Three years ago, when Renwick Gallery curator Nicholas Bell presented the exhibition “40 Under 40: Craft Futures”—which pulled together a sampling of the new generation of American craft artists—Bell himself was only 32. Then this past September, as the Renwick was about to emerge from a two-year renovation, he was named curator-in-charge. Bell’s first exhibit in that capacity, “Wonder,” has seemed to rejuvenate the museum, filling its galleries with installations by nine contemporary artists whose efforts add up to a single gasp-worthy work.

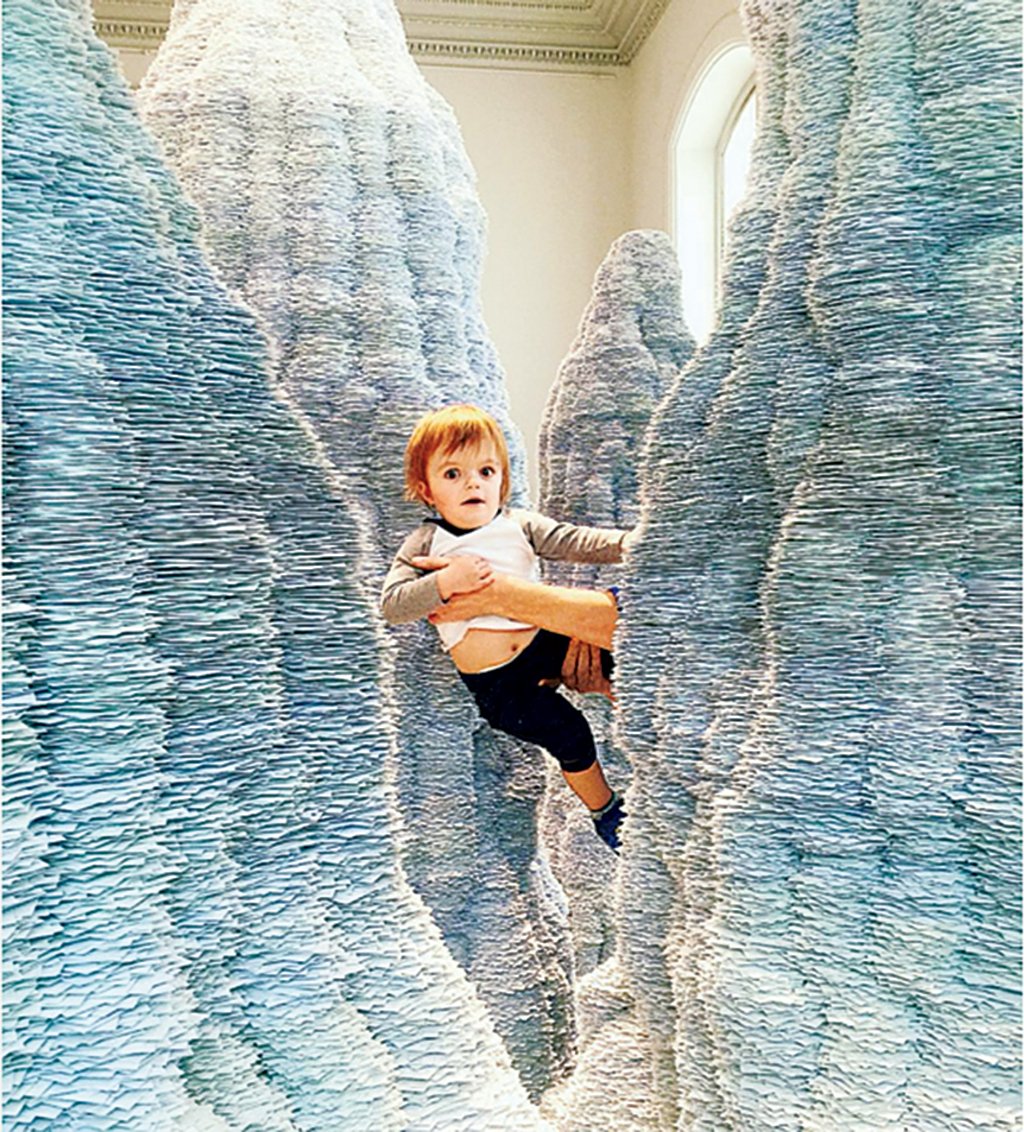

The show has also captured craft’s growing importance in American art and has made the Renwick, the Smithsonian’s branch for craft and decorative arts, its sudden center. In its first month, “Wonder” drew some 100,000 visitors—nearly as many as the Renwick used to see in a year—and quickly became one of the most Instagrammed spots in Washington.

Digital celebrity, however, was never the goal. A scholar of everyday objects (known as “material culture”), Bell wanted “Wonder” to “remind people why museums as physical places need to exist.” We sat down with him to discuss museum-going in the internet age and what to expect next from the Renwick.

Did you expect “Wonder” to become an Instagram phenomenon?

I had never been on Instagram. I didn’t have an account—nothing. So I really had no idea what a sensation this would turn into. But the artwork—the colors, the scale—lends itself to the medium. People are reacting to the art. They are lying on their backs, gazing up all day. People are doing yoga. We had a pop-up wedding.

People have discovered that we don’t turn the lights off on the installation until 11 pm and that if you stand in just the right spot on the sidewalk in front of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, you can watch Leo Villareal’s light installation in the stair hall glimmering. Crowds have started gathering out there at night. We’re so delighted. I’ve had curators from other museums asking how they can gin up a similar response.

What do you tell them?

The answer is quite simple: encourage people! We’re actively encouraging photography, which is a total change in mindset. When we first created the signage, it read “photography permitted,” but it felt so begrudging, like “I guess you can take a photo.” Once we changed the signs to “photography encouraged,” it changed the whole atmosphere of the rooms.

I saw it first on Instagram, but the intensity of the experience in person is unbelievable.

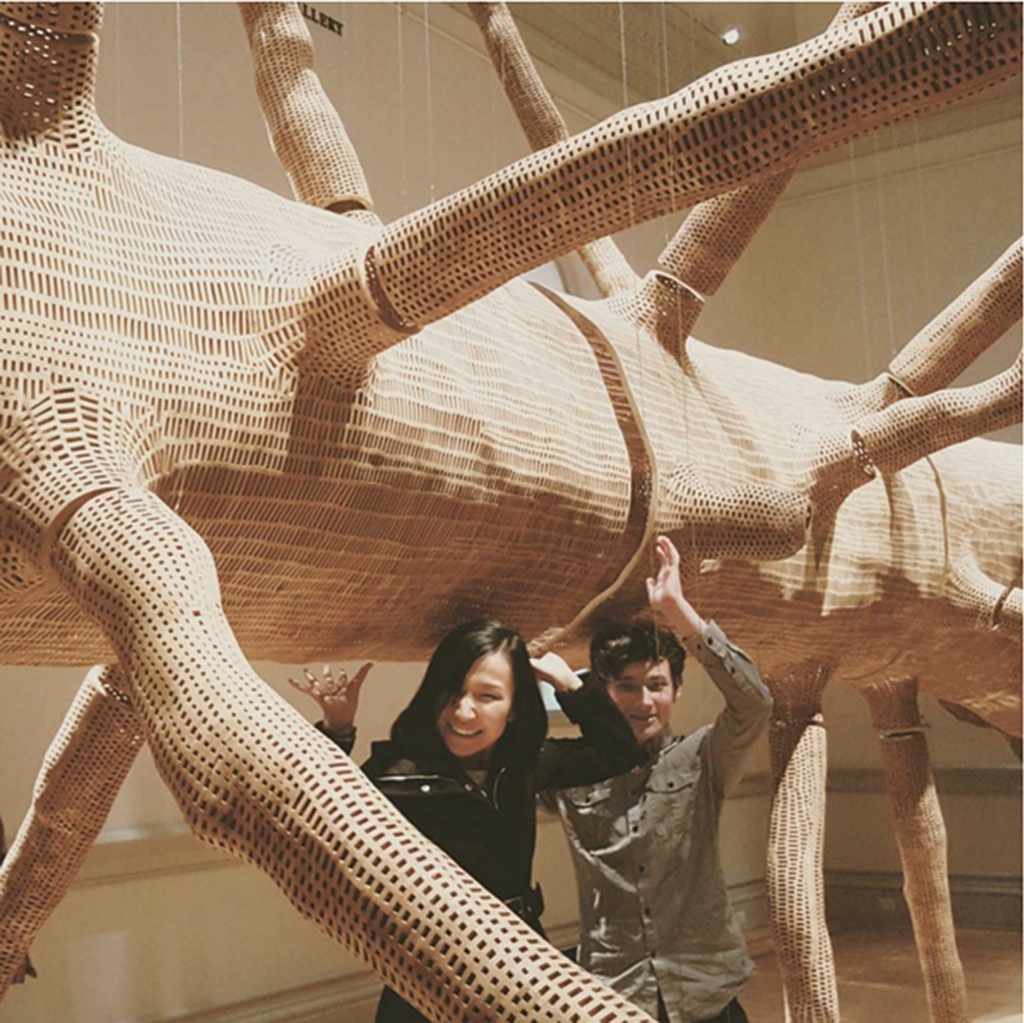

Oh, yes. Standing underneath Janet Echelman’s netting or gazing into John Grade’s hemlock tree is a physiological, immersive experience. We really focused on the materials to achieve that. We’ve hosted exhibits before that showed much smaller, quieter crafts. Baskets, for example [2013’s “A Measure of the Earth,” a collection of traditional American basketry].

I loved the baskets!

That one wasn’t a huge success, though, in number of visitors. With our relaunch, we wanted to be as literal as possible with the idea of being overwhelmed. We thought it was important that visitors not know what they’re looking at.

People self-select, you see. They make decisions about whether or not they’ll appreciate art before they’ve even encountered it. They drive their visit with their own biases. But this exhibition opens you up to the unknown. You are, in fact, in a state of wonder. Most beautifully, it reminds you why you should go to a museum at all. These huge, impressive pieces have a sense of presence.

Their exuberance does show how there are few limits on what we call craft, as opposed to art. Where do you see American craft headed?

Our ideas about what should be included in a definition of “American craft” have evolved dramatically in the past 15 years. Previously, at least in museums, the definition centered around highly trained individuals exploring techniques and aesthetics within a set range of media—glass, clay, metal, wood, and fiber. This is what’s known as the studio craft movement, which rose rapidly after World War II, through new programs created in the wake of the GI Bill. It’s been waning as those postwar generations get older. Since about 2000, a groundswell of interest in craft as an activity has helped change how we in institutions think of it.

Thanks to sites like Etsy and all the DIY bloggers.

Yes, the rise of DIY and Etsy, “craftivism,” guerrilla craft shows, and Maker Faires all illustrate the new attitude toward craft, based less on careful cultivation of particular manual skills and more on craft’s social potential. Our perspective has evolved from thinking of craft as a noun to a verb—from the thing skillfully made to the act, and enjoyment, of making. Museums are exhibiting a whole new range of creative work that is now more loosely defined. It’s helping us understand more clearly what it means to be a “maker” in the modern era.

Where do you draw the line between hobby and art?

It is a continuum without clear boundaries. At the Renwick, we focus on people who are intensely passionate about what they do and who involve themselves intimately in the act of making. So what distinguishes works at the museum from what you might call the hobby sphere is the right combination of skill, concept, aesthetics, and a quality often in evidence at the Renwick—obsession. As a museum devoted to the way things come into being in the modern world, this final quality raises some things above others. We show makers who are driven to achieve their goals, because that helps us as a society grasp the value of skilled making, of craft.

You’ve also created a very ecologically minded show: Maya Lin’s homage to the Chesapeake, Janet Echelman’s nod to the Japanese tsunami, Jennifer Angus’s concern over insect extinction.

You know, I’ll take the credit, but it truly wasn’t intentional. [Laughs.] The reason, I think, is that the artists are determined to look at what really matters in this world. They know how to present art that does that without hitting you over the head or preaching.

Let’s talk about changes to the building itself. What was the guiding principle, aesthetically speaking?

Of course there was only so much we could do, because we couldn’t change the floor plan. Ninety percent of the change is in the walls—updates to ventilation and heating, et cetera. So what people are responding to is the 10 percent they can see, and the most dramatic change there was the paint palette. We took it all back to a very clean, light paint, with just a touch of refinery in the gilding.

When the building opened [as part of the Smithsonian] in 1972, it was going for a faux-Victorian, 19th-century aesthetic. Dark wall colors, heavy drapes, very formal. We stripped that all back—sanded floors, opened ceilings, uncovered windows. We didn’t want to pretend anymore.

What about the red carpet that greets visitors?

That rug is so playful. It flows like blood down the main stairs and puddles at the bottom. You think you’re going to see a red carpet when you enter a museum, but that’s not what you picture. We just wanted something fun, so we turned to the French artist Odile Decq. That red is her signature color, and given the building’s French influence—it was modeled after the Louvre—it just made sense. She’s taking something that someone would ordinarily pay no attention to and making it a focal point.

Given its long fallow period, what need do you see the Renwick serving for Washington now?

The renovation of a museum of this caliber is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to remind people that you exist. We wanted to remind the city that this is a place to have a conversation about what it means to make things, and that the craft movement is not fading—if anything, it’s growing stronger.

How do you plan to keep the momentum going? Do you have more innovation up your sleeve?

Nora Atkinson, our curator, has completely reimagined our permanent collection in a way that breaks free of conventional organization. Instead of grouping like with like—“Here’s all the ceramic work, here’s all the craft from the late 19th century”—she’s used the internet’s hyperlinks as inspiration. Walking through the permanent collection, you’ll leap from object to object. There will be a narrative connection, but it won’t be what you’re used to.

Design and style editor Hillary Kelly can be reached at hkelly@washingtonian.com.

This article appears in the February 2016 issue of Washingtonian Magazine.