When you think of Civil War photography, you might think of the man known as the father of the genre, Mathew Brady, and not his one-time assistant, Alexander Gardner. Many of Gardner’s photographs are iconic, especially his portraits of Abraham Lincoln and his battlefield images of Antietam and Gettysburg. But his earlier works were actually attributed to Brady, who often took credit for the work produced by photographers in his studio.

With an aesthetic that’s uncannily modern, “Dark Fields of the Republic,” an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, looks at the rich body of Gardner’s work and gives him credit for creating an important visual vocabulary of the years surrounding the Civil War. With studio portraits, battlefield scenes, and western expanses spanning from 1859 to 1872, the exhibition masterfully transports its viewers back to a turbulent and critical period in American history.

Brady hired the Scots-born Gardner in 1856 and, a couple years later, put him in charge of a new studio in Washington, where Gardner spent most of his time making portraits of society’s movers and shakers. Abraham Lincoln was one of his clients.

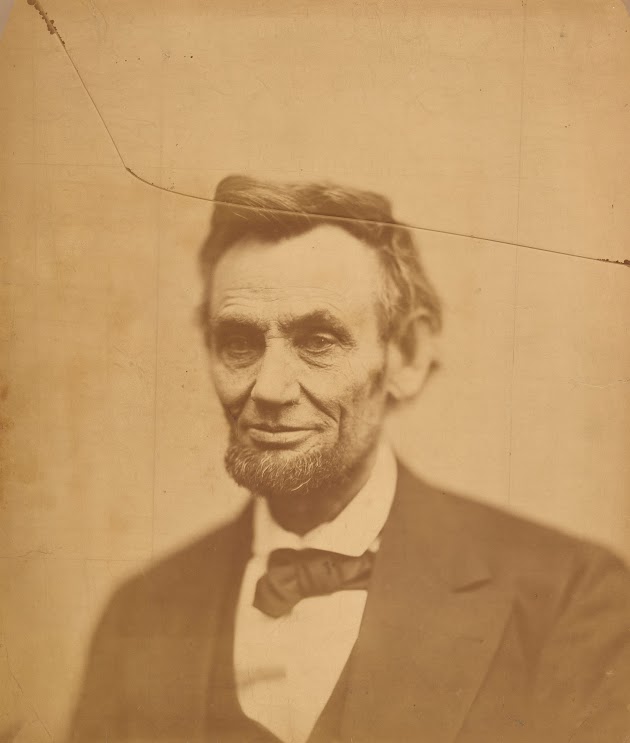

Gardner quickly became Lincoln’s go-to photographer. The commander-in-chief realized early on the power of photographs in shaping his public persona and often posed for Gardner. Among several Lincoln images on display is the rarely exhibited “cracked plate” portrait taken weeks before his death. The photograph earned its name when the glass negative was heated and cracked; Gardner was able to pull just a single print from it. According to exhibition curator and Portrait Gallery senior historian David C. Ward, the portrait is an “accidental masterpiece.”

“The way that the portrait is composed, Lincoln is present to us but almost seems to be disappearing. When Lincoln dies, he becomes this martyred, saint-like figure,” Ward says. “We put all the weight of our expectations and failed hopes on the body of the dead president. We wouldn’t read the picture the same way if he hadn’t been assassinated.”

Studio portraiture sustained many photographers in that period, and the exhibition displays wonderful examples of that aspect of Gardner’s work. The exhibition also shows how Gardner ventured outdoors to document historically significant places and events, such as Washington’s Tomb at Mt. Vernon and Lincoln’s Inauguration in 1861.

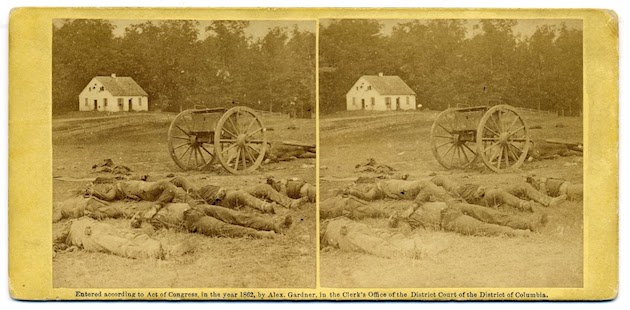

When war broke out, Brady sent his staff photographers to follow Union troops. Gardner arrived at Antietam just after the bloodiest one-day battle in American history had claimed more than 25,000 casualties. His images of the battlefield strewn with dead bodies captured the savagery of modern warfare. Their sobering reality both fascinated and shocked the American public; the images sold well and established Gardner’s reputation.

In late 1862, Gardner left Brady and established his own studio in Washington. He continued to document military campaigns and battles. Gardner was the first professional photographer at Gettysburg and again profited from taking images similar to Antietam. The photographs deeply influenced Lincoln, who viewed them in Gardner’s studio not long before giving the Gettysburg Address. By war’s end, Gardner was the quasi-official photographer in Washington.

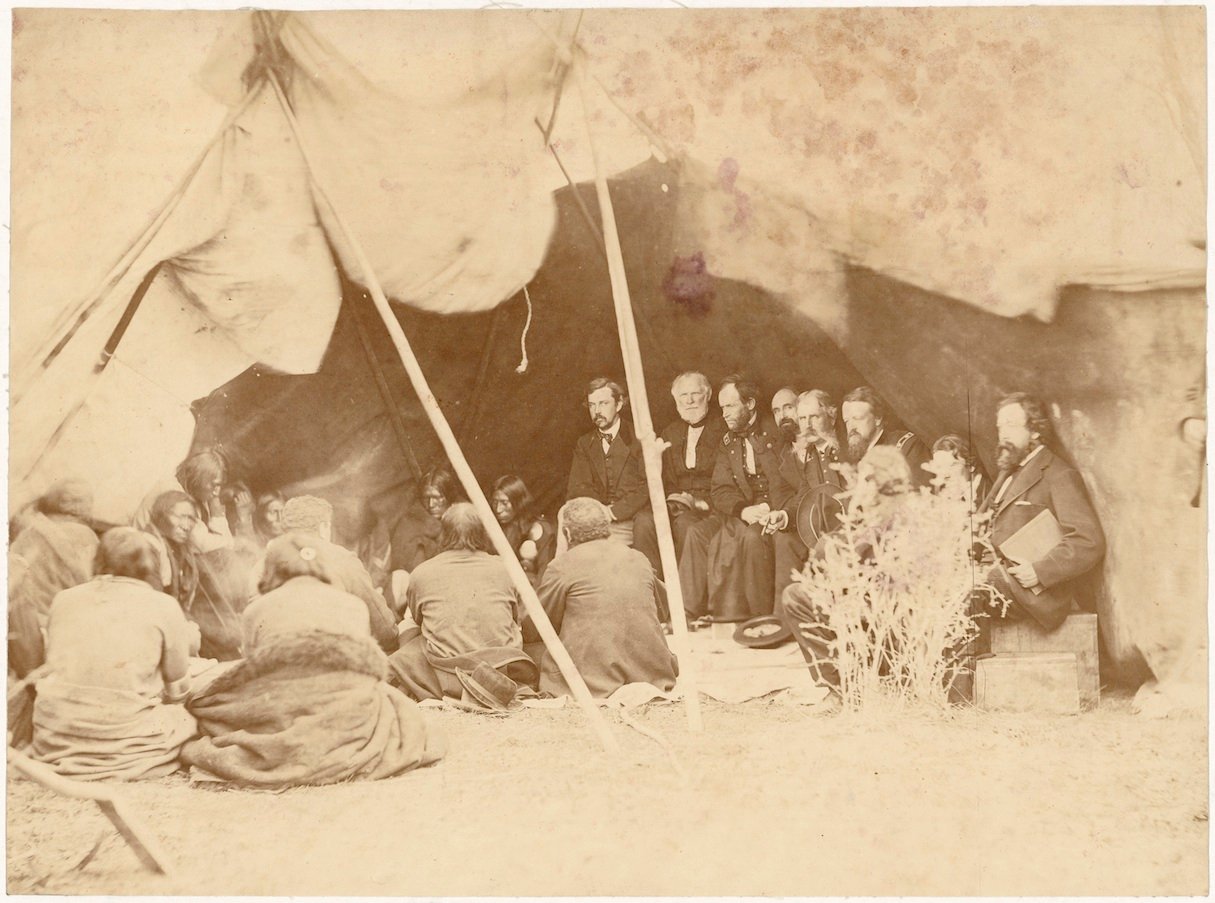

Before leaving the photography business in 1872, he headed west on commissions to document the proposed route of the transcontinental railroad as well as treaty negotiations with Northern Plains Indians. He returned with images of Native American encampments, Army forts, frontier settlements, and expansive landscapes, which provided the American public with a deeper understanding of their evolving nation and the west.

“Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872” at the National Portrait Gallery runs through March 13, 2016.