Tarek Elgawhary remembers noticing the blue COEXIST bumper stickers on the Clara Barton Parkway three years ago while driving from his Potomac home to his office in Georgetown. Raised in Gaithersburg, Elgawhary had been in Cairo when the sticker’s jumble of religious iconography—the C a Muslim crescent, the X a Star of David, a Christian cross for the T—spread across post-9/11 America’s bumpers.

The sticker was a little granola for his taste: He often saw it crowded next to a peeling NADER OR PRESIDENT and almost always, he recalls, on a Prius. But Elgawhary, CEO of the Coexist Foundation—which works to bridge cultural divides by promoting understanding—agreed with the sentiment. What’s more, he saw an opportunity. There, on hundreds of cars, was a ready-made advertisement for his organization.

So like any sensible businessman, Elgawhary tracked down the man who owned the rights and licensed it.

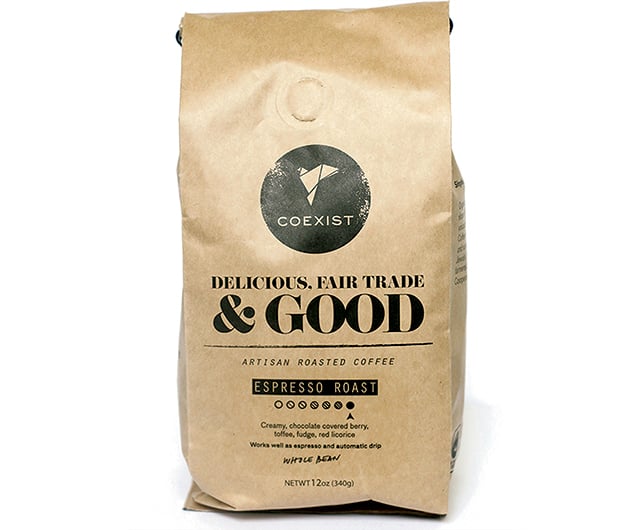

The Coexist Foundation now hawks the blue stickers for $10 on its website, under “swag,” along with bumper magnets and window decals; a coexist guitar decoration is $5. Elgawhary admits he doesn’t sell many stickers, but owning the design is great branding for Coexist’s more profitable businesses—shade-grown coffee raised on a farm in Africa and organic clothing manufactured in India. Wherever he goes, says Elgawhary, strangers already have an idea of what Coexist stands for. “They’re like, ‘Oh, you’re the bumper-sticker people!’” Since buying the design, he simply says yes. “That’s worth its weight in gold.”

It would be easy to mistake 35-year-old Elgawhary, who talks with ease and purpose, for an entrepreneur. A polished speaker with a communications background, the philanthropist likes to name-drop, mentioning he’s been chatting with Madonna’s charity advisers or that Ashton Kutcher name-checked his bumper sticker on Two and a Half Men.

Elgawhary is one of a growing class of business and charity leaders pushing a generational change in how philanthropy works. Armed with business savvy and a guiding social conscience, organizations such as Coexist blur the line between foundations and corporations, selling products and services to benefit not shareholders or investors but the greater good.

“These organizations aren’t located squarely within the nonprofit, for-profit, or public sectors,” says Nathan Dietz, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute’s Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy, in DC, who calls this domain the “fourth sector.” He and his team recently began a Fourth Sector Mapping Project to identify and characterize the range of these hybrid organizations.

Last June, Coexist formed a partnership with Peace Kawomera, a ten-year-old cooperative of 2,500 Ugandan coffee farmers who needed a bigger market for their product. Coexist now imports the cooperative’s coffee beans to the US, where it produces light, dark, and espresso roasts and sells them on its website. In keeping with the organization’s mission, the profits go back to the community’s primary and high schools, near the coffee growers in Mbale, a town by the Kenyan border. In a country with delicate relationships among religious groups, the schools accept students regardless of religion, furthering the community’s real coexistence.

Social enterprise has existed in some form for more than a century. In 1902, a Methodist minister in Boston founded Goodwill Industries to hire poor workers to repair and sell household goods. Actor Paul Newman and his screenwriter friend A.E. Hotchner introduced the idea of charitable consumption to grocery shelves when they began selling Newman’s homemade salad dressing and giving away the proceeds. Since then, Newman’s Own has donated more than $380 million from its sales of salsas, popcorn, and pizza to various charities. Newman’s daughter runs an organic-food offshoot.

But in the past few years, social enterprise has come to describe a way of doing business on either side of the for-profit/nonprofit line, and new terms like “for-purpose” corporations have cropped up to describe them.

For millennials especially—who share snapshots of their lives on Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr, and other social-media platforms—spending has become a form of self-expression and brands are expected to reflect moral values as much as economic status. “They think, ‘I was going to buy that shoe, I was going to buy that cup of coffee,’” says Jeff Fromm, a marketing expert who follows the millennial generation’s proclivities, “‘and now there’s a company that believes what I believe, that will allow me to feel better about myself because I chose their brand.’”

Companies such as the hipster eyeglasses purveyor Warby Parker and the shoemaker Toms meet this desire by paying customers’ purchases forward, donating shoes or discounting eyewear for the needy in the Third World. A Pennsylvania nonprofit, B Lab, helped states develop a certification known as a Benefit Corporation—akin to an environmentally sustainable building’s LEED wall plate—which declares that it’s meeting social standards.

In 2013, Aloetree, a company that makes organic clothes for babies and kids and donates 50 percent of profits to stop child trafficking, became DC’s first Benefit Corporation. Founder Anbinh Phan is a Vietnamese refugee whose family emigrated to the US when she was a year old. An economist and lawyer, Phan designed the cartoon animals featured on her clothes, found a manufacturer in India, and sold her first items from a stall at Eastern Market a little over a year ago. Today her line is sold at Georgetown’s Dawn Price Baby and other local boutiques.

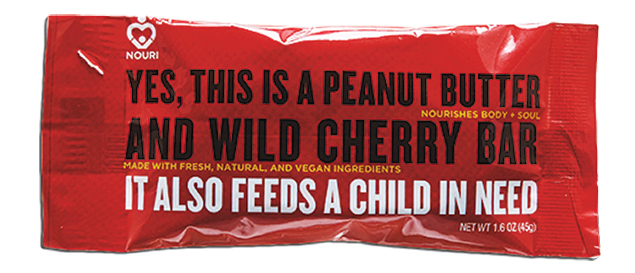

For some, the narrowing distinction between charity and business has made the choice of livelihood simpler. “I was torn between wanting to go into nonprofits and wanting to work in the business world,” says Veneka Chagwedera, who grew up in Zimbabwe. When her peers were young, they were often taken out of school to earn money for their families. As she studied at Princeton and later at the University of Virginia business school, Chagwedera felt a responsibility to take on the problems that had deprived many of her former schoolmates of an education.

For years, Chagwedera had made her own nutrition bars, mixing ingredients from farmers markets and local shops in a tiny Cuisinart food processor. One night as she was talking about her future with her husband, Jared Crooks, Chagwedera looked down at the bar she’d been snacking on. “That’s when the idea hit me: What if I can combine the two?”

After UVA awarded Chagwedera and Crooks a spot in the business school’s incubator program, they moved the manufacturing out of their kitchen and began to work with Stepping Stones International, a nonprofit in Botswana that provides meals to hungry kids. By 2012, Nouri bars were on the shelves of Whole Foods and furnishing a meal for a child for every bar sold.

Since then, Nouri has expanded beyond Africa to Guatemala, the Philippines, Haiti, and the United States, calculating the local cost of meals from the United Nations’ World Food Programme estimates and donating quarterly to Stepping Stones and other anti-hunger agencies.

Social consciousness isn’t without its bumps. Another snack-bar company, Kind, has struggled to find a workable method to encourage random acts of kindness, including an online good-deed registry that turned into “a logistical nightmare,” a spokesperson told Fast Company magazine in 2012. Now a network of Kind team members give away cards redeemable for free bars to people they see being nice, and each month the company donates $10,000 to a cause its customers recommend.

Coexist’s model—like Aloetree’s, which integrates its giving into its business—doesn’t have to build a separate system to get consumers to contribute. “Whether or not they know, they’re helping,” says Phan. And rather than maximizing profits and giving away a portion, as many businesses do, the nonprofit companies are better able to represent their values at every point of production.

Another advantage, Chagwedera notes, is the consistency of the funding. Unlike groups that rely on corporate or personal donations, which tend to taper off when times are tough, the meals children get from Nouri’s profits are “something that they can depend on.”

Indeed, according to Darius Graham, founder of the DC Social Innovation Project—which helps kick-start projects that tackle social issues in the District—the social-entrepreneurship movement got a boost from the 2009 economic downturn, when many traditional charities were forced to seek out revenue independent of donors’ disposable incomes. “Organizations that wanted to make a difference had to think more creatively and strategically about how they’d do that,” says Graham.

It was such a lack of funding that led Tarek Elgawhary to start selling clothing and coffee. Early on, Coexist, founded by three London businessmen in 2006, had operated as a traditional foundation, handing out grants for religious-literacy projects. But as it grew, the trustees, who funded many of the grants out of their pockets, began to look for more viable long-term funding.

When Elgawhary became CEO in 2012, he was determined to find a way to make giving easier. He struck upon the idea of making people consumers of philanthropy, and it became his holy grail.

The answer came from an unlikely source.

Twelve years earlier, Elgawhary had just started medical school at George Washington University when three planes flew into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. He didn’t think studying to be a doctor could do enough to ease the sudden climate of intolerance—much of it geared toward people of Middle Eastern descent like him. Though he’d been raised in Gaithersburg, Elgawhary found himself constantly explaining his identity to his schoolmates: how to pronounce his name, why his parents, immigrants from Egypt, spoke with accents.

In grade school, his teacher gave his class the option of making either a Christmas tree or a menorah out of construction paper. Elgawhary, remembering happily eating watermelon on a visit to Cairo, instead picked that. Tacked on the classroom wall among Christmas trees and menorahs, his red-paper watermelon slice singled out his otherness.

After 9/11, the divide he had felt while growing up was now the world’s leading issue. “I wanted to do something to solve this problem,” he says.

He enrolled in a master’s program in Hinduism and Islam, and a year later he was studying at a seminary in Cairo, where he met Sheikh Ali Gomaa, who soon became Egypt’s grand mufti, a high-ranking Muslim official in the country. Gomaa was a hugely influential figure in the broader Muslim world. Gomaa appointed Elgawhary to handle the leader’s international communications.

In 2006, Gomaa was invited to a meeting in London with three businessmen—an Australian, a Brit, and a Saudi. The three had been called to action by a Gallup poll that found a gap in understanding between Muslims and the West. They’d started Coexist to change that and sought to bring in Gomaa, along with high-profile Christian and Jewish religious leaders. Elgawhary became the liaison between Coexist and the grand mufti.

Eventually, he moved back to the States to resume his religious studies at Princeton, but he began working for Coexist in its New York branch. Six months later, the CEO stepped down and Elgawhary was offered the job. (Shortly afterward, he relocated Coexist’s US headquarters to Washington.)

When Elgawhary floated his idea to switch to a business model, his primary influence wasn’t Coexist’s businessmen founders. Instead it was inspired by his mentor, the grand mufti.

“He insisted on adding the commercial component,” Elgawhary says. “‘You have to use an economic incentive,’” he recalls his mentor telling him, “‘to get people to coexist.’”

Rebecca Nelson (rebeccarosenelson@gmail.com) is a staff correspondent at National Journal.

This article appears in the February 2015 issue of Washingtonian.