Leon Panetta has a great story about Cami McCormick, from a trip to Afghanistan, ten days before Christmas 2012. McCormick, a radio correspondent for CBS News, had been sent to cover the Defense Secretary’s final visit to Afghan president Hamid Karzai. After trudging across snow and, more precariously, the palace’s polished marble steps with one prosthetic leg and the other painfully braced from shin to heel, she arrived inside the palace to be told that her prosthesis had to be removed so it could be cleared by a bomb-sniffing dog.

McCormick asked that the dog be brought to her. “We can’t do that,” the Afghan guard said. “You’re a woman.”

McCormick composed herself and stripped off her leg, handing it to the guard, who clutched the correspondent’s cane under his arm. “Why don’t you walk with me now?” he asked as he headed off, her limb held over his head like a bowling trophy.

“That was the second time an Afghan took my leg,” she says with a grin.

When Panetta heard about the incident, he was furious and approached McCormick to ask how she had retrieved her leg. “A whole lot of F-bombs bouncing off the marble walls,” she told him.

“That’s his favorite part of the story,” she says.

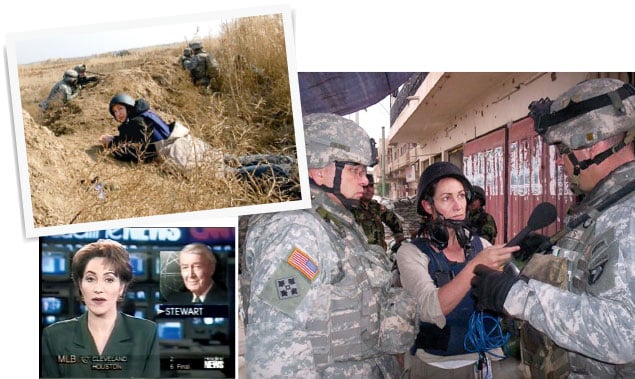

McCormick, 52, has spent countless months reporting from Iraq and Afghanistan since 9/11. War zones have become her natural environment. Landing in Kabul with Panetta, she was less worried about mortar strikes or suicide attacks—though on Panetta’s previous arrival in Afghanistan, an insurgent set himself on fire and drove a truck toward a line of officers waiting to greet the plane—than about the seas of gravel outside official buildings and the steep ramps of military aircraft.

McCormick’s difficulties with terrain the rest of us consider manageable is one more thing she shares with battlefield veterans from the past decade. Like many of them, she took a ride in a convoy in Afghanistan and woke up in the United States with a piece of her body missing.

• • •

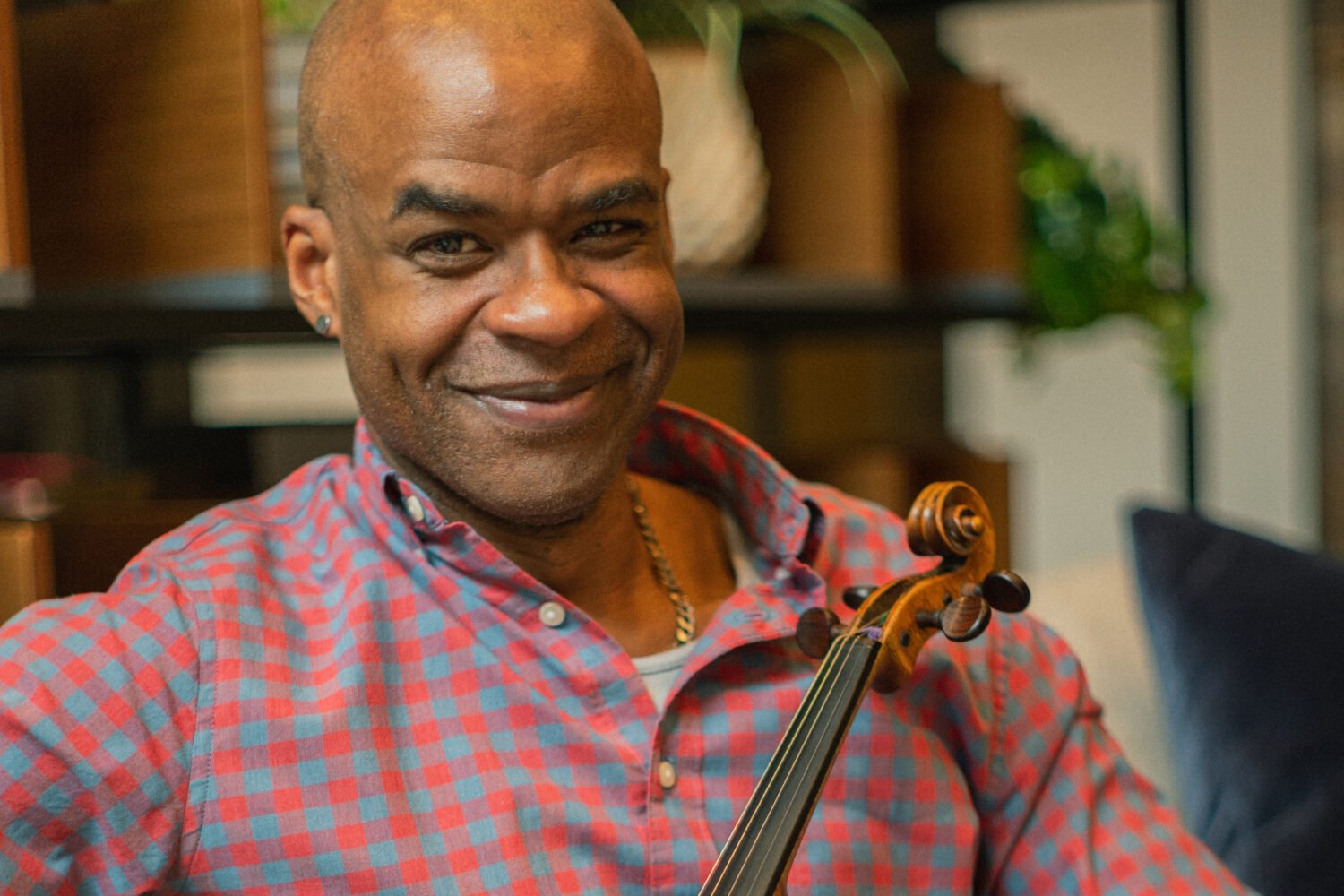

From head to artificial toe, McCormick wears black—black sweatpants and black shirt, soaked through with sweat. Wide black boots fit her inflexible foot and the extra width of her brace. On this day, she has just finished two hours of intensive rehabilitative therapy, which she gets as an Army Secretary designee, allowing her access to the same care and prosthetics as wounded soldiers. (The designation only grants her the care; CBS pays the bills.)

Outside the therapy room is the enormous lobby of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda. Staff in scrubs and patients walk briskly past an obsidian-black baby grand piano where a wounded soldier plays Gabriel Fauré’s “Pavane in F Sharp Minor, Opus 50.” No one is there to sing its melancholy lyrics: Et c’est toujours de même, et c’est ainsi toujours! (And it’s always the same, and it’s this way forever!)

Nearly five years after her injury, the hospital is still a second home to McCormick, who moved to DC’s Friendship Heights in 2011 from New York to be closer to the hospital. She has become close with several fellow amputees, whom she calls “the guys,” dishing out tough love to some like a mindful aunt. Though she’s typically three decades older, a woman, and a civilian, the soldiers seem to make no distinction between her injury and their own. “When I was in Iraq and the guys would get into a gunfight or someone would get hit,” she says, “they were a lot more open with me. I wasn’t such an outsider anymore.”

“She’s part of the group now,” says Sergeant José Ramos, who was with her the day she was hurt. “When bullets start flying and you survive, that’s a brotherhood that never dies.”

• • •

McCormick arrived at Walter Reed the same way most of the soldiers did, in a frantic journey that began August 28, 2009, in Afghanistan’s Logar Province, a sparsely populated region near the Pakistan border veined with marijuana fields and steep valley walls that make it perfect territory for ambushes.

That day, a week after Afghanistan’s first round of voting for president, McCormick was riding with the 10th Mountain Division in the Charkh District. She was offered a spot in one of two vehicles: a 14-ton MRAP, an armored vehicle that looks like a giant safe on wheels, or a smaller Armored Security Vehicle (ASV). “Which one is safer?” she asked the convoy’s commander.

“Well, it depends on which one gets hit, doesn’t it?” he deadpanned. McCormick had never ridden in an ASV, so she jumped in.

The explosion that came a short time later corkscrewed the 29,000-pound vehicle off the ground. The force of its landing popped all four tires. Ramos, who was in a following vehicle, rushed to the ASV to sweep for survivors. He found the rear doors blown apart and Specialist Abraham Wheeler III—a 22-year-old from Columbia, South Carolina—dead in the turret. Ramos dragged Wheeler and McCormick away as ammunition rounds in the truck cooked off and exploded. He laid a poncho over Wheeler and tried to calm McCormick, who was in and out of consciousness, until a helicopter arrived to take her and Wheeler to Forward Operating Base Shank, a few miles away.

“I’ve been told I said a few things after that, but I don’t even remember,” McCormick says. “The first was ‘It isn’t anything a cigarette and a glass of whiskey can’t fix.’ ” She laughs. “The other thing I said to al-most everyone in between Afghanistan and Walter Reed: ‘Please don’t let them take my legs.’ ”

Told by CBS that McCormick was alive but seriously wounded, her sister, Kelli McCormick, arrived at Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany expecting to find that Cami had broken a few bones. “You get to a point where you invent things to get through the day,” Kelli says. “She’s a girl and works for CBS. What’s really going to happen?”

Kelli had brought along her daughter, Susannah, who often traveled with McCormick and who once helped escort her aunt home from a family trip to Alaska after McCormick fractured her ribs in a dogsled accident. Instead, Kelli and Susannah found Cami in a coma with two badly damaged legs.

• • •

A week later, still in a coma (but with her legs expertly shaved at her nurses’ insistence), McCormick flew home to Andrews Air Force Base. Inside the transport plane—Kelli likens it to a flying Walmart with blacked-out windows—Kelli and Susannah strapped in beside a wounded Army sniper who talked endlessly about the McDonald’s burger waiting for him. They ended up sleeping on the floor where McCormick, flanked by three attendants, lay on a stretcher.

At Walter Reed, she was brought out of her coma, but in her anesthetic haze she believed soldiers were infiltrating the hospital to kill her. When Kelli hung family pictures by her bed, McCormick demanded she take them down, saying, “We’re all in danger.” She woke from a dream thinking Marines were hacking her computer to expose a source and had erased all her e-mails and contacts.

Kelli found out her sister’s leg needed to come off before Cami was told. “She wants to wear sandals,” Kelli protested to the doctors. “I wanted her to hold out as long as she could,” she recalls. Kelli demanded an orchestrated presentation of all the options with a host of physicians, “so it wouldn’t be out of the blue,” she says. When one doctor clumsily let the word “amputation” slip, Kelli went into a rage in the hallway. “But I was the one who didn’t get it,” Kelli says. “Cami wanted to get back to it. Lying in bed helpless—that wasn’t her.”

Growing up in Tennessee, McCormick had always been a restless sort. “Cami has a problem with daydreaming,” her first-grade teacher in Murfreesboro wrote on her report card. “And staring at the maps on the wall.”

As a communications student at the University of Southern Mississippi, McCormick says, she learned the ropes of radio while working at a local station, honing a voice that’s not quite masculine but more sober than a typical female pitch. Hired by a station in New Orleans in 1987, she began making trips at her own expense to Northern Ireland and the former Soviet Union, looking for bigger stories, and in 1991 she helped launch Moscow in the Morning, one of the first English-language news programs in Russia. She covered the Good Friday peace accords in Ireland for CNN and the Israeli incursion in the West Bank after moving to CBS, which sent her into Iraq the day after Saddam Hussein’s statue was toppled in Baghdad.

• • •

Reporters have been covering war for as long as writing has existed, but lately the cost has grown. In the past two years, 253 journalists have been killed on assignment, according to the International Press Institute. Statistics on those who come back are more elusive. War transforms those who fight, but it often does the same for those who bear witness.

When the Washington Post’s military writer, Greg Jaffe, started on the defense beat in 2000 for the Wall Street Journal, he mostly documented the military’s high-tech initiatives to keep boots off the ground. Four years later, Jaffe found himself in a Humvee in Ramadi, Iraq, his feet planted on sandbags to slow deadly shrapnel from roadside bombs. From 2003 to 2012, he spent two months of every year as an “embed.”

The hardest part was the transition from Iraq to stateside. “I remember thinking this was important work and I shouldn’t be going home,” he says. His wife noticed he dealt with setbacks more erratically. “Stress would spike on the embeds,” he remembers, “but back home it never went down to zero.” Home full-time now for almost two years, he feels like he’s missing a story.

For McCormick, the transition has been slowed, like everything else, by her injury. She covers the State Department—recently following Secretary of State John Kerry to Ukraine, Jerusalem, Moldova, and Belgium—and the Pentagon, whose endless, mazelike corridors she navigates with her cane. “Before I was injured,” she says, “I’d wake up and think about the stories I was working on or places to find new ones. Now I get up in the morning and think, ‘This shower is going to suck.’ ”

Her assignment in Ukraine in March was her first outside the State Department’s security strictures. The steep cobblestone roads around Kiev’s Maidan, the square where demonstrators rallied, were exhausting, but she was energized by the freedom to report: “It was great to be on the ground and get to know the people, instead of flying in and out. It made the story better.”

But the reality of her condition sets in as she discusses her future. Her braced right leg isn’t healing, and amputation is always a possibility. McCormick has seen many double amputees and knows walking would require learning a completely different calculation of dexterity.

All the more reason to work harder now. “Every time I finish a trip, I’m proud of myself,” she says. “They love it at Walter Reed when I come in and say my knee is killing me because I had to jump on and off helos. There are hundreds of people who worked so hard to get me this far. So what am I going to do—go sit behind a desk?”

At some point, traveling the world on a prosthetic (or possibly two) will be unsustainable. McCormick figures she’ll leave journalism then and open an animal refuge, maybe in California—possibly the farthest anyone could be from a war zone, both in body and spirit.

“One day, maybe,” she says. “For now I’d rather worry about how I’m getting on this helicopter.”

Alex Horton (alexehorton@gmail.com) is a freelance writer whose work has been published on TheAtlantic.com, ForeignPolicy.com, and The New York Times blog At War.

This article appears in the July 2014 issue of Washingtonian.