The National Gallery of Art’s East Building reopens on Friday after three years of renovations. It’s more than worth a visit—and a climb to the top floor.

The structure asks for its visitors to gradually make their way up from the bottom, moving from the Gallery’s earliest acquisitions like the paintings of French Post-Impressionist Pierre Bonnard to its contemporary work, such as Janine Antoni’s much fussed over “Lick and Lather,” a series of busts composed of chocolate and soap. The bottom floors offer a more traditional viewing experience: small taupe-colored rooms leading to more small taupe-colored rooms. As one moves upward, however, the spaces open up, offering more dramatic and artful exhibition rooms. The largest single aspect of the I.M. Pei-designed building’s renovation has been the addition of a roof terrace flanked by a reimagination two of the three original “tower” rooms of Pei’s design.

On one side is a space dedicated to sculptor Alexander Calder, with gently spinning mobiles of all shapes and sizes delicately cascading from the ceiling. The subtle movements of the fine wire pieces mimic the effect of a slight breeze through wind chimes—it’s both relaxing and slightly mesmerizing, especially when we’re used to art that stands stock still. Delight is a relatively rare emotion to emerge in a museum, making it all the more compelling.

But it’s the tower space on the other side—a divided hexagonal room—that caused several visitors to gasp as I surveyed it. On one side of the division (the room you enter from the roof terrace) hang Barnett Newman’s fourteen “Stations of the Cross,” the human-sized renderings of secular suffering and pain conceived in conversation with the Bible story. Entirely black and white, with just a tinge of red in the final painting, the series wraps around the viewer, fully encapsulating you in the small but meaningful differentiations between paintings. Hung as a series, the paintings gain a narrative they might otherwise have lost.

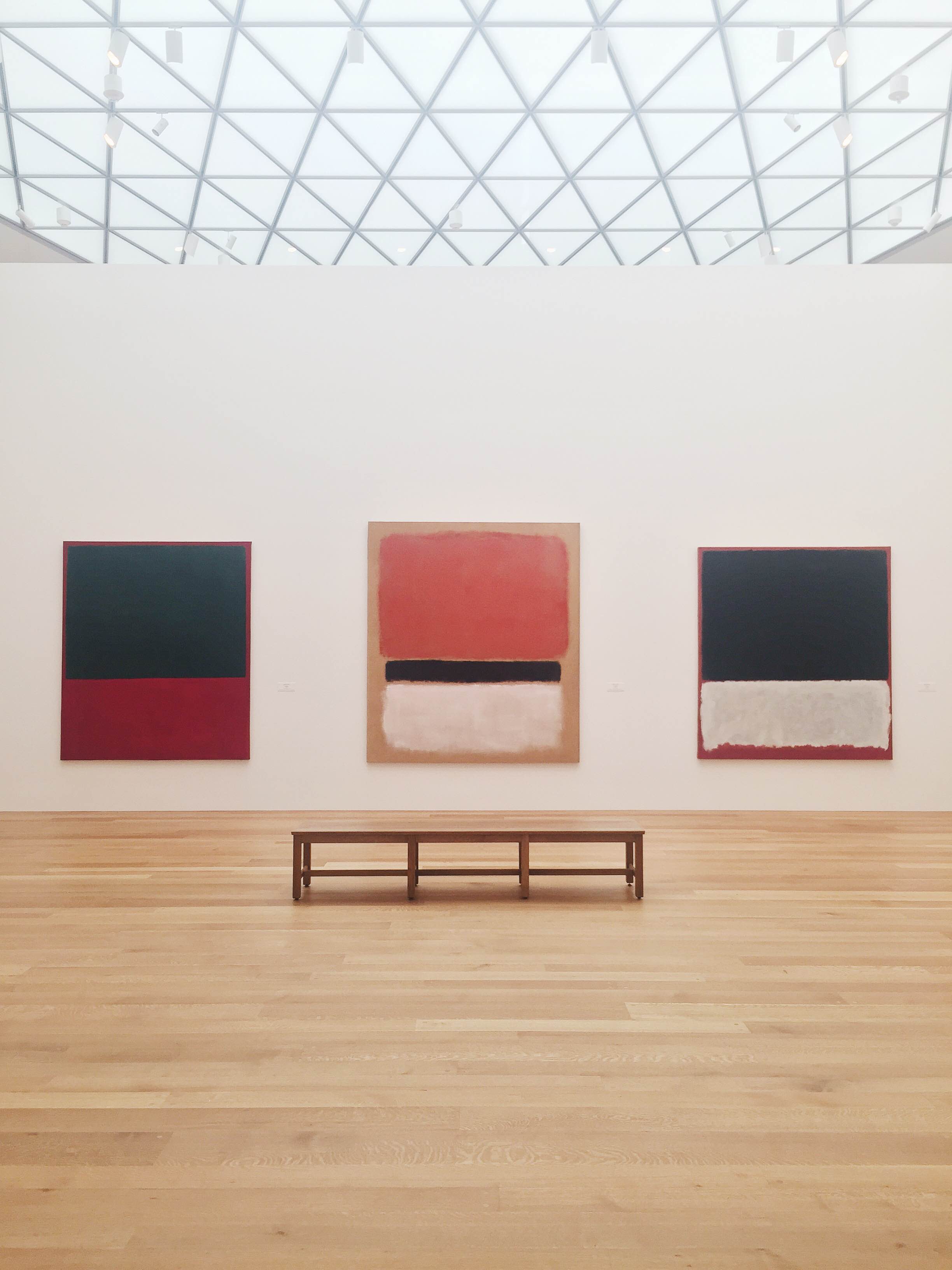

The light edging around either side of the room’s division invite the viewer to move from Newman’s chiaroscuric works, which require you to move from painting to painting searching for the scene in each, to a mirror image of that space covered in Mark Rothko’s giant, glowing canvases, which require the viewer to step back and attempt to take in the sight of so much hazy, vivid color all at once. The dichotomy is stark, and yet the paintings all work together somehow, rather than one set repelling the other.

With light filtering through the glass ceiling above, the tower room does feel like a crescendo of sorts, but not in the way many museums’ most famous or valuable pieces often do. The room isn’t dedicated to ensuring that visitors snake their way into the belly of the museum, to first be captured and then let out through the gift shop. Instead, it’s a reminder that in a space dedicated to honoring the modern and the contemporary that the evolution of art remains just as integral as any singular Marilyn Monroe by Andy Warhol or Donald Judd aluminum box. There’s still a story in abstract art.