How Did a Wild Park End Up in the Middle of DC?

Picture this: You’re strolling along Rock Creek, soothed by the trill of the bubbling stream. Suddenly, you come upon a conservatory, a fence…and the Secret Service. It’s the White House, in the middle of the park.

Of course, none of that is real. But it could have been. Envious of New York’s new Central Park, Washington began lobbying for a city park in the 1860s, according to Scott Einberger’s A History of Rock Creek Park. At the time, downtown DC was a hot mess. Sewage flowed down the Mall, and little Willie Lincoln had just died of typhoid fever, likely from dirty water. Congress wanted to move the President’s home and find land befitting a public park. The job fell to Army engineer Nathaniel Michler. Luckily, he ignored half of his directive. What he called a “wild and romantic tract” was the ideal spot not for a white-columned estate but for a natural playground. In 1867, Michler pushed Congress to buy land around the valley before it became more valuable. Nothing happened for two decades. Finally, as the city’s edges crept closer to the forest, philanthropist Charles Glover helped get a park bill passed in 1890.

It’s thanks to Michler that the White House doesn’t overwhelm Rock Creek Park today, but there’s reason to celebrate that his plan wasn’t embraced fully. He had proposed developing the land with botanical gardens and exotic plants, even lakes. His manicured park, had it come to fruition, would have been very different from the wild retreat we know today.

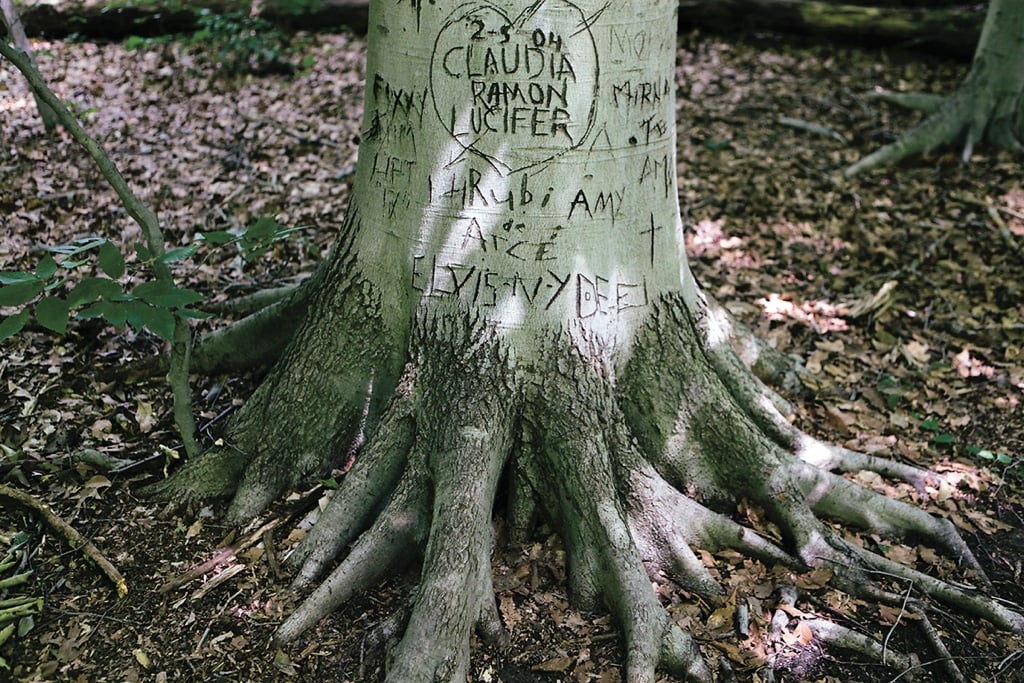

What’s Up With All the Carved Trees?

Initials, hearts, profanities—miscreants have long marked up the park’s American beech, a forgiving thin-barked specimen that unfortunately doesn’t heal well. While illegal, it’s a tradition that goes back to the 1930s and is arguably way more artful than the more contemporary method of leaving your mark: spray paint. “I can’t tell you the last time I saw a fresh carving,” says Michael Papa, NPS’s “tree guy” at Rock Creek, “but you go anywhere on the trail and all you see is paint.”

Why Is There a Highway Through This Great Natural Park?

Two words: Sunday drives.

In the early 1900s, Ford Model Ts were filling the driveways of middle-class homes, and parkways were created so families could spend their day off moseying along a nice country road.

A century later, Beach Drive and Rock Creek Parkway are no rural byway. But the twisty-turny strip of asphalt has its advantages—for some of us, anyway. Set off from the city’s grid, the road confounds newcomers and out-of-towners, who are left navigating red lights and intersections.

Summer tourists may stuff the Metro and hog every park-in space on the Mall, but learn the Parkway’s navigational quirks and you’ll have at least one piece of DC’s transportation system to yourself. It may look like a high-way that mars a natural redoubt, but it’s really a membership card in the Washingtonian tribe.

What’s That Smell?

Probably not the creek itself, according to NPS ranger Bill Yeaman. Although Rock Creek has plenty of time to accumulate pollutants on its 33-mile flow from a spring in Laytonsville, that summer stench you’re getting a nasty whiff of isn’t water-based. Instead, it’s gas venting from nearby manholes that gets caught in the park’s valley.

This article appears in our August 2016 issue.