It’s hard to imagine how our peerlessly inventive country would ever manage without our imaginary Presidents: The West Wing’s Jed Bartlet, 24’s Obama-anticipating David Palmer, and that ass-kicking Prez played by Harrison Ford in Air Force One. Free World–ing it up in TV shows, graphic novels, action movies, and, most recently, a fun batch of video games, our virtual Presidents far outnumber history’s 43 incumbents—Wikipedia’s list runs to 600 names, so many that they’re broken up alphabetically.

With the candidates for the White House currently dominating cable news, making reality look less like fact and more like an option, our fake Presidents seem especially necessary. They appear to sprout up in exact proportion to how alienated all those strangers west of Leesburg are by the real McCoys. Chances are the fakes have inspired more public servants to relocate to DC than any of the stony-faced jokers on Mount Rushmore have.

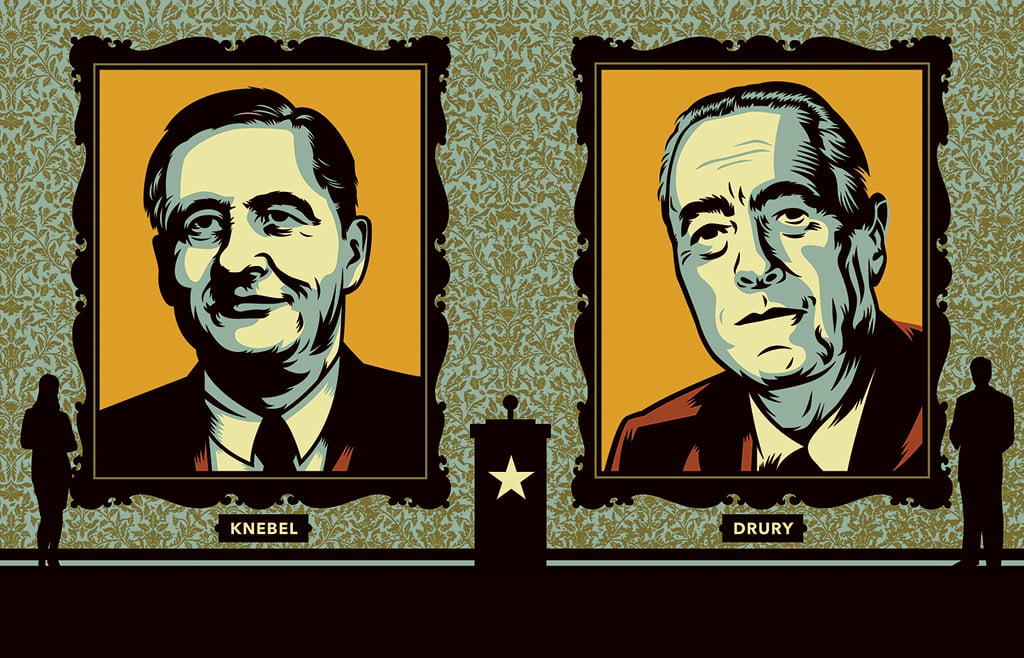

So let us now praise Allen Drury and Fletcher Knebel, the all-but-forgotten founding fathers of this fantasy industry. Advise and Consent, Drury’s overwrought (he’d get worse) but riveting 1959 novel, depicted a Senate thrown into disarray by the President’s nomination of a suspected former pinko to his Cabinet. Three years later, Knebel, writing with Charles W. Bailey II, added pop thrills and a bleeding-heart agenda to pump out Seven Days in May, in which Pentagon brass hats plot a coup against their peacenik commander in chief.

Pop culture has passed both men by, but Wikipedia’s list would be much shorter had they not unburdened themselves of a trove of Washington lore. Understanding their books, if not actually reading them, is still crucial for anyone presuming to know how the capital works.

Advise and Consent and Seven Days in May both appeared early in the Cold War—a period, strange as it sounds today, when Capitol Hill seemed a serious place. It was also a time when the cultural distinction between high and low, serious and frivolous, began to fray permanently. The divide persisted enough, however, that both novels felt like audacious breaks with tradition.

A century before in England, the imperturbable Anthony Trollope had parked Plantagenet Palliser at 10 Downing Street in The Prime Minister without anyone objecting that Benjamin Disraeli had the job. In the US, the occasional Of Thee I Sing spoof aside, a very American combination of piety and indifference vetoed the executive mansion as a setting for made-up high jinks. Even Henry Adams, in his 1880 political soap, Democracy, took care to keep “Old Granite” or “Old Granny”—the otherwise anonymous President (as in Definitely Not Ulysses S. Grant) who putters around in the margins of the novel—mostly offstage and mute.

Democracy’s status as the classic Washington novel can be attributed partly to the fact that, between Teddy Roosevelt and Ike, no one could be bothered to try to write one. Only the cognoscenti cared about the genre anyway, and that suited most Washingtonians just fine. District lifers took pride in the unintelligibility of the political class’s arcane ways.

Drury’s very knowledgeable melodrama reversed the trend. Swollen to 616 ant-dance pages in its first edition by Drury’s mile-wide fustian streak, Advise and Consent was chock-a-block with zoological nuggets the author had stored up in more than 15 years of covering Washington for the United Press and the New York Times. The country flipped for the novel, which spent almost two years on the Times bestseller list and copped the 1960 Pulitzer Prize. (True, only after the board decided Saul Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King was a little too froufrou.)

Washington, meanwhile, was captivated by its fun-house-mirror reflection. One of the more charming photographs of Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy together shows Nixon happily leafing through Drury’s novel as his chipper 1960 White House rival looks on, although Nixon was possibly just relieved to discover he wasn’t in the book. Disguised as womanizing senator Lafe Smith, JFK was.

Drury always got testy at the notion he’d simply written a roman à clef. But the fact is he had a gift for synthesizing recognizable contemporary individuals and the eternal Washington types they represented. His nameless President’s ruthlessly seductive guile was FDR to the teeth, more so once Franchot Tone, looking a lot cagier than in his 1930s male-ingenue days, played the part in Otto Preminger’s screen version—still the greatest of all Washington movies.

Drury’s story line, too, blended headlines still fresh in the public’s mind with political inside-baseball, to irresistible effect. The confrontation that gums up liberal darling Robert A. Leffingwell’s all-but-certain path to becoming Secretary of State was an inspired twist on Alger Hiss’s 1948 exposure as a commie, in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee, by the unlovable Whittaker Chambers. Even the suicide that prompts Advise and Consent’severything-but-the-kitchen-sink climax was modeled on the lonesome 1954 death of Wyoming senator Lester Hunt.

The book’s most ingenious reinvention was turning right-wing demagogue Joe McCarthy into a rabid left-wing fink named Fred Van Ackerman (slogan: “I had rather crawl on my knees to Moscow than die under an atom bomb”). Drury’s own politics would have gladdened Ronald Reagan’s heart. And did: The Gipper once named Drury as one of his favorite authors. While speaker, Newt Gingrich duly included Advise and Consent on a reading list for House freshmen. Drury’s onetime UPI crony Helen Thomas wondered “how he could stand” his fellow reporters’ company: “He was so conservative, and we were all so liberal.”

Yet the boldest element in Advise and Consent—remember, this was 1959—is that its most sympathetic and heroic figure is a closeted (well, duh) gay senator who achieves serenity at the moment he dies by embracing that identity. He’s also a man around Drury’s age who, like his creator, was a proud Stanford grad. If they had other points in common, Drury went to his grave without acknowledging them.

It was the plot’s homosexual affair that caused New York Times film reviewer Bosley Crowther to call the 1962 movie “deliberately scandalous” and “sensational.” Preminger upped the ante by casting Kennedy in-law Peter Lawford as the JFK stand-in. The director also hired a bunch of real-life Washington luminaries as extras, getting a big laugh at a DC preview when Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson was shown turning down a drink—a likelihood so remote as to make the plot’s most lurid mischief seem bland. Preminger even wanted Martin Luther King Jr. to make a cameo as a senator from Georgia, an offer King declined. In other words, if you’ve ever wondered precisely when Washington became a branch of the entertainment industry, here’s where it all began.

It’s unclear whether Knebel and Bailey were inspired to get cracking on Seven Days in May by Drury’s success, but if they were, they were hardly alone.

Eyeing the bestseller list and suddenly recalling that he knew a thing or two about politics, Gore Vidal dashed off his play about backstage convention doings, The Best Man, in three weeks and had it running on Broadway nine months after Advise and Consent’s publication. (The hit stage adaptation of A&C was playing three blocks away—those were the days.)

Seven Days in May has even less connection to capital-L Literature than Drury imagined he did, yet it was even more of a game-changer. It’s the prototype for every tick-tock Washington thriller about some menace to the republic that has to be thwarted pronto.

Knebel was known around town as a waggish fellow who’d spent years writing a folksy syndicated political column called Potomac Fever. (Sample joke: “A decline is when a friend borrows two-bits from you. A recession is when you remind him of it.”) He was also a soap-box liberal unnerved enough by Eisenhower’s Joint Chiefs chairman, the famously hard-nosed Admiral Arthur Radford—“He scared me to death,” said Knebel—to believe a military takeover was a genuine possibility once Kennedy came in.

In the novel, charismatic Air Force general James Mattoon Scott, in Radford’s post, is coolly orchestrating a very plausibly worked-out plot to overthrow idealistic President Jordan Lyman—has there ever been a fictional Oval Office occupant whose name was remotely convincing?—when one of his subordinates stumbles onto the plot.

It’s embarrassing how often I’ve reread the damn thing while Proust gathers dust. But we’ve all got our own ways of remembering things past, and Knebel and Bailey capture the nuts and bolts of my Washington: the peculiarities of Fort Myer’s layout, how a Marine colonel on the JCS staff can hobnob with White House aides while driving a beat-up car and living in a run-of-the-mill Arlington house, the Washington cocktail party where everyone’s a heavyweight and no one is particularly glamorous. If only the duo had had a gift for character, not just cookie-cutter collections of attributes, the book might have survived as more than a catch phrase. But they didn’t, and it was left to John Frankenheimer’s 1964 movie version to solve the problem by adding Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas’s outsize personalities.

After the screen version of Advise and Consent appeared, Drury grumbled that Preminger had muddied his anti-Communist message. Knebel could have no such complaint about Seven Days—not with half of Hollywood’s liberal leading lights in the cast or behind the camera, eager to warn us that the military-industrial complex might one day opt for simplicity. JFK was equally enthusiastic about getting Seven Days in May on the screen, especially after the Cuban Missile Crisis, when Air Force chief Curtis LeMay’s willingness to risk nuclear war had rattled Kennedy.

Decades before West Wing and Scandal fans could navigate the White House blindfolded, Seven Days’ filmmakers were given the run of the place to get every detail right—except, it turned out, the poignant sight of the nautical murals of St. Croix that Kennedy commissioned for the swimming pool: By the early ’70s, when the book and film are set, Nixon had converted the pool into the press briefing room and the murals were long gone.

So, of course, was JFK when Seven Days in May reached theaters in February 1964 (the same week the Beatles hit America—one of those time-capsule juxtapositions that evoke a lot despite meaning little). Even half a century later, Kennedy’s assassination goes a long way toward explaining our love of invented presidencies. No matter how nutso they can get, they just seem safer.

Knebel never again thought up a gimmick half as snappy as Seven Days in May. His later novels, written solo, are even more liberal politically—not that anyone was reading them for their ideology—but no more compelling. Night of Camp David comes closest by simply inverting the earlier book’s formula: It’s now the good guys who are out to remove a President they think has gone psycho before he does something loony at a summit meeting. Among the hero’s reasons for thinking President Hollenbach has gone insane is his scheme to wiretap every American’s phone. Bonkers, right?

Keeping up with the times, Knebel tackled his beloved JFK’s Peace Corps (The Zinzin Road) and black militancy at home (Trespass). In between came 1968’s Vanished, about a White House confidant who disappears without a trace. A decent thriller, it collapses only in its last pages when it becomes yet another variant on Knebel’s fantasy of a President nobly ending the arms race. By then, however, he had too much competition. Fellow syndicated columnist Drew Pearson (or his ghostwriter) published The Senator in ’68 and followed it with The President. Rod Serling, creator of TV’s The Twilight Zone and screenwriter of Seven Days in May, cooked up The President’s Plane Is Missing. After 1986’s Sabotage, Knebel more or less gave up. Suffering from lung cancer and a bad heart, he took his life in 1993.

The ’60s, meanwhile, had unhinged his right-wing doppelgänger. Drury swapped the astute firsthand observation that had fueled Advise and Consent for the gasbag delirium of its increasingly hysterical sequels. Venting his disgust with liberalism and, above all, the liberal media, his 1968 offering, Preserve and Protect, envisions a mob of rancid hippies, uppity black radicals, and uniformed neo-Nazis surrounding the Kennedy Center—the emergency locale chosen to pick a new candidate for President after the incumbent is killed—to impose their will on the stout-hearted patriots trying to hold the USA together.

“My God, do you see what those guys are doing to the flag?” one stout-heart asks. “They aren’t only urinating on it, they’re dropping their pants and—” (Probably not going skinny-dipping in the Potomac.) Drury wrote a number of other novels before his death in 1998, but the fall from Pulitzer winner to much-ridiculed zealot must have been hard.

Call me sentimental, but this was the bilge of my formative years. Today there’s no real reason to read either man unless you’re into literary archaeology. But considering what they spawned, a modest statue to Drury and Knebel somewhere in the District might not be amiss. (Bailey, too? By all means—Bailey, too.) Unless a hologram would be more suitable.

Tom Carson (@tomcarsonwriter) is a freelance culture critic and author, most recently, of “Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter,” a novel.

This article appears in our January 2016 issue of Washingtonian.