It wasn’t actually a swamp. But it wasn’t a city, either, which pleased those Founding Fathers who were suspicious of big-city culture. A deal got cut: Uncle Sam absorbed states’ Revolutionary War debts, a move many Northerners wanted. In exchange, the Southerners got the capital.

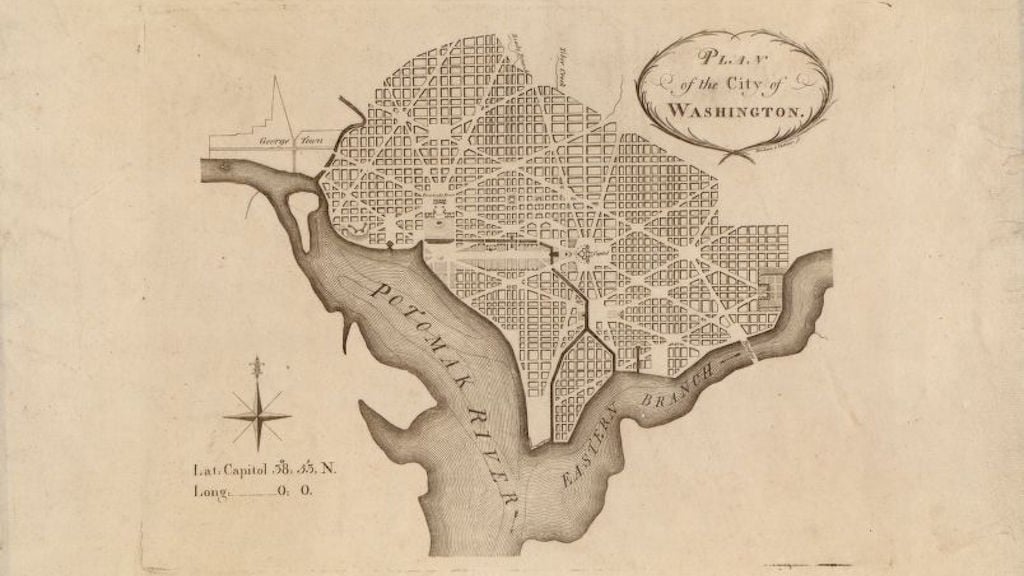

A Frenchman named L’Enfant was hired to draw a map worthy of an empire. But the government wouldn’t spend on its capital; most of the grand avenues existed only in name. After the British burned the place in 1814, there was serious talk of not rebuilding.

A few decades later—with the Capitol dome still unbuilt—the formerly Virginia parts of DC left. This was partly because Congress wouldn’t invest in facilities, but also because America was increasingly polarized over slavery. Another deal got cut: No more selling humans here—but owning was still okay.

The population boomed during the Civil War. Afterward, the District elected a governor who did things like pave and light streets, something that in muddy DC was a big enough deal that “Boss” Shepherd remains a local hero even though he got run out of town over finances.

During the Gilded Age, the government became an actual civil service that hired on merit, which decreased the revolving-door-of-patronage-hacks factor and also made Washington an attractive place for African-Americans moving north. In the 20th century, that government swelled, spurred by the Depression and World War II. (The New Deal also landed DC a slew of memorials.)

Like most wars, the Cold War was good to Washington. Most of the growth took place in the burbs, aided by the brand-new Beltway and Metro. After the 1968 riots, DC’s population stalled, a product of white flight. The spectacle of a majority-black population with no voting rights became a civil-rights issue.

After home rule arrived—with a bunch of maddening loopholes—DC had a political culture pretty typical of 1980s cities. There were shiny new developments downtown. And, in the neighborhoods, a sense that the bloated government wasn’t up to fighting crime and drugs. Mayor Marion Barry himself got caught in a bust. The government went bankrupt even as the region’s economy thrived. There were jokes about the last one out turning off the lights.

But a funny thing happened. A bunch of new populations found that this was actually a place they wanted to live: gay people, creative-classers, immigrants, folks sick of sprawl. The population grew a bit in the ’90s. It grew a bunch in the 2000s. Nowadays, it adds about 1,000 a week, many of them upscale types who have fueled a boom in condos and fancy eateries—and deep concerns by those who feel left out.

Right now, the prediction is that DC will have 800,000 people by the next decade. We worry about where they’ll live and whether they can afford the rent. But if you’re a newcomer who’s been house-hunting, you know that. You’re part of our history now, too.