A major DC institution is being invaded by Klingon speakers and cosplayers in Vulcan ears. As NASA begins its latest real-life mission to scoop up asteroid dust, sci-fi fans are celebrating their own extraterrestrial milestone at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum this week: the 50th anniversary of Star Trek’s 1966 television premiere.

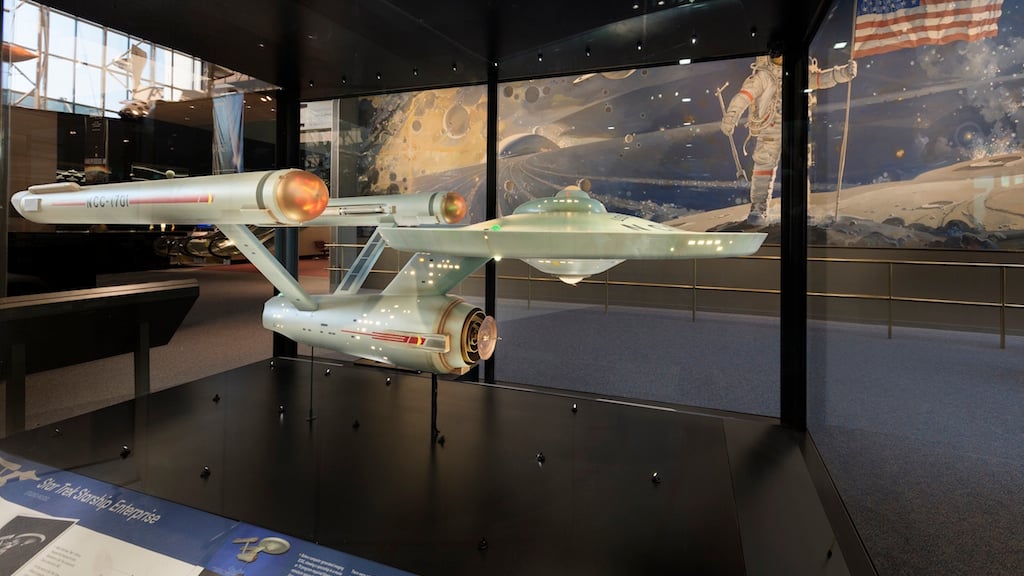

As the museum’s curator of social and cultural dimensions of spaceflight—in other words, the pop-culture curator—Margaret Weitekamp headed the effort to restore the original 11-foot model of the Starship Enterprise used in Star Trek shoots, now on permanent display in Air & Space’s newly renovated Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall, alongside John Glenn’s Friendship 7 capsule and the X-1 aircraft Chuck Yeager flew to smash the sound barrier.

A Trekkie herself, Weitekamp completed a research fellowship at NASA and worked as a professor of women’s studies (she taught a course on the history of space travel) before coming to the Smithsonian in 2004. She helped organize the museum’s three days of events commemorating Star Trek’s launch, from Thursday’s showing of the pilot episode to Friday’s free “Boldly Go 50” celebration and costume contest, with guest speakers and documentary screenings (screenings are now full but the museum is offering standby tickets). It wraps up on Saturday with a sold-out cocktail party in the Smithsonian’s gardens surrounded by otherwordly botanicals. Washingtonian spoke to Weitekamp on what Star Trek tells us about the history of space travel.

So you are the curator of the social and cultural dimensions of spaceflight. What role does space travel have in our, well, society and culture?

It’s something that Americans have been fascinated with since it was just the realm of fiction. Space flight taps into fundamental ideas about who Americans believe we are, our sense of national identity as explorers, inventors, people with the ingenuity to solve problems. It has been an important part of Americans’ identity in the world, too. In the ’70s and ’80s, after space flights, there would be a world tour of the spacecraft and the astronauts to demonstrate what the US had done.

In the documentary Building Star Trek, which will be shown Friday, you say that the Starship Enterprise model deserves to be in the Smithsonian alongside other—real—spaceships and aircraft. Why?

I spend my job thinking about what real space flight has meant for American culture and the world, how we have remembered that through physical things, and how we have imagined how space flight could be through television, books, and movies. Some of the really important stories the Air and Space Museum has always told are not only the stories of these technologies and the people who built them and flew them but the inspiration and imagination that goes into making those real things happen.

If you talk to earlier astronauts, they say as kids they wanted to fly. They built model airplanes out of balsa wood and were often fans of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon. And if you talk to folks who work at NASA now, many are fans of space science-fiction, because it’s a vision of the kind of things they’d like to be doing. There are crossovers of influence between fiction and reality. If we were going to put one signature piece to bring out themes of imagination and inspiration, the Enterprise is a great example.

Whether they’re coming as Star Trek fans or just everyday museumgoers, what do you hope viewers take away from the exhibits?

Part of what we are trying to do when we put objects on display is create a juxtaposition that gets you to look at them in a slightly different way. Hopefully entering the Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall makes you think about the connections between the way space flight has been imagined and what’s going on in that hall.

Compare the Enterprise to the Apollo Lunar Module. Those were things that were on the drawing board at the same time. Creators of the fictional piece and the real piece threw out everything that had been known about what a spaceship would look like, the assumptions that it would need to be streamlined or a pointy rocket or a gumdrop-shaped thing. They thought about how you would you design something for a specific mission. If it would never fly in an atmosphere, it would never need to be streamlined.

What can attendees expect from special guest speakers at this week’s events? For example, Bjo and John Trimble, billed as two of Star Trek’s founding fans?

I am really excited that we have Bjo and John Trimble. These are the folks who, back in the 1960s, organized the write-in campaign that got Star Trek its third season. So really it’s thanks to them that we’re here celebrating this anniversary, because without the third season, you don’t have enough episodes to go into syndication, and that’s where the series really took off—being shown in syndication and reruns. And in another example of the link between imagined and the real, the Trimbles later led the write-in campaign to NASA to name its first space shuttle test vehicle Enterprise instead of Constitution. People wrote in to the Ford White House and NASA and they ended up renaming the space shuttle.

If you were to enter the costume contest, who would you go as?

That’s hard. You go back and forth between wanting to do a classic Uhura or Nurse Chapel in a ’60s mod, funky dress, and wanting to go Captain Janeway, and get something from that.

I will probably not be in costume. I tend to have an anthropologist’s perspective on this: it’s something I both participate in and study. I have a 50th anniversary Star Trek pin, though, that will definitely be on my lapel.