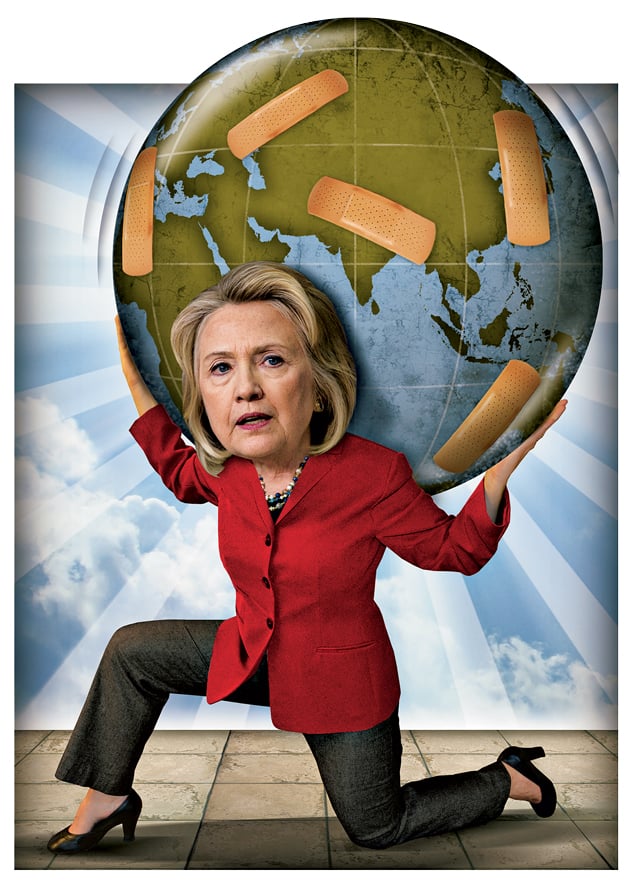

Take a minute to play communications director for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential run. Your task: come up with a 30-second spot to run in the early primary states about your candidate’s four years as Secretary of State.

What part of the world do you start with? Iran? John Kerry now owns, for better or worse, the effort to bar the mullahs from getting the bomb. The “pivot to Asia”? The pushback on China in the Pacific has yet to take any visible shape beyond President Obama’s patented phrase. The “reset” with Russia? Really? Putin’s a pal now?

Anyone putting together a brag clip about Clinton’s tenure at State faces the question a Democratic strategist put to me in a recent e-mail: “Can she translate her record into accomplishments that are meaningful to Iowa farmers and flinty New Hampshire Yankees?”

An equally important requirement for you, the messaging guru, will be to erase from voters’ minds the footage—currently running nonstop in opponents’ negative ads—of Clinton angrily responding to Republican senators probing what she knew, and when, about the 2012 Benghazi terror attacks that killed four Americans: “What difference, at this point, does it make?”

Suddenly it dawns on you, the communications director: This isn’t going to be so easy after all . . . .

More than 150 years have passed since a Secretary of State ascended to the presidency. There’s just something elitist—a little too think-tanky—about diplomats for ordinary folks’ tastes. When Obama handed Clinton the office after he kayoed her in the 2008 Democratic primary, though, he allowed her a dignified hand up from the canvas. It was understood that by enhancing her global stature and keeping her on the front pages, Obama was also positioning her as frontrunner to succeed him. But five years later, the office looks less than ever like a steppingstone to the presidency.

• • •

While Clinton is the most welltraveled diplomat in American history, having visited 112 countries, her legacy is thin. Her one clear-cut triumph—a dramatic improvement in relations with Myanmar—won’t elicit huzzahs on the hustings.

“She left office without a signature doctrine, strategy, or diplomatic triumph,” liberal analyst Michael Hirsh wrote in Foreign Affairs magazine.

“When it comes to issues of war and peace, or matters of high strategy, she really hasn’t left a mark,” Aaron David Miller, a Mideast scholar and an adviser to six Secretaries of State, wrote on ForeignPolicy.com.

Miller admits that Clinton never had much of a chance to make an impact— perhaps because, as has been well documented, the White House never fully shed its distrust of her from the ’08 campaign. “The war on terror was run out of the [Central Intelligence] Agency and the White House,” he says. “All the big strategy with respect to managing the US-Israeli relationship, and the big bilaterals with Russia and China, again, I think were primarily shaped by the White House.”

Even after Clinton proved she was a team player, campaign veterans remained wary of her popularity.

“Do I think that, because she’s Hillary Clinton, people think she’ll maybe have more stroke, and that makes people nervous? Probably,” says Tom Nides, former deputy Secretary of State for management and resources under Clinton. But given the “White House-centric” nature of modern foreign policy, Nides says, “this team exhibited the least psychodrama of a national-security team in a decade and a half.” He estimates that Clinton’s team got its way on “80 percent of what we cared about.”

“She and the President were not deep intimates,” says Anne-Marie Slaughter, State’s director of policy planning under Clinton, “but they had a good relationship. Her voice was listened to.”

Yet ask Clinton’s closest aides to identify her greatest accomplishment as Secretary and the answers immediately plunge us into some deathly lunch-hour foreign-policy panel at Brookings or CSIS.

“She provided leadership in reorienting American foreign policy and reshaping global perceptions of US foreign policy after the eight years of the Bush administration,” says James Steinberg, Clinton’s deputy Secretary of State.

“She was the first person who really realized that we have to do diplomacy differently in the 21st century,” Slaughter says. “She realized that we can’t act as if diplomacy is just a bunch of nicely dressed gentlemen in dark-paneled rooms. She appointed ambassadors to the tech community, youth, women, the entrepreneurial community. She knew we can’t just do government-to-government, that we also have to do government-to-society and society-to-society.”

Slaughter credits Clinton with elevating “economic statecraft”: “In an age of non-state actors, she was the first person who knew how to adapt to that world.”

Condoleezza Rice, who was Secretary of State from 2005 to 2009 and is no one’s idea of a pinstriped throwback to John Foster Dulles, disputes those claims.

In an e-mail responding to a request for comment from Rice, Georgia Godfrey, her chief of staff at Stanford University—where Rice teaches—wrote: “The fast pace of technological advancement in the twenty-first century required the Bush administration to quickly adapt new methods of diplomacy in a post- 9/11 world.”

Rice ordered Foreign Service officers to leave world capitals to engage in the provinces and to push AIDS relief and girls’ education, especially in newly liberated Afghanistan. She also saw diplomacy as a means to “directly improve the lives of people,” Godfrey asserts, and made economic development part of her program.

Rice drafted the computer giant Cisco and the cosmetics company Avon to spearhead public/private partnerships in Lebanon and the Palestinian Authority, respectively. And it was Rice who hired a 24-year-old Rhodes scholar named Jared Cohen, who built State’s social-media infrastructure. Clinton kept Cohen on staff.

In the run-up to 2016, Clinton’s diplomacy will also be compared with the résumé of Vice President Joe Biden, who is a leading rival for the Democratic presidential nomination. A longtime member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Biden has visited more than two dozen countries as Veep. He has not been generous about Clinton’s record.

Administering the oath of office to John Kerry last February, Biden gushed, somewhat pointedly: “In the history of our country and management of our foreign policy, I can honestly think of no man or woman whose hands I’d rather that responsibility be in than John Kerry.”

• • •

Clinton’s former advisers stress the issue for which she is perhaps best known, dating to her years as First Lady: the empowerment of women and girls.

On her first visit to China as Secretary of State in 2009, she spent more time debriefing a group of female lawyers and doctors—in a fascinating roundtable discussion at the US Embassy in Beijing—than she did in her closed-door talks with the Chinese foreign minister.

P.J. Crowley, who was Clinton’s spokesman at State for two years, remembers the impact the Secretary made in 2010 when she and her entourage swept into an auditorium at Dar Al-Hekma College, a women’s school in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. “They shrieked when Clinton walked into the room,” Crowley says. “They knew what she meant. It was a moment when I understood that this was more than just a speech or a town hall. It had real meaning for that country and for the women in that region.”

Scenes like this matter in both real and PR terms, not least because women have outnumbered male voters in presidential elections since 1964. But Clinton can’t win with women, or by being a woman, alone. In 2016, she’ll be running not on her record at State but as the survivor of one of the most storied careers in the annals of politics. She has come through an extraordinary series of land mines, self-inflicted wounds, and sneak attacks that would have felled figures of lesser spine.

Her electability is based in part on precisely this: her ability to rise above and move forward in the grimmest conditions. Anne-Marie Slaughter remembers watching Clinton cope when, in February 2010, the then-anonymous group WikiLeaks began posting online more than 250,000 classified diplomatic cables leaked by an Army private.

“It was just a nightmare,” Slaughter says. “And here she is—it’s not even your fault, not even your agency’s fault, and every foreign leader now knows what was said about them in private. She jokingly called it ‘my apology tour.’ A lot of foreign ministers were outraged. They wouldn’t even talk to the United States! She would just listen patiently to each one, and then say, ‘You know, there have been plenty of nasty things said about me,’ and so on. And they started listening again.

“It was amazing. She was able to take the batterings she had suffered and use them to her advantage. That’s a pro.”

James Rosen (james.rosen@foxnews.com) is chief Washington correspondent for Fox News.

This article appears in the January 2014 issue of The Washingtonian.