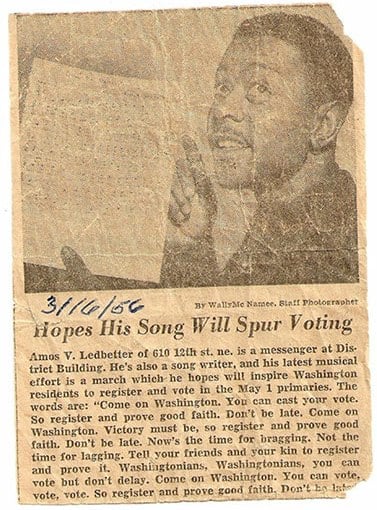

In 1956, residents of the District of Columbia were able to vote in a presidential primary for the first time in 82 years. They couldn’t vote in a presidential election–that change wouldn’t come until the 1961 ratification of the 23rd Amendment. Still, activists and community leaders began to urge citizens to take ownership of their say in the policies of the nation. One of them was named Amos V. Ledbetter.

Ledbetter was a longtime messenger in the Wilson Building and later a federal probation officer for 13 years. His daughter, Aquila Ledbetter, remembers him talking politics constantly around their house on 12th Street, Northeast. He closely followed happenings in Congress. He read extensively on politics–and forced each of his six children to do so as well. He was also a talented musician.

Ledbetter was a longtime messenger in the Wilson Building and later a federal probation officer for 13 years. His daughter, Aquila Ledbetter, remembers him talking politics constantly around their house on 12th Street, Northeast. He closely followed happenings in Congress. He read extensively on politics–and forced each of his six children to do so as well. He was also a talented musician.

In 1956, Ledbetter’s passion for the Democratic process led him to compose a song encouraging Washingtonians to own their newfound right. “Come on Washington. You can cast your vote,” Ledbetter wrote, extolling those around him to participate in the primaries, scheduled for May 1, 1956. “You can vote, vote, vote. So register and prove good faith.”

“He always urged us to be leaders and not followers,” Aquila Ledbetter explains. Though her father passed away in 2001, she continues his–and her family’s–tradition of activism. Since 2000 she has worked as an election worker, and on Tuesday she will oversee Ward 2’s primary vote as a precinct captain for the DC Board of Elections for the second year in a row. Her godmother Charleen Curseen was also a precinct captain, and her godmother’s grandmother, Gertrude Galla, was one of the first African-American precinct captains, working in the Trinidad area.

Aquila Ledbetter is proud of her fther’s work and his deep commitment to voting rights as well as his commitment to music (she recently reacquainted herself with the alto horn). “It was about having the freedom to choose who you want to lead, trusting that a step in the right direction for residents would lead to rights for all. This was two years after Brown v. Board of Education,” she explains. “I’m sure Dad was thinking of the greater struggles of the era.”

Aquila Ledbetter holds up a framed image of the original 1956 article, printed in the Washington Post. Her brother, Vernon A. Ledbetter, begins humming in a low voice. His hands are wrapped around his trumpet for the moment, his fingers running through the notes even as he resists the urge to play. They begin to harmonize. “Victory must be, so register and prove good faith. Don’t be late. Now’s the time for bragging. Not the time for lagging.” They sing the cheerful melody a capella and from memory.

“He was always charismatic about the underdogs. The voiceless. The helpless. I find myself trying to do the same thing, always standing in the middle,” Aquila Ledbetter says after they finish. She adds that for herself and the other election workers, many of whom are repeat volunteers, the empowerment of voting is the bottom line. They aren’t doing this for a particular candidate.

I ask Aquila Ledbetter what her father would say if he were here today, witnessing this election year. We’ve been speaking for over an hour but I’ve not heard her mention a party affiliation or candidate.

She smiles. “He would try to encourage the voters to get out there and vote,” she says simply. “That was what he really cared about.”