About Saba

When he arrived in the US from Yemen 15 years ago on a student visa, Taha Alhoraivi was so ignorant of his culinary tradition that he didn’t know how to make a single dish. Cooking was women’s work, according to his mother and sisters.

“I could boil an egg,” he says.

Daydreaming in his Long Island University business-administration classes about the rich, aromatic stews he was raised on, he’d return at night to the cramped Brooklyn apartment he shared with two cousins to dry, colorless meals of eggs, bread, and cheese. Eventually he grew desperate, and on his first trip back home he beseeched his mother and sisters for recipes.

Thus began a slow, fumbling process of experimentation and research as he sought to recreate, in isolation, the tastes of memory.

The culmination of that 15-year journey is Saba, the remarkable restaurant that Alhoraivi, an erstwhile manager at Pizza Boli’s, opened three months ago in a Fairfax strip mall, having decided to turn his culinary “hobby” into his profession and set about showing his adopted city that there’s more to Yemen than civil war and drone strikes.

At first glance, Yemeni cooking bears obvious similarities to that of Lebanon, Morocco, and Egypt. Lamb and yogurt and honey are foundational elements, the spice box (cumin, clove, cardamom) is liberally employed, and stews predominate. But there are distinct and sometimes fascinating differences.

In a single meal, you might eat wheat bread, pita, and even injera (the last is the basis of a refreshing dish called shafoot, in which the spongy Ethiopian bread is doused with cilantro-flavored yogurt and sprinkled with diced radish and tomato). You’ll almost certainly eat a lot of rice, so integral to the Yemeni table that Alhoraivi makes a fresh batch every half hour.

His richly detailed preparations may well change the way you view the grain. Witness the preparation of haneeth, a traditional feast-day dish of slow-cooked lamb over spiced rice. The leg meat lifts away from the four butchered bones with minimal prodding, but the rice is the revelation—each grain distinct; subtly perfumed with cardamom, cumin, and cloves; and infused with both the juices of the meat and its sweet-savory sauce.

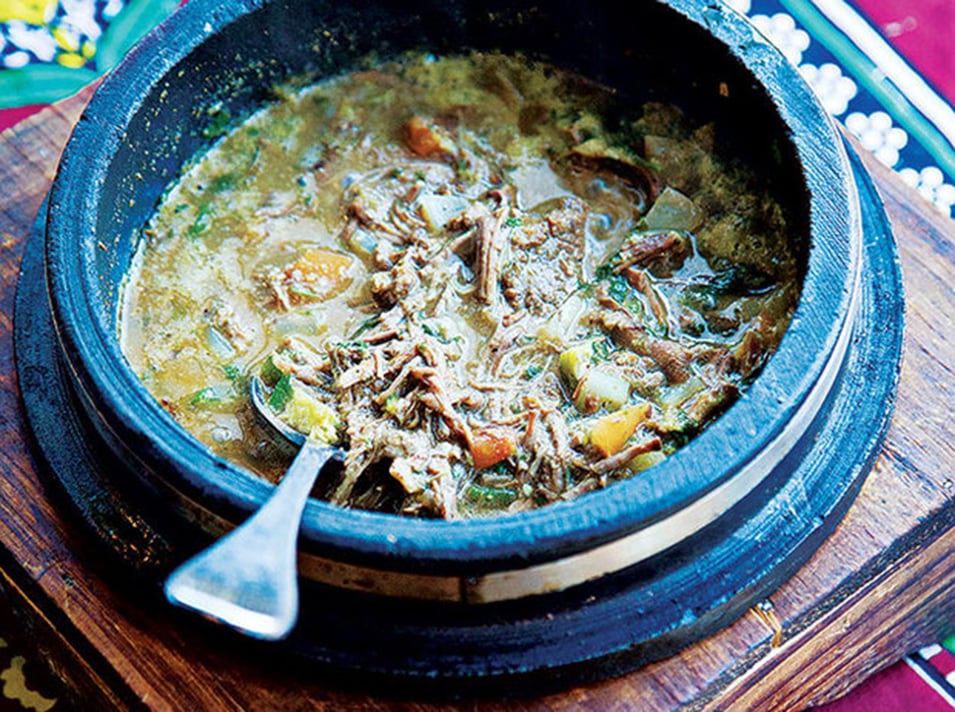

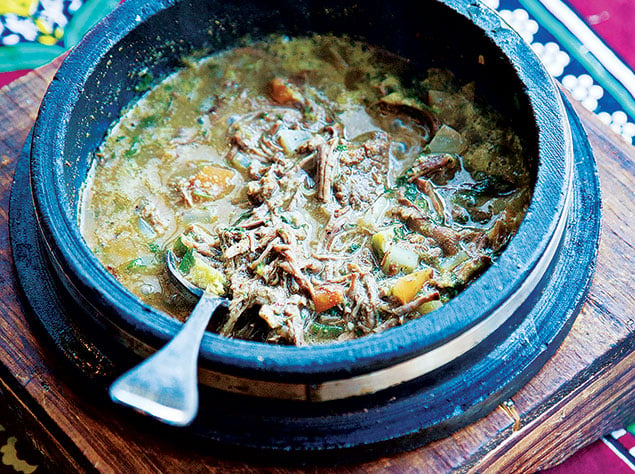

No dish illustrates the slow, steady marriage of flavors over a period of hours quite like the fahsa, a bubbling cauldron of shredded beef in a cumin-laced tomato sauce so concentrated and rich it might as well be a syrup. Alhoraivi gives it a dollop of hilbeh, a slightly sour dip flavored with cilantro, jalapeño, and mint that adds cool to hot, brightness to richness.

All the desserts, including baklava and basbousa, a honey-drenched semolina cake, are made daily and are worth your time. The tour de force is the masoob, a sweet and savory bread pudding that’s started early in the morning, when Alhoraivi bakes several wheat loaves. Each bite seems to turn up something different: a taste of caramelized bananas, of honey, of cream, of nigella seeds.

The chef’s discovery becomes, happily, our own.

This article appears in the November 2014 issue of Washingtonian.

100 Very Best 2015

100 Very Best 2015 Eat Great Cheap 2015

Eat Great Cheap 2015