Things started to go wrong at the seventh row of the silver and magenta beehive. The collective weight of the heavy tubes caused them to lean in on themselves. The rows were getting more and more difficult to stack up, and the builders had to improvise. They were running out of time.

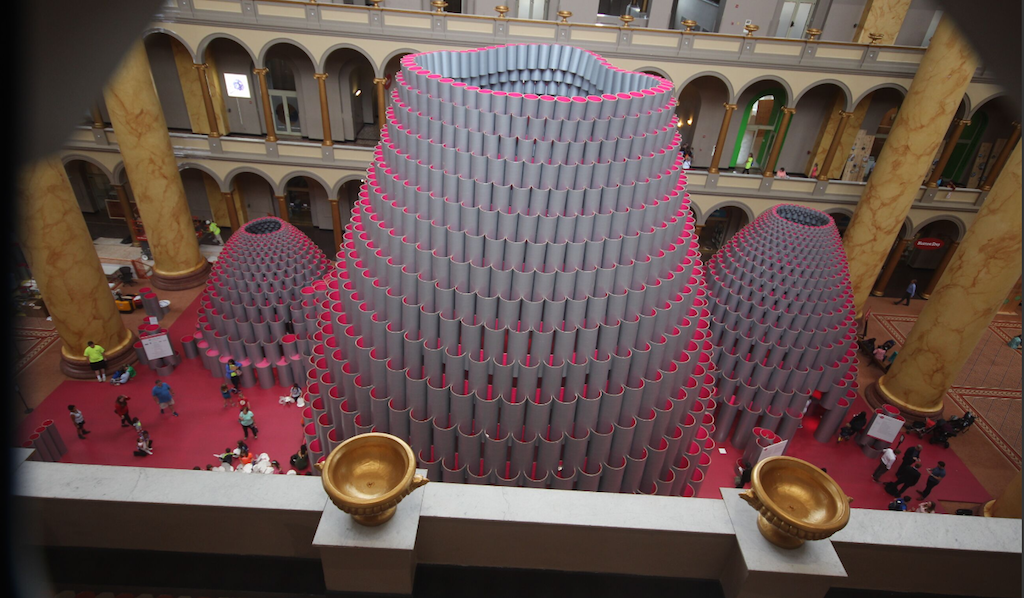

This was just one of the problems that came up during the construction of Hive, the National Building Museum’s latest Summer Block Party installation. Designed by Chicago’s Studio Gang, the structure is the tallest ever to be installed in the National Building Museum. The oculus of its highest dome was designed to top out at 60 feet when completed, but it never got there. It now stands at around 50 feet, and that’s the highest it’s going to get. The two smaller domes are completed as designed.

The Building Museum’s master carpenter, Chris Maclay, says the designers didn’t account for the weight of the Sonotubes, which are usually used for pouring concrete to build columns in parking garages and other large structures. The biggest tubes weigh 200 pounds. The entire structure is 72,960 pounds.

“The nemesis of this is: The materials we’re using are building materials never used in this arena,” Maclay says.

So although head architect Jeanne Gang and her team performed stress tests on the tubes to make sure they wouldn’t crush, they didn’t plan for how much they’d lean inward. They also engineered the structure using a computer system, which doesn’t always translate to real-life construction scenarios. “Prototypes don’t always work,” Maclay says.

In order to keep slotting the tubes on top of one another to complete each row, Maclay and his team had to ram scissor lifts into the side of the installation like elephants to keep them from leaning. At one point, they strapped 24-foot ladders onto the lifts so they could reach the higher rows.

“We put out calls to King Kong and the Hulk,” Maclay jokes. “No response. ”

Their other nemesis was time. The team had only three weeks to finish the hives, and that included a bunch of prep work. Carpenters had to cut more than 20,000 slots in 2,500 tubes. In total, the team worked more than 2,000 hours in three weeks to get as far as they did.

When Maclay and team reached the 16th row, they decided they couldn’t go any farther. On the day before the exhibit was set to open, Maclay got on a conference call with Gang and her engineer. Gang initially pushed back against the idea that the biggest dome couldn’t be completed. She suggested building scaffoldings to support the sides as they went higher, which would cost around $50,000 and take more than two days to set up. After Maclay explained the impossibility of it given the time frame, she accepted the sculpture would open incomplete.

During a media preview of the exhibit on Monday, the Building Museum’s Executive Director Chase Ryn told Washingtonian writer Christine Jackson, “Now, as you can see, ‘Hive’ is still undergoing the final stages of construction, demonstrating how complex and challenging this engineering feat has been to accomplish in a very, very short amount of time. I should note that it is not unusual for our visitors to encounter the sounds and sights of construction of our various exhibitions, which is fitting to our mission to educate people about design and the building process.”

Maclay says the Summer Block Party installations are always tough to finish, but this is the first time they actually ran out of time. “This is also part of the story,” he says.

Video courtesy of Work Zone Cam.