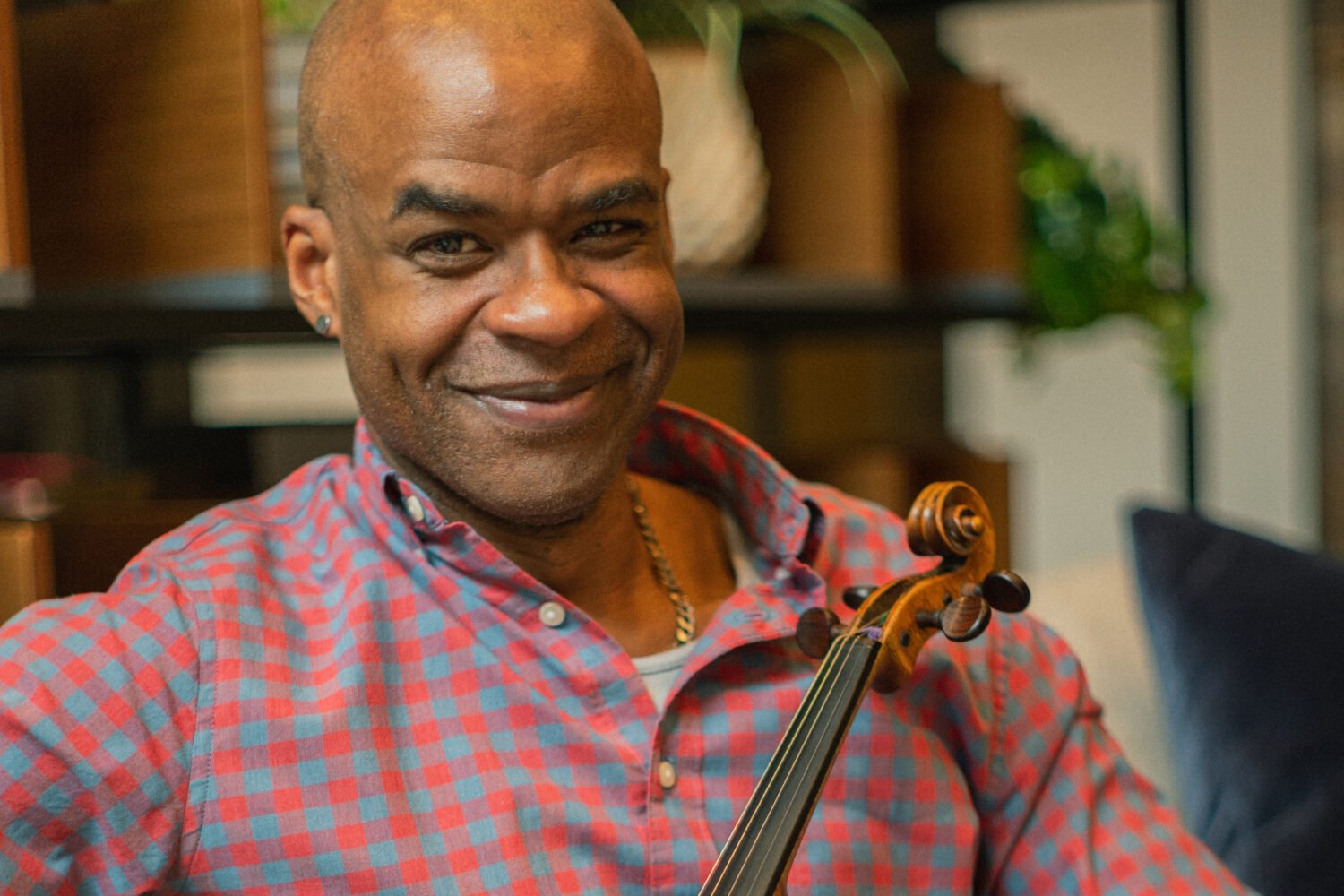

For more than 40 years, Charlie Bessant was that guy.

The guy who’d slink out of every party to catch a smoke on the sly. Who’d walk for blocks late at night through his dicey DC neighborhood to score a pack of Marlboro Lights, no matter the weather.

Bessant tried and failed to quit many times. He used the nicotine patch, gum—you name it.

“I always thought, ‘I’m going to quit—this is my last pack,’ ” says Bessant, 64, now living in Silver Spring and semiretired from his work making mounts for museum exhibits. “A big percentage of packs I bought were the last pack I ever bought.”

But on a fall day in 2009, Bessant walked into a building at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore. In Room 3102, he was given a dark-blue capsule to swallow. He lay down on a couch and nestled inside a cocoon of blankets. He put on eyeshades and headphones and waited for the blue capsule to do its thing.

And he never smoked another cigarette again.

Bessant’s method of kicking his cigarette habit was unorthodox, to say the least: The blue capsule contained a healthy dose of psilocybin, the active ingredient in hallucinogenic—a.k.a. “magic”—mushrooms. Bessant was a volunteer in the world’s only study investigating whether psilocybin can help cigarette smokers quit. Although most people associate the drug with tie-dye-clad college students and Phish concerts, scientists are discovering that when used in a carefully controlled research setting, psilocybin may achieve something far more powerful than a fleeting, rapturous high. It may actually change lives.

• • •

The smoking study—for now, a pilot feasibility study—is the brainchild of Matthew Johnson of Hopkins’s Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit.

Johnson, 39, is an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and probably the last person you’d associate with anything remotely psychedelic. Bespectacled and bearded, he has an earnest, reserved demeanor befitting a man whose CV is loaded with dense journal articles like “Replacing Relative Reinforcing Efficacy With Behavioral Economic Demand Curves.”

Johnson grew up in Landover, the son of federal employees. He began his academic career as a computer engineer but was drawn to psychology. “For me, it’s so obvious that understanding the mind and brain is the most interesting thing there is,” he says. “What could be more important?”

He earned a doctorate at the University of Vermont, where his dissertation was about the application of microeconomic theory to the decision-making processes of smokers—“Pretty nerdy stuff,” he concedes—and then came to Hopkins as a postdoctoral fellow in 2004.

Although his personal experience with addiction is limited to caffeine, he has spent much of his professional life teasing out its mysteries. “If you’re interested in understanding behavior, addiction is the big thing,” Johnson explains. “It’s behavior that’s stuck.”

“The answer to my needs was no longer ciagrettes,” one of Johnson’s subjects says. “Smoking became irrelevant.”

Hopkins turns out to be part of a burgeoning scientific renaissance of sorts. For decades, no human research was done with hallucinogens. Widespread recreational use in the 1960s and ’70s, some of it advocated by rogue researchers—remember Timothy Leary’s exhortation to “turn on, tune in, drop out”?—had rendered the drugs virtually radioactive to serious scientists. In recent years, however, researchers are creeping back out of the woodwork, intrigued by the insight hallucinogens may provide into the innermost workings of the mind as well as their promise of therapeutic applications.

“Sometimes I feel like Rip Van Winkle,” says Johnson’s postdoctoral mentor, longtime Hopkins professor Roland Griffiths, a co-investigator on the smoking study. “These drugs were thrown into the deep freeze, and they’re fascinating compounds.”

Griffiths authored a seminal 2006 study that ushered in a new era of psilocybin research. In it, an astonishing 67 percent of volunteers said that taking psilocybin was either the most meaningful experience of their lives or among the top five, an impression that held up even more than a year later. Additional studies are currently probing psilocybin’s potential to curb anxiety and depression in cancer patients and looking at how it may be used to jump-start or deepen a meditation practice. Other hallucinogens have also sparked renewed interest—as the author of the first human study on the psychoactive plant salvia, Johnson enjoyed a brief moment as a media celebrity when a video of pop star Miley Cyrus taking a bong hit of salvia went viral in 2010.

• • •

Johnson was intrigued by older studies that used hallucinogens to treat alcoholism and heroin addiction, and he wondered if psilocybin could help smokers who had repeatedly failed at quitting.

The connection is more intuitive than it might first appear. Psilocybin is known to induce transcendent mystical states virtually identical to those described throughout the centuries in religious and spiritual literature, and many addiction-treatment programs are rooted in some kind of spiritual epiphany. Bill Wilson, the cofounder of Alcoholics Anonymous, for example, quit drinking after an experience that involved seeing a bright light and feeling an overwhelming sense of freedom and serenity. There’s also anecdotal evidence that people sometimes quit smoking after recreational mushroom use.

“They’ll say, ‘Lo and behold, I had a cigarette in my hand and thought: What in the world have I been doing?’ ” Johnson explains. “Psilocbyin opens a window of opportunity with a very altered experience of oneself and of oneself in the world.”

Those mystical openings can elicit measurable differences in subjects’ behavior and personality, particularly in their acceptance of new ideas. The idea is to seize on that newfound perspective and to apply it therapeutically. The biological underpinnings of that change are still a mystery, but Johnson has recently partnered with the National Institute on Drug Abuse to conduct brain-imaging studies that might shed light.

Volunteers in the smoking study, which began in 2008, are carefully screened and prepared with several sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy; they might, for example, be told to visualize laughing, healthy lungs. They then undergo three daylong psilocybin sessions several weeks apart, though some opt to stop after the second session.

“For me, it’s so obvious that understanding the mind and brain is the most interesting thing there is,” says Johnson.

Johnson and his team have the sessions down to, well, a science—he authored a 2008 article in the Journal of Psychopharmacology on how to conduct hallucinogen research safely. The decor in Room 3102 might best be described as yoga-studio chic, with Tibetan peace flags and a Buddha statue. Tucked away on a bookshelf is a ceramic statuette in the shape of a cluster of mushrooms. The door is decorated with a print of an inviting path through a lush, wooded thicket.

Participants bring family photographs or other familiar objects to muse on. They lie on the couch wearing eyeshades, snuggled under blankets, and listen to a program of carefully selected tunes ranging from Brahms to Indian world music. Two trained guides provide support and reassurance; smoking is not explicitly discussed. A physician is always on call, though studies have repeatedly shown psilocybin to be physiologically safe and not habit-forming.

Exactly what happens on the couch is harder to explain. “You can’t really talk very intelligently about what it is you experience,” says Charlie Bessant, who tried hallucinogens as a college student in the ’60s. He throws out terms like “geometric connectiveness” and “resonant vibration” and says it felt a little like taking flight. “Everything is inside you, and you’re inside everything that surrounds you,” he says. He was overcome with a profound sense of gratitude for being alive.

Whatever happened during those seven or eight hours, the next morning Bessant’s urge for cigarettes was simply . . . gone. “The answer to my needs was no longer cigarettes,” he says. “Smoking became irrelevant.”

• • •

Outcomes like Bessant’s raise new possibilities in the war against cigarettes. Even the best smoking-cessation methods have limited efficacy; the drug Chantix has a success rate of less than 35 percent after one year and can have unpleasant side effects.

Of the first five participants to complete the psilocybin study, four weren’t smoking at all a year later and one had cut back to a single cigarette every two weeks. In all, 12 out of 15 volunteers—or 80 percent—were entirely smoke-free after six months. “That really blows out of the water what traditional treatment shows,” Johnson says.

“I’ve had colleagues who have studied some of the other techniques say, ‘I’ve never had five people in a row that have been this successful,’ ” Johnson says. He stresses the preliminary nature of these results as well as the tiny sample size. He also has no way of proving that it wasn’t the cognitive-behavioral therapy that did the trick. But Johnson is confident the results of this pilot are significant enough to shake loose funding for a full-scale clinical trial soon.

In other words, he’s clearly onto something, and with 19 percent of American adults still smoking, that something is desperately welcome.

“I don’t think we need something to get off smoking. What we need is something to stay off smoking,” says psychiatrist Herbert Kleber, the head of Columbia University’s Division on Substance Abuse and a former deputy director in the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy; he’s also a former two-pack-a-day smoker. “If this is a different mechanism and may lead to more prolonged abstinence, I think it’s worth a try. This is a very important addiction.”

Kleber emphasizes the need for caution when working with hallucinogens, a point to which Johnson is keenly sensitive. Despite the potential for punch lines about his work, Johnson takes pains to underscore its seriousness and safety.

“This doesn’t have a whole lot to do with someone taking mushrooms at a concert,” Johnson says. He likens it to the difference between receiving morphine in a hospital setting and seeing a heroin addict nodding off at a bus stop. Though the two situations involve similar substances, it’s all about the context in which they’re used.

Johnson, who is married and lives not far from his Hopkins office, declines to say whether he ever gave mushrooms the old college try: “We just don’t talk about that. Our research is not about the researchers. It’s about the volunteers and their experiences.”

• • •

Roland Griffiths of Hopkins acknowledges that hallucinogen research still carries some “cultural baggage,” pointing out that the psilocybin protocol was “reviewed more closely than any other I’ve been involved with in the 40-plus years I’ve been at Hopkins.” But Johnson denies having been hindered in any way, except to say that the National Institutes of Health has yet to provide any funding for research into the therapeutic use of psilocybin.

And while Johnson’s research veers into ethereal issues such as spirituality, he rejects the idea that there’s anything unscientific about it: “I take a very broad view. I don’t think anything is outside the realm of science. Science is a certain manner of addressing questions. The heart of that is empiricism, testing questions. It doesn’t matter what questions you bring to that.”

Johnson and his colleagues have a guarded optimism about psilocybin’s potential to help with smoking, other addictions, and mental-health problems. “I don’t ever anticipate psilocybin treatment being ‘take two of these and call me in the morning,’ ” he says. Instead, he could see the treatment being done in a specialized setting similar to that for outpatient surgery. And he says the lessons learned from hallucinogen research may lay the groundwork for one day allowing people to have the same kind of transformative experience—using something like breathwork or meditation—without any drugs at all.

“We’re on the verge of uncharted territory,” he says, a tinge of excitement in his normally steady tone. Particularly intriguing is the idea that hallucinogens might have psychological and behavioral effects long after they’re gone from a user’s bloodstream, a possibility that would fly in the face of all that traditional psychopharmacology has taught.

“That’s very much outside the box,” Johnson says. “The word ‘paradigm’ is overused, but this work is introducing a new paradigm in medicine.”

Jennifer Mendelsohn (mendelsohn.jennifer@gmail.com) is a writer in Baltimore whose work has appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, People, and Slate.

This article appears in the January 2014 issue of Washingtonian.