University of Maryland’s Horn Point

oyster hatchery during his freshman year, Jordan Shockley is now a

marine-biology major at Salisbury University. When he graduates next

spring, he plans to work in the oyster hatchery his father hopes to open

in two years.

“I am excited that I can move to the next step,” Johnny

Shockley says, “that I can move forward.”

Cara Parks has written for the New York Times and Slate. She

can be reached at cara.parks@gmail.com.

This article appears in the July 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.