Georgetown was once a predominantly African American neighborhood, and photographs from that time are featured in Georgetown University Press’ Black Georgetown Remembered, first published in 1991 and reissued this past February.

In its early years, Georgetown was an independent tobacco and shipping port that received large shipments of Maryland’s tobacco crop. In 1800, Georgetown and some areas outside of Georgetown’s current boundaries had a population of 5,120, including 1,449 slaves and 277 free blacks, according to the book. Slave trading was banned in the federal district in the mid-nineteenth century, but the lucrative practice continued in Georgetown. Slaves were auctioned off just like books, kitchen furniture, and bedding, according to an advertisement in an 1834 issue of the National Intelligencer.

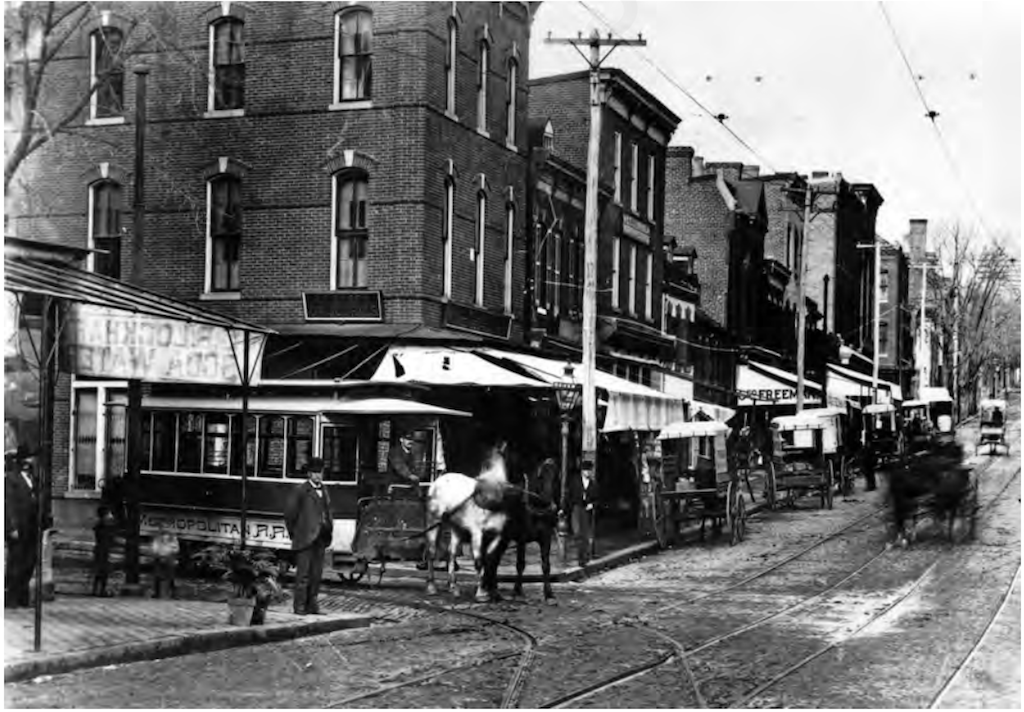

From 1900 to 1910, federal employees began to settle in Georgetown. Housing became more competitive and expensive; the average price of a house on Prospect Avenue averaged $2,500. Though this inflation drove out many lower earning African Americans who had been living in the area, black small businessmen and professionals were able to stay.

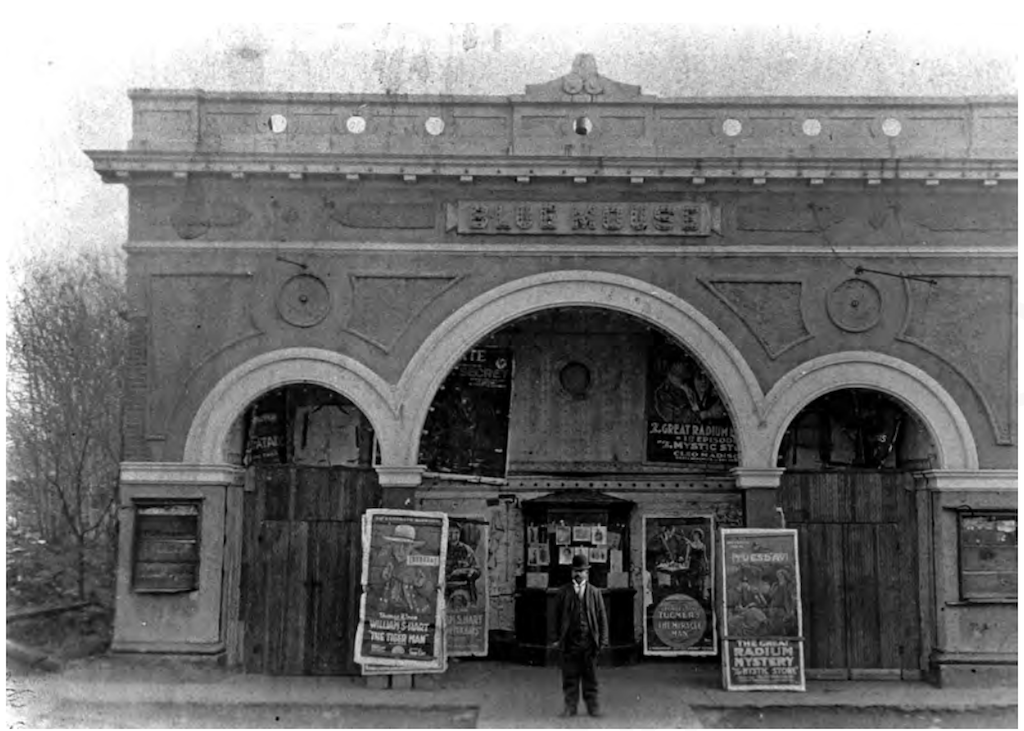

This black theatre was a popular center for community entertainment, regularly playing movies and vaudeville. The cost: about a nickel or a dime, according to one man’s recollection in the book.

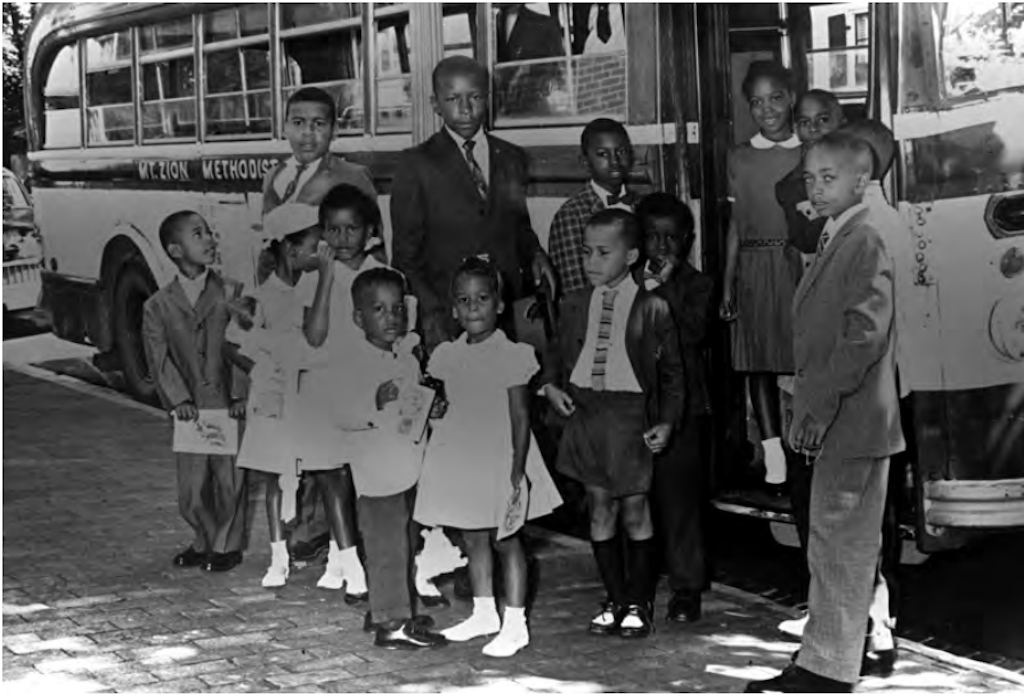

Black Georgetowners created the Rock Creek Citizens Association in 1916 to improve the safety in their neighborhood, deal with issues of police conduct and improve playgrounds, street lights, alleys and street cleanings. The organization also once boycotted Georgetown’s bicentennial celebration in 1951 because they said it it ignored black citizens during planning stages. Other social groups, including black fraternal clubs and men’s and women’s church groups, played a large role in Georgetown service projects.

Before DC’s recreation department placed “For Coloreds Only” signs on Rose Park in 1945, it was an unofficially integrated playground, often luring in “distinguished people who played tennis there, including Gene Kelly,” according to the book. The Rock Creek Citizens Association destroyed the signs and rounded up a petition, resulting in one of the few integrated playgrounds in DC.

Black leaders were often found serving in churches and advocating against developers trying to rezone two black cemeteries, known today as Mount Zion Cemetery. Developers wanted to dig up the bodies and build expensive townhouses in its place. The cemeteries included the remains of notable African Americans (including one of the builders of Mount Zion Church).

Today only a handful of native black Georgetowners remain. Monica Roache is one them–her family has lived in Georgetown for five generations, and they’re featured in the documentary that accompanies the book.