A relocation to Philly or LA will inspire friends to point out the burgeoning art scene or influx of new restaurants. Move to DC and you’ll get an earful about brown-nosed Hill acolytes and Stepford staffers donning Ann Taylor Loft.

It’s easy to hate on a capital whose reputation so far precedes it that the city can rarely speak for itself. After all, griping about DC is practically a national pastime. Everything from its shitty Metro service to the staid vibe inspires more bashing from discontents, and outsiders, than most other cities.

Jennifer Close’s new novel The Hopefuls uses the discomfort of DC transplants as its backbone. But as it turns out, an entire novel’s worth of sulking over the city’s lesser charms is just as grating as someone’s 5-minute rant on the topic. It turns what could have been an insightful look into the power dynamics of marriage, the elusive nature of adult friendship, or the rot of jealousy, into 300 pages of unadulterated whining. And it takes a tired cliché of DC life and relies on it so urgently that it drowns out any real understanding of how the loneliness of a new city pecks away at us even in adulthood.

The Hopefuls is the story of Matt, an Obama campaign-staffer turned lowly grub at the White House counsel’s office, and his wife Beth, a journalist in transition. After Obama’s 2008 victory brings the couple from New York to DC, Matt hauls off to work each day, aloof to his wife’s unhappiness in “a city that was crammed full of jealousy” and driven by a low-simmering ambition to move up in the White House ranks. Beth despises DC and everything about it—the weather, the people, and especially the strange tics inherited by those standing within arm’s reach of power. And at first, Close’s DC knowledge will draw a chuckle and nod of recognition (The Soviet Safeway, Snowpocalypse panic, etc).

At a birthday party for another White House employee, Beth latches onto Ash, the bubbly Texan married to Jimmy, a staffer to whom Matt holds an ever-burning candle of devotion. The four quickly become a unit, sharing all their “secrets,” and a cleaning lady. Beth, the protagonist, feels simultaneously confused by Ash’s chipper affect, her Christianity, her homemade thank you notes, but also awash in devotion to the one woman who chooses to befriend her. Ash soon becomes one of Beth’s only outlets and a yardstick against which she measures her own marriage, prospects, and lifestyle.

Matt is a walking incarnation of Gore Vidal’s oft-quoted line, “Every time a friend succeeds, a little part of me dies.” After only 70 pages it becomes clear that Jimmy’s growing credentials may provide Matt with death by a thousand resumé paper cuts. Jimmy golfs with President Obama, preps him for a debate, and jets off to Hawai’i for Christmas break with the First Family. When he announces he’s leaving the White House for a plumb job at Facebook, Matt grips the table and sets his jaw for the entire meal. This imbalanced rivalry of the two couples holds most of the novel’s tension, although it eventually sags under the weight of its own misery.

A former editorial assistant at Vanity Fair, Beth ends up at a website called DCLOVE, dedicated to “showcasing the unique personality of our nation’s capital.” Needless to say, Beth does not feel inclined to showcase any bit of the capital’s personality, especially for “the Us Weekly of Washington DC.” But with her propensity for self-induced suffering, she heads to DCLOVE—with nary a coffee or meeting at another outlet to drop her name in the ring—to cover the hottest bachelors on the Hill and snowball fights in Dupont Circle.

Instead of settling in and slowly acclimating, Beth’s resistance to DC grows stronger, and Matt’s inability to climb the government ladder with any great speed wears at his ambition. Jealousy over Ash and Jimmy’s very existence squeezes itself into every encounter—Ash becomes pregnant and Beth can’t bring herself to dredge up any joy over it, declaring “sometimes it’s just really hard to be happy for other people.” Ash finds a part-time job selling Stella and Dot jewelry and Beth thinks of it as a “pyramid scheme.” Beth even whines that Ash and Jimmy make better chili. And on it goes, with Beth seething, whining, griping, and sulking her way forward. She doesn’t explore or try to understand her new home. She locks in on misery and pilots a course forward.

As Tolstoy’s old adage proves, unhappiness is the bedrock of much of great literature. Without discontent we wouldn’t have his Anna Karenina, or Jane Eyre, or Lily Bart, or Clarissa Dalloway, or Isabel Archer—miserable, fascinating women. A joyful protagonist doesn’t hold much interest. But those women, along with thousands of other literary mopes, are impressive feats because they explore and study their pain, seeking to alleviate it or even to compound it. Their thoughts spin barbed circles around their fates. They wrestle with the choices that will define their psyches. They grow. Beth does not.

Beth needn’t triumph over her misery to maintain our interest (Anna Karenina and Lily Bart are certainly a testimony to that). If we’ve learned nothing else over the past few years, it’s that the “unlikable” women of literature are often the most fascinating. But those unlikable women are also dynamic, forceful, and able to indict themselves for their missteps. In Anna, and Lily, and the others, we have women implicit in their own undoing. With Beth, we have petulance gone wild.

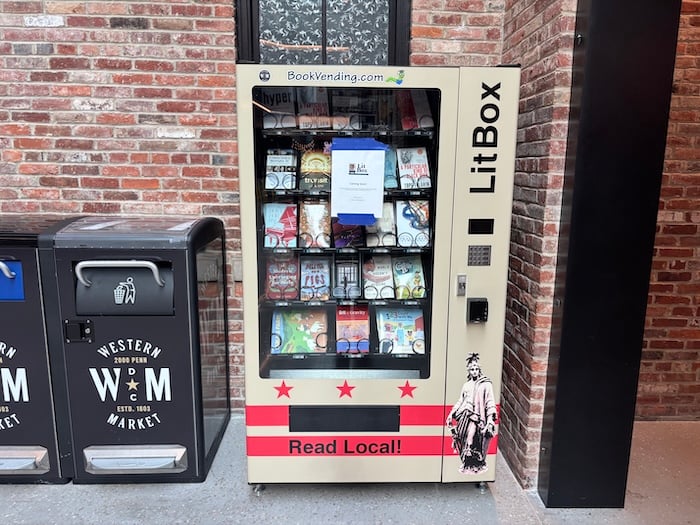

Close ably squeezes in winks and nudges to DC locals: Saint-Ex! 14th Street gentrification! Inauguration balls! The Panda Cam! Old Ebbitt! Verisimilitude in a novel of this kind is a necessity, and Close knows the hangouts and wolf whistles that will get locals nodding their heads. And there is certainly some joy to be found in tracing a character’s movements near your own, knowing that the barstools you’ve haunted have made their way onto the printed page.

But with Beth’s viewpoint as our only access into the novel, the spirit of the city lacks nuance and variety. When she attends a party and each person at the dinner table announces their security clearance (only Beth must shamefully announce she does not have one), it becomes clear that Close’s take on DC isn’t just one particular angle—it’s a gross exaggeration of a stereotype that’s been tossed around for decades. While DC is ripe for a send-up or a real look at the undergirding of such a cliché—and damn would I gobble up a book that thoughtfully skewered this town in all the ways it deserves—this just isn’t a novel that does either.

There is plenty to hate about DC (looking at you, Metro). And there’s nothing worse than a finger-wag about how someone else gets your city “wrong.” But the problem here isn’t that Close gets the city wrong, per say, it’s that her character never stops to wonder whether she’s getting it all right.

The Hopefuls

Jennifer Close

Alfred A. Knopf, 303 pp., $26.95