“Da” was Hannah’s first and favorite sound. When she said it at nine months in the pediatrician’s waiting room, another mother told me, “She must be thinking of her daddy.”

Frankly, I doubt it. Hannah’s daddy has a number, not a name. He is 741, an anonymous Los Angeles law student who was paid about $50 to produce the sperm that helped create my beautiful baby.

I don’t know him, and I never will. But I’ll be forever indebted to 741 for his part in making Hannah possible.

As I slid toward my mid-30s, I thought often of the child I always had wanted. Even as a toddler, I toted around baby dolls and asked neighborhood moms to let me cuddle their babies. It never occurred to me that I wouldn’t get married and have children of my own.

Yet suddenly it was my 35th birthday, and I was alone. My friends, family, and career were all satisfying. I was secure financially. But I knew motherhood was my destiny. Giving up on the idea of a loving husband was painful but possible; considering a life without a child was impossible.

I knew I would be a good and loving mother. The question was how to become one. Adoption was a possibility, but the urge to experience pregnancy and childbirth was overwhelming. I decided to explore the option of pregnancy first, but to keep adoption in mind.

Initially, I went through my address book for the names of all men I knew, past and present, who might be willing to father my child. Many had helped me move over the years—some several times—but this was a far different kind of aid I was asking for. I looked at the names of past lovers and felt squeamish about approaching them with such a request.

One of my dearest male friends once told me out of the blue that he would never serve as “Seattle Slew” for any woman. That was in the early 1980s. I assumed he had amazing foresight. I also knew he rarely wavered in his convictions.

In the age of AIDS, I quickly rejected the idea of a one-night stand, especially one that would have to take place at the height of ovulation.

That left what is often the stuff of jokes and sitcoms—a sperm bank.

• • •

“Sperm bank.” The words were almost too siily. No one I knew ever talked about sperm banks. For all I knew, massive buildings in New York and Los Angeles had “Sperm Bank” etched into their concrete.

I started by calling my gynecologist and asking if she knew of any places in the Washington area where I could become artificially inseminated. She gave me a long list but urged me to call the fertility clinic at DC’s Columbia Hospital for Women Medical Center. She said they were expensive but “scientific.”

So, trembling and sweating, I entered the fertility clinic for the first time on August 14, 1991—one month after my 35th birthday.

My journal entry that evening: “Not sure what I expected, but certainly not the innocuousness of the waiting room—two women and a man sitting around in a spacious room reading current magazines. They looked so calm, unlike the turmoil I was feeling. I felt some shame at being there.”

As I sat in the waiting room, a UPS delivery man carried a large box to the receptionist’s desk. I was picturing motile little sperm swimming frantically inside, but I found out later it was a shipment of envelopes.

When my turn came, the receptionist called out “Mrs. Abrams,” a mistake that seemed comforting at the time. I saw Dr. Belinda Marascalco, then with the hospital’s Reproductive Endocrinology Department. She offered no lectures on the inadequacies of single motherhood, no judgments. I realized as she spoke how little I knew of the reproductive process and how much I would have to learn. I also realized how truly committed I was to bearing and mothering a child.

I left the clinic with a temperature chart to keep track of my cycles and with a lot of hope. A week later, I wrote in my journal: “Sadness arises from a feeling that I am giving up on doing this in the traditional way. Envy of others who have it all. Unbearable sorrow that there is no intimate love relationship in my present. I have a need to fully accept this so that I can let go of it and make way for the joy that can follow . . . .

“Sweet child of mine—with every pang of indecision, there are fifty prayers for your safe arrival. Your life-altering presence in my world is so eagerly and lovingly awaited.”

• • •

I left the clinic on August 29 with a list of donors from California Cryobank, a Los Angeles-based sperm bank, and a sense of tremendous anticipation.

California Cryobank was one of two choices open to me-the other was in Louisiana. I stuck with the Los Angeles sperm bank because it has an excellent reputation for screening donors, and because I liked the idea of my East Coast baby-to-be having some California blood in her or him.

The donor book listed more than 100 donors. Each listing gave the basics—blood type, ethnic origin, hair color and texture, height and weight, educational background, general medical history, family history, and some essay answers.

I combed the list, not sure what I was looking for. Finally, I decided that I wanted a donor who could give the child all the physical characteristics I could not—long legs, a tall, slender body, and good eyesight. I screened out anyone with a relative who had died of cancer or other possibly genetic diseases. I didn’t care about religion or hair color, although I admit that SAT scores were marginally significant.

My first two choices were unavailable. Over time, I would discover that many of the donors would be available one month but not the next, and sometimes not for months at a time. Fertility clinics nationwide were using the California Cryobank listings, I was told, and there is a finite amount of donations one donor could make.

Rationally, this made sense, but it seemed unfair when I was stuck with my third or fourth choice. Too many other women shared my taste in genes.

• • •

On September 30, at 2:40 PM, I was inseminated with the sperm of a 5-foot-11 blond with a degree in geophysics from Dartmouth. I was won over by his handwritten message to any recipient of his DNA: “Despite the business involved, there is still something sacred about this exchange. The child you may bear is, in a sense, a part of my very existence. I feel confident, though, that you will treasure this child as I treasure my life.”

It didn’t hurt that he had listed two major geophysics awards he had won at Dartmouth and what years he had won them. Even though I had signed very legal-looking documents agreeing that I would never try to locate the donor, I could at least find a yearbook and see what he looked like.

Unfortunately, his attributes didn’t include a high sperm count or motility. When a specimen is defrosted, it is analyzed and given a number between 1 and 4 based on many factors—with 4 the most desirable. The Dartmouth grad was a 2-plus. Two weeks later, despite a certainty that I was nauseated and slightly lightheaded, I got my period.

Like failing to become pregnant in more conventional ways, failing with donor insemination is accompanied by disappointment and fear that infertility is one’s lot in life. At the time, one of my friends pointed out that the process of trying to conceive was no fun my way.

I disputed that. While it-wasn’t soft lights and Luther Vandross ballads, there was an element of fun and anticipation. Several times during the six months it took to conceive, I would spend an hour or more in the center’s conference room poring over lists of donors. Sometimes nurses on their lunch breaks would help me in my decision. It was a bit like shopping—starting out with a good idea of what you want but finding yourself distracted by the unexpected.

When reviewing my choices, I would write down the numbers of six or seven donors. Carotin Ringwall, the nurse in charge of the sperm-donor program, would then call California Cryobank to see which were available. Not knowing if the donor I used one month could be used in subsequent tries was unsettling.

It was equally unsettling to tell the people in my life what I was doing. I told my mother in the middle of a swimming pool in August, assuming that her New England upbringing would preclude her making a scene in public. She threw her arms around me and said she had always wanted me to have a baby.

I told my father around the time of the second try. The day before, I had written: “I am filled with apprehension. I know he will be disappointed. Of course, everyone else I’ve told has been genuinely happy for me. But it’s Dad’s own role which is being eliminated from the scenario I’m creating. That must be painful.” He reacted as my mother had and began talking about his excitement over having a second grandchild.

Eventually I told most of my friends and family. Unequivocally, they were supportive. In time, my undertaking took on the spirit of a communal project—I was able to let out my breath.

• • •

I served on a jury in DC Superior Court in early October. The case involved a borderline-retarded teenage girl who had been repeatedly raped over time by her mother’s boyfriend. Sitting through the trial and wondering if I were pregnant, I began to hate what a lousy world this can be and to feel such a sense of loss for the teenager.

During long periods of waiting in a dingy jury room, I would reflect on what I had to offer a child. I reviewed my finances, my job situation, my circle of friends and family—all were in order.

The pain revealed daily in the courtroom gave me space to count my own blessings. By the time a verdict was rendered, I was convinced that my decision to bear a child was a sound one.

On October 2, I was again inseminated with the Dartmouth donor. That evening I wrote: “If there were anything I could do to ensure conception, I would do it. In the meantime, my morning temperature has acquired great significance. The higher it goes, the better. In my yearning, I don’t jump or run in Jazzercise. I hold imaginary conversations with something smaller than the tip of my pen, which may or may not exist.”

Three days later, I wrote, “I am vigilant. I am listening for you.”

In mid-October, Phil Donahue—always one to plumb the depths of human emotion—did a program on “Single Mothers by Choice.” I was fascinated by how normal all the women seemed, by how beautiful their children were, and by how judgmental the audience was.

Having booked guests onto Donahue as part of my public relations job, I know that the audience is primed and urged to be combative, but it was still hard. I was left wanting to ask them, “Who decides under what circumstances a child should be brought into this life?” I was already fighting for my baby’s tenuous place in this world.

• • •

My third round of inseminations—I would do it two days in a row each try—came in mid-November with a 6-foot, red-haired swimmer. I was hoping that his swimming might translate to his sperm’s abilities. It’s amazing the clues I would pretend to ferret out. But I was wrong—I’m not placing blame here, but somebody didn’t swim fast or far enough.

The donor for my fourth round was chosen out of desperation. No one I truly wanted was available, and my swimmer was tapped out, so to speak. I was beginning to take this personally. Had he been too busy to spend five lousy minutes in a Los Angeles clinic? Didn’t he know I was counting on him?

As I prepared for this December try, I wrote: “How did I pass the days before I became obsessed with menstrual cycles, basal temperatures, and men’s sperm counts?”

My most fertile day happened to fall on a Saturday in December, which was the day of Columbia Hospital’s holiday party. The clinic’s weekend staff had dwindled to a precious few.

Arrangements were made for me to visit the clinic between 8:30 and 9 that morning to pick up a vial of my donor’s sperm to take home. The woman working in the andrology lab showed me where the specimens were stored and even put a tiny bit of my donor’s sperm under the microscope so I could see all the activity. She seemed happy for the company and cheerfully explained how to insert the specimen. I should have listened harder.

Placing the vial in my bra to keep it warm, I pushed the DC speed limit and reached my Capitol Hill home in record time. In the kitchen, I successfully emptied the vial into the syringe I was given—but I lost most of the sperm down the sink while trying to tap out any air bubbles. Literally, $150 and a lot of hope went down the drain.

After the fifth attempt failed, I decided to get away from it all. I ended up in the middle of the southern Utah desert at a relaxing spa, where I spent my days assiduously not monitoring my basal body temperature. After a month of hiking in canyons too beautiful to describe and eating gourmet vegetarian food, I felt ready to try again.

But I was no longer patient. This time I took Clomid, a fertility drug, and asked the clinic to select donors who had proven track records. That’s how I ended up with 741. The Prince of Fertility. Mr. Super Sperm Count. He was no slouch in other departments, either: green eyes, curly red hair, a law student who scored 1400 on his SATs and whose only physical problem is asthma.

His essay-question responses looked like he was in a hurry to complete the form, but he did manage to write about himself: “fun loving, active, patient, athletic, enjoy life, hard-working, driven, intellectually stimulated.” He’s someone I think I would have liked knowing.

On March 9, 741 ‘s defrosted sperm registered a 4-plus on the fertility scale. Those little guys were ready to party. Thanks to Clomid, I had produced five eggs just waiting for the music to begin.

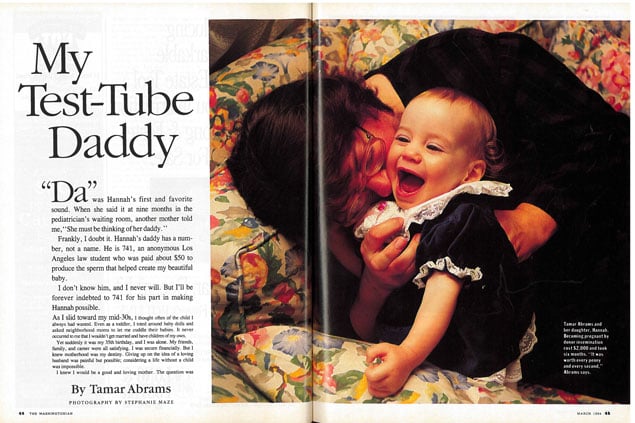

Sometime that day or the next, Hannah began her journey into my world. I had spent about $2,000, six months, and many ups and downs. It was worth every penny and every second.

• • •

Just as my pregnancy was getting underway, Dan Quayle gave it a certain cachet when he lambasted Murphy Brown, the sitcom character played by Candice Bergen, for giving birth to a child out of wedlock. My only concern was that people might think my child-to-be had been inspired by television.

Pregnancy is a state of extreme emotion and enormous expectations, and I was caught up in the excitement and only rarely worried about the method I had chosen. I was too busy finding a new home and looking through baby-name books—one of the advantages of single motherhood is that a baby’s name doesn’t have to be negotiated.

Most people responded to my news with one of two exclamations: “Are you crazy?” or “You are so brave!” I felt neither. Most of the time I just felt happy.

I moved from Capitol Hill—where I had lived since 1980—to a brick house in Arlington with a large, fenced back yard. My baby might not have a father, but she would have all the trappings of a traditional home.

The loneliest times were when the miracle of my baby was revealed to me through fetal monitoring or sonograms. I desperately wanted a husband with me at those moments, but I learned to take friends or family along instead. Soon, Virginia Thompson, my obstetrician, had to bring extra chairs into her office for my friends. The sonographer would just smile when one of my friends looked at the monitor during an early sonogram and announced, “It looks like a Buick to me.”

One of my dearest friends, a baker at Marvelous Market, would deposit freshly baked loaves of bread outside my door during a time when eating anything else was difficult. My sister sent me dozens of silly pregnancy cards, delighting in altering the printed messages that referred to both father and mother.

In early July, amniocentesis revealed that I was carrying a girl. I had always wanted one—mostly because of the shopping possibilities—but I was also relieved. Somehow it seemed easier to raise a girl alone than a boy.

• • •

As the summer of 1992 ended, I had to pick a labor coach. I chose my friend Lisa Swanson, whose Minnesota Lutheran calm seemed to bode well for a long, painful labor. Other friends were lined up as backup coaches. Team Abrams was in place.

Surprisingly, we weren’t the only same-sex labor team in Columbia Hospital’s birthing class. Several women showed up with their mothers. Oh, how the times are changing.

Not for me one of those last-minute dashes to the hospital. No water breaking on the subway. My labor was induced, at my doctor’s recommendation. During the twelve hours of actual labor, a parade of family and friends passed through to offer support: my father, five friends, and nurse Carolin Ringwall, along with Lisa Swanson and my mother, both of whom stayed throughout the process.

I don’t remember much. Lisa kept notes and insists that at various times I mentioned Krakatoa, the subway, and smelling smoke. By the end, I was reduced to begging and swearing.

Hannah Lily Abrams was born by Caesarean section at 3:38AM on Tuesday, December 1, 1992. Through the haze of drugs and fatigue, I looked at this tiny, puffy child and felt with certainty that this was the greatest accomplishment of my life. The lack of a husband in no way diminished the pride and joy of that moment.

My love was enough.

• • •

I have lost count of the times people have said to me, “You are so lucky to have such an easy baby.”

Hannah has slept through the night almost from the beginning, and even now, at 15 months, she plays quietly in her crib until faIling asleep at 7:30 PM. She arises most mornings at about 6:30, smiling and singing to herself. I wonder sometimes if Hannah sensed early on that there was no fall-back player, that she couldn’t risk wearing me down.

Maybe it’s just that together, we have been so fortunate. My employer let me set up an office in a spare bedroom of my home. For day care, our beloved babysitter is only two houses away. On warm days, I pause from working to hear Hannah and the other children laughing as they play in the babysitter’s front yard.

We belong to an informal club of eight other Arlington women and their babies , born within a few months of each other. One of the other women is also a single mother by choice. We seem to fit in well.

Only rarely does Hannah’s lack of a father come up, but I do make a point of having her spend time with men. She seems to bestow her grandest smiles on them. And she has developed a fascination for beards, one that I share.

Like every other parent I know, I have great hopes for Hannah’s future—and great fears. I worry that she’ll feel isolated by her difference. I worry that someday she’ll be angry with me for not being able to answer her most needy question. And I worry about the environment and the status of women in the United States and the increasing intolerance practiced in the name of religion. Just the usual worries of someone who has had the audacity to bring a life into this fretful world.

Other single mothers by choice have told me that children don’t ask questions until they’re ready to hear the answers. I trust Hannah’ s instincts. She seems to have a pretty good handle on her needs so far.

And I trust my ability to listen to her, to really hear her, and to provide her with information that will make her feel comfortable and loved.

The overriding promise I have made to Hannah is always to answer her questions honestly. I have no shame about her conception or birth, and I hope she will inherit that.

• • •

Last summer a camera crew from the Post-Newsweek TV stations came to my home to interview me about a new Census Bureau report. It showed that the number of never-married mothers with graduate or professional degrees had doubled between 1982 and 1992.

The cameraman videotaped Hannah flashing her most winning smile and holding up her plastic telephone. He taped us walking down the steps of my house to the sidewalk and past the neighbors’ lawns. He taped us standing on the porch next to the tiny American flag that had been planted in the yard on the Fourth of July.

As the crew was packing up equipment, the reporter told me he was heading downtown to interview the head of a large conservative organization who felt that women like me were ripping apart the fiber of the American family.

The reporter had just spent an hour in my home. He had watched me wake Hannah in her brightly decorated nursery. He had held her as she played with his microphone. I asked him if he thought we were ripping apart the fiber of the American family.

He considered it. He admitted that, when given the assignment, he hadn’t thought much about women’s bearing children without husbands. Now he said, “I can’t help thinking this was meant to be.”

Tamar Abrams is a writer and communications consultant with a special interest in global health and development, foster care, and adoption and gender issues. She can be reached at tamarabrams@verizon.net or on Twitter @tamarabrams.

This article appears in the March 1994 issue of The Washingtonian.