Nadine, a 48-year-old aerospace engineer turned investment manager in Northwest DC, has two Ivy League degrees and an MBA from Stanford. She’d succeeded at pretty much everything she tried in life—and then she had kids. Her daughter, now six, and her son, eight, fought constantly, and her daughter, to put it bluntly, drove her crazy.

Mostly, it was the nonstop tantrums. From infancy on, the little girl would wake up screaming every morning. She refused to go to sleep alone. Though she generally kept it together at school, the minute her mother arrived to pick her up, the outbursts began anew.

“I completely dreaded the weekend,” Nadine says. “I would think: Oh, my God, it’s Friday—is there more work I can do just to avoid this unstructured time, this ‘quality time’? And then I would count down till Monday.”

Concerned about an accident, Nadine started driving with earplugs. Still, there were some perilous moments on the road. Once, her daughter unbuckled her car seat, lunged forward, and started pulling Nadine’s hair until she thought her scalp would bleed. On another occasion, the girl reached out while Nadine was parking and yanked at her necklace so forcefully that it broke.

“I started choking,” she says. “I knew she wasn’t going to strangle me, but it was scary.” No less mortifying: the passer-by who clucked at her predicament.

It didn’t help that Nadine felt completely on her own. Her real-estate-developer husband would vanish to some other part of the house, she says, or gravitate toward their easier child. No one else’s kids seemed to behave like her daughter; friends didn’t seem to believe her horror stories. And the little girl’s doctor said there was nothing clinically wrong with her. She was just a handful.

Nadine coped at first by outsourcing childcare around the clock—a nanny for the workdays, a rotation of babysitters to help out when she was home. She read the classic 1995 primer 1-2-3 Magic: Effective Discipline for Children 2-12, but the tantrums didn’t subside. Once, during a particularly violent shrieking episode, she was so desperate she called 311 and begged for help. The operator eventually got on the phone with the girl and talked her down.

In the end, Nadine turned to the parenting website DC Urban Moms in search of a specialist and came across descriptions of one who sounded like the answer to her prayers: Dr. Dan Shapiro. His highly in-demand Rockville practice was closed to new patients, but she learned about a group class he taught, called “Raising Your Challenging Child.” She registered on the spot.

Three months later, Nadine finished the course with a completely upended understanding of how to parent. “I learned to be much more empathetic,” she says. “Instead of yelling at my kids to hurry up, I started to kneel down and put my hand on their shoulder and say something funny like ‘Mars to Earth, come in.’ Just that one technique made a huge difference.”

Her daughter has quieted down to a degree Nadine didn’t think possible, and while the girl’s behavior is far from perfect, it’s much more manageable. Nadine says she’s grateful to Shapiro for “putting me on the right path. He made me feel there was hope. And I started by fixing the small things.”

Today, parents like Nadine speak of Shapiro in reverential terms—more as if he’s a shaman than a physician. To them, he’s the child whisperer.

Shapiro, for all his talents, also represents a fascinating example of a wrinkle in the Washington area’s otherwise saturated market for parenting-assistance services. The 57-year-old, cardigan-wearing MD with a Mister Rogers vibe, whom fans call Dr. Dan, practices developmental and behavioral pediatrics. It’s a relatively new specialty that focuses on behavior, and one that’s increasingly in demand. Families seek out Dr. Dan for help in dealing with all kinds of kids—the developmentally challenged and the merely challenging. Many pay heftily, about $325 an hour, for his services. If they can get in, that is. He says new parents try every day.

But with a patient roster that numbers in the hundreds at any given time, his practice is perennially full. Hence, the group classes—which is where I met Dr. Dan and learned firsthand that the hype isn’t unfounded.

Over the course of ten weeks, Dr. Dan unfurled a series of simple techniques that, while not always intuitive, are eminently doable, tricks that even the most overwhelmed parent can easily practice, if not master. Which, he insists, is okay. “I want to give people more comfort about seeing to their own needs, and not just trying to be a perfect parent but trying to be real,” he says, “and being okay with being the so-called good-enough parent.”

When I arrived at a church in Tenleytown for my first class one night last fall, some 60 people were already assembled. At 7:30 sharp, the session began with Dr. Dan asking why we’d come. Just like that, hands shot up and the roomful of parents began confessing their troubles with surprising candor:

My kid loses it every time I ask him to get dressed in the morning.

My kid is an angel at school and a nightmare at home.

My kid ruins every vacation.

I can’t go to Target without a major freak-out.

My life as a parent is just way more difficult than I thought it would be.

The whole scene felt like an upscale AA meeting (there was even a table near the entrance with an oversize coffee urn), where you came to be heard as much as to be helped.

“I felt like I’d found my people,” a mother of two named Christina told me of the first class she attended.

“I finally knew that I wasn’t alone,” said Chelsea, whose eldest child has ADHD. “I’m not the only one who has a panic attack when the phone rings and I see that it’s Montgomery County Public Schools.”

Presiding over this fellowship wasn’t necessarily part of Shapiro’s career plan. He grew up in East Lansing, Michigan, and came to DC for med school at George Washington University. After completing his residency in 1985 at what’s now Children’s National Health System, he worked as a general pediatrician, treating the usual strep throats and chicken pox. But 12 years in, he had the first of five operations on his neck, fallout from a condition he attributes to “bad genes and an occupational hazard of pediatricians. A lot of us have back problems because we are stooping over little kids all day.”

After his surgeon forbade him to do any more physical exams, Shapiro was forced to rethink his professional trajectory. One day in 1999 while recovering from one of his surgeries, “I called my office manager and said if anyone wants to come out to the house and just talk, I’m sitting here in my living room.”

The answer was yes, definitely. In an era of rushed annual checkups, the idea of sitting down with a pediatrician who actually had time to spend talking through a child’s developmental issues had clear appeal.

Even if his spinal column brought it about, Shapiro turned out to be not at all unsuited for this sudden career change. He’d always been interested in child development. For years he’d been bookending his workdays with an hour when families could come by just to talk. But Dr. Dan also benefited from some lucky timing—1999 was the same year that the American Board of Medical Specialties approved the new subspecialty of developmental and behavioral pediatrics. And as he soon saw, parents were desperate for this type of doctor. “Right away,” Shapiro says, “I was busier than I’d ever been.”

With fewer kids dying in early childhood, the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1993 had urged doctors to pay more attention to developmental problems—what had become known as “the new morbidity.” In 2001, the AAP again called for a “renewed commitment to the psychosocial aspects of pediatric care.” In the ensuing years, doctors have become more adept at identifying autism, ADHD, and anxiety, the most common childhood psychological disorders. And that spike in diagnoses has correlated with a demand for people like Shapiro.

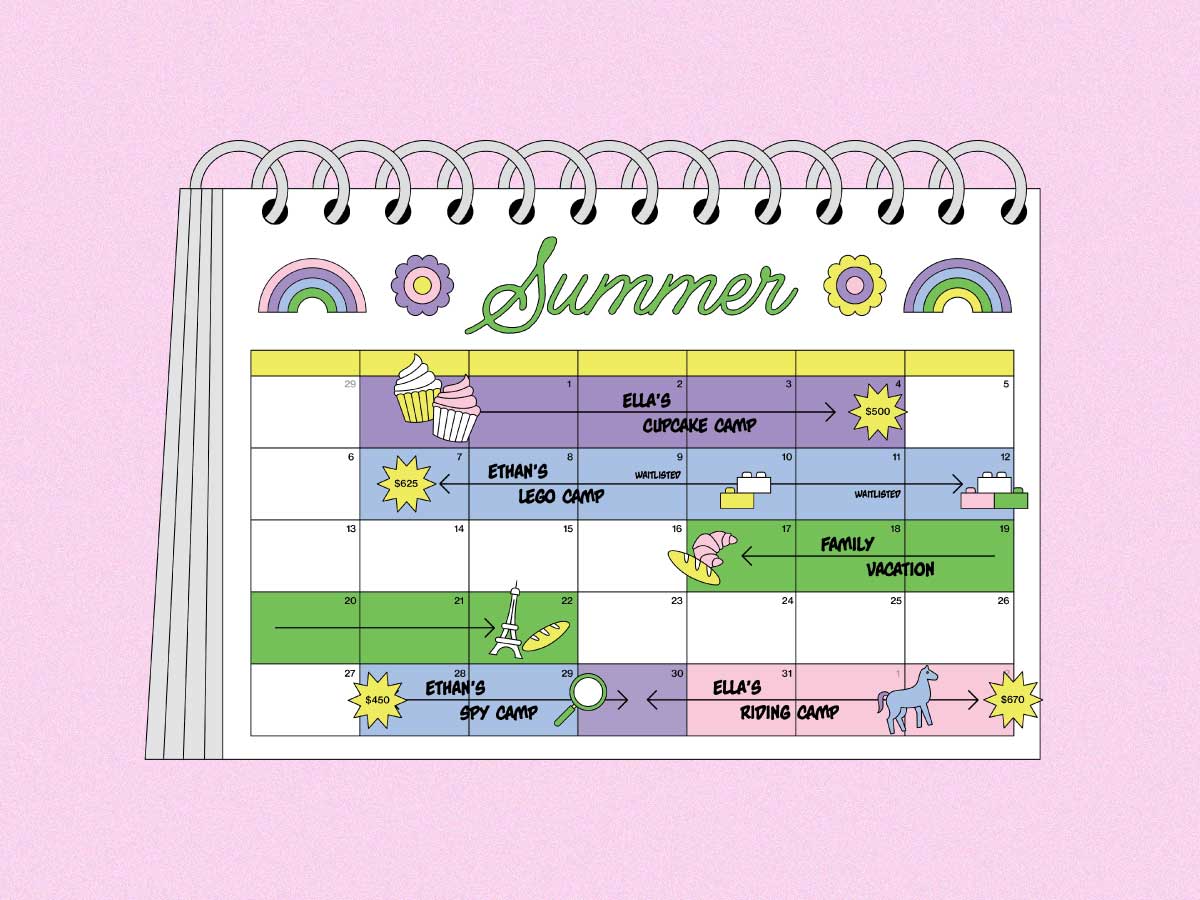

The job, he says, is “a mismash of general pediatrics, social work, psychology, special-ed advocacy.” It’s intensive. Shapiro manages kids’ medication and coordinates care with other specialists. He helps families choose schools, sits in on IEP (individualized education program) meetings, and advises families on which extracurriculars kids should pursue, even how they should spend their summers.

A father of four himself and a man with eclectic talents (he unicycles and plays the guitar), Shapiro has an unusual and, to many parents, wholly reassuring manner.

“My younger kid had just gotten a harmonica, and he came into Dr. Dan’s office with it,” Christina remembers. “He was so excited to play something for Dr. Dan, and when he was done, Dr. Dan got out his harmonica and did this full-on, foot-stomping routine. My son was just blown away.”

Because he believes in early intervention, Shapiro takes new patients only under age four. Many stick with him through high school.

Yet, he says, “for every school consultation I do, I see two or three other kids in the classroom who have something going on, and the teachers come up to me and say, ‘By the way, while you’re here, would you mind looking at this kid, too?’ ”

Therein lies a peculiar market paradox endemic to Washington. The area is medically rich—it’s teeming with doctors—but by Shapiro’s estimate there are only about a dozen developmental pediatricians. Most are expensive, and almost all have closed practices or lengthy waiting lists. “We are as fortunate here as anywhere,” he says, “and it’s still nowhere near where it needs to be.”

One big reason, he says, is because when doctors enter med school, they tend to have a “diagnose-and-fix-it mentality,” while developmental pediatricians must by definition take a longer view. Another reason: With the around-the-clock phone calls, e-mails, and detailed report-writing the job entails, it’s often more labor-intensive and less profitable than the glitzier, instant-gratification-oriented specialties of, say, the plastic surgeons Washington has in abundance.

Shapiro had taught some form of parenting classes for years, but the daily stream of requests from distressed parents, many with kids over age four, prompted him to teach a class that focused on behavior challenges. Four years ago, a psychologist named Sarah Wayland secured a grant to help him bring it to Prince George’s County on a pay-as-you-can basis.

“Much to my amazement,” Shapiro says, “the group I was offering to 10 or 12 people at a time for a substantial sum of money now had 85 or 100 people in it.” He was also taken aback at how attendees “felt more comfortable in large groups—they felt strength in numbers.” When he moved the classes (now also taught by Wayland) back to Northwest DC and Rockville, he kept the pay-as-you-can pricing, and the supersized crowds kept coming.

I signed up for Dr. Dan’s class because my son wasn’t outgrowing his tantrums the way all his teachers (who never had the pleasure of witnessing them) assured me he would. He would just “snap out of it,” they said—but when exactly? If, as the handful of expensive experts I’d consulted promised, there was nothing “wrong” with him, why was every minute of every day harder than it should be?

Nothing we tried—endless time-outs and withdrawn privileges, enough sticker charts to paper the Pentagon—seemed to work for more than a couple of weeks. I’d read piles of parenting books, some of them fairly compelling. But in the heat of the moment (and some moments got very hot), their abstract principles went out the window. Why couldn’t my son be easygoing like his sister?

At the outset, Dr. Dan teaches you how to get to know your child, his strengths and weaknesses.

Kids do well if they can, he’ll say.

Parents know their own children best.

And: What’s right and wrong in parenting is often about what’s right and wrong for each individual child. Which is to say, every kid is different.

“Before I met Dr. Dan, I was always asking myself, ‘What am I doing wrong? Did I eat weird shit when I was pregnant? What is wrong with me as a parent? Why can’t I just drop my kid off at preschool like everyone else?’ ” says Chelsea, the mother whose eldest has ADHD. “Dr. Dan helped me realize that some children come out a certain way and that is what leads them to a certain behavior.”

This is why that brilliant parenting trick that works for your friend every time her kid throws a fit may not work for you, and why you shouldn’t feel like a failure if it doesn’t.

It’s also why the one-size-fits-all approaches of your typical parenting book don’t always resonate.

Dr. Dan has read all the books. In fact, his curriculum is a sort of greatest-hits compendium of major works of child-development theory spanning a half century, a distillation of their wisdom into bite-size chunks.

“Kids do well if they can” comes from Ross Greene’s 1998 book, The Explosive Child, a Shapiro favorite. From B.F. Skinner, a father of applied behavior analysis, he took insights on motivating people to do things they don’t want to do. He based his group approach on Russell Barkley’s Defiant Children manual, and he drew on the work of renowned child psychiatrists Stella Chess and Alexander Thomas as well as pediatrician William B. Carey, who posited that all children are born with their own behavioral style. He borrowed, too, from Martin Seligman’s 1990 book, Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life, to encourage parents to avoid pessimistic generalizations about their offspring (my own personal specialty).

Basically, once you know what makes your kid tick, you can apply Dr. Dan’s wide-ranging lessons. The one that parent after parent told me was among the most powerful was the so-called time-in. It’s just what it sounds like, the opposite of a time-out.

“Too often parents spend much of their time on undesirable behaviors,” Dr. Dan says, “and some children get conditioned to dread the sound of their own name. They think, ‘When I hear my name, I’m going to be told I did something wrong or be asked to do something I don’t want to do.’ ” Instead, kids should learn to have positive expectations with their name: “I’m not going to be criticized; I’m just going to have my parent’s presence.”

To do this, he says, parents should make an effort to spend time every day—even just five or ten minutes—one on one with their child, doing whatever she wants, without asking questions or offering corrections, and definitely without checking the phone. “Just enjoying each other,” Shapiro says. “So when it comes time to question and command and assign, it’s more balanced.”

During my class, Dr. Dan called a parent to come up and role-play how a time-in should go. Shapiro (as parent) started playing trains with the audience member (as kid). When the “kid” crashed his toy into a wall, Dr. Dan made a crash sound and feigned total engagement. He asked no questions, offered no criticisms or life lessons—he just played merrily, nonjudgmentally along.

Putting the trick into practice can take, well, practice. As Nadine, the mother of the necklace-yanker, says, “I was with my daughter yesterday at a coffee shop and she drew a picture and I was like, okay, back to my magazine. But then I thought about Dr. Shapiro and I asked her, ‘What’s in that picture?’ And it’s very hard for me.

“But it changes the dynamic so much because I’m really having a conversation with her and she’s really excited to tell me about it. I was just really positive, and I kept saying, ‘Wow, that’s really interesting.’ ”

The other big technique Dr. Dan emphasizes is empathy. It might not feel intuitive (so much doesn’t!), but when a kid is screaming, say, that he doesn’t want to eat dinner, the parent, rather than excoriating the child, should try to “roll with the resistance.” So instead of repeating, “Get to the table now!,” you say, “Oh, I guess you don’t want to eat dinner? Sometimes people tell me to do stuff that I don’t want to do, too.”

This gentler approach is far likelier to result in the kid actually eating his dinner. Shapiro borrows the metaphor of a car skidding on an icy road; to avoid an accident, you don’t turn the steering wheel away from the ice but toward it. “Once the tires are able to rotate with the momentum of the car,” he says, “then and only then can you regain traction.”

The tool has worked well for Nisreen, an economist who sees Dr. Dan for her child and attends his classes. “I have to remember that I am talking to a little person,” she says. “Don’t shout from upstairs—get down on your knees and get on your child’s level. Don’t speak at the six-foot level—speak at the four-foot level. Just this simple thing changed my whole relationship with my son.”

In my household, the time-in made a dramatic difference on my first try. I’d never realized how little time I spent one on one with my son, but as soon as I really committed to activities on his terms, he responded immediately. Was it really so simple as spending 15 minutes a day building a Lincoln Logs cabin with him? In a bizarre and after-the-fact-very-obvious-seeming way, it sort of was.

Why had this never occurred to me before? Why didn’t I play more with my kid instead of always trying to correct him? And why couldn’t I give my clumsy southpaw more time to buckle his seat belt?

As Christina told me: “Letting the child lead, doing something without an agenda—on the one hand it’s like, duh, and on the other it’s the most difficult thing in the world. . . . It’s pretty sad that someone has to teach us this!”

Perhaps. But then again, obvious isn’t always intuitive, especially when it comes to kids. Most of us are too busy keeping them alive from one day to the next to pause and ponder their unique humanity.

With hard work, I’m getting over time-outs, my old addiction. Dr. Dan suggests limiting them to occasions when kids are dangerous—which, even at his frequent worst, my son rarely is. Instead, Shapiro recommends artfully ignoring the behavior until the moment passes. To my considerable astonishment, this trick works, too: My son runs out of steam far more quickly when I simply walk away than when I drag him upstairs and shut him in his room for the prescribed five minutes. Because I’ve become so skillful at ignoring the tantrums, they’re coming less and less often.

I had the opportunity to practice my newfound restraint on a visit to the White House this past spring for the Obamas’ Passover Seder. My husband used to work for the administration, and (with future rehearsal-dinner slide shows in mind) we have occasionally brought our kids in for a brief photo op before the dinner, always without incident. But this year, my two-year-old decided—no, demanded—to change dresses the second before our hosts walked into the room. When I told her no, she threw herself on the floor—right at the President’s feet. Instead of blanching or shrieking, I simply looked down at her and laughed. Sure, her timing wasn’t ideal, but she was two—what else could I do but wait for the storm to pass?

The President, calm as ever, was unfazed by the explosion. But when a picture of the meltdown later went viral, parents worldwide excoriated me as a parent (all too typical of 21st-century liberals, apparently). Still, I felt proud of the restraint that does not at all come naturally to me. (The tantrum subsided within seconds, by the way, as precipitately as it had begun.)

I sent the shot to Dr. Shapiro for proof of how far I’d come in the six months since sitting in his first class. He wrote back, “VERY FUNNY PICTURE!,” and I felt as if I’d earned an A.

Washington writer Laura Moser has contributed to the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times.

This article appears in our August 2015 issue of Washingtonian.