Paul Yandura and I are cruising through Appalachian farmland on his ATV, mud spraying, twigs smacking the windshield of the camouflage four-wheeler. Over the roar of the engine, he’s talking up his latest business venture. The motor is no match for his full-throttle voice or sonic-booming laugh.

Even though today is gloomy and damp, Yandura is describing only sunshine here amid the West Virginia pastures. He envisions an “eco-resort” on the banks of the Cacapon River, with sweeping views of the Great North Mountain ridge. Someday soon, people from Washington—people like him and the other business owners who have flocked to the town of Wardensville since he and his partner, Donald Hitchcock, opened a boutique there in 2013—will be kayaking on the clear water.

Yandura describes the eight modern, glass-box cabins he’s going to build, “like what you’d see in Dwell,” plus a lodge with a restaurant, maybe a spa. Road-trippers from DC, just two hours away, could stay for about $300 a night—ATV included. “Not one of these, but an electric one,” he yells. “They’ll probably still be camo because I think city folks will be like, ‘I got a camo cart!’ ”

It might sound rather formidable, here in a sleepy farm town with a church for every 50 residents: a duo who until recently were one of DC’s leading gay political power couples, turning a deep-red corner of Appalachia into a magnet for weekending Washingtonians? But it’s not so far-fetched once you get to know them.

It started with an old feed store that came up for sale in 2013. Hitchcock and Yandura bought it and turned it into the Lost River Trading Post, a hybrid coffee shop, art gallery, and home-goods store. They also bought the house next door, moved in, and raised a gay-pride flag out front.

At the time, Wardensville, population 250, was a place Washington types mostly passed through.

The next stop over is Lost River, a mountainous enclave that’s long been popular with gay DC weekenders. But now the Trading Post, with its prime spot at the entrance to town—plus the fire-orange cow statue the couple parked out front—beckoned those travelers to stop.

Many who did so came away with more than lattes and artisanal soy candles. They also got a pitch from Wardensville’s unofficial evangelists. And if Yandura’s boisterous approach wasn’t their thing, maybe Hitchcock’s low-key drawl would hook them.

They’d tell recruits about the Wardensville Main Street Initiative, a group they started in order to lure other investors. They’d explain how their organization was a real support system, run by grownups who knew what they were doing. Thanks to his political past life, Yandura has a knack for finding grant money and connections within the federal government to help rural businesses get off the ground.

He and Hitchcock also became real-estate agents. Which means potential transplants need only hop into their Land Rover to get zipped around to the mountain houses with the best views and the shuttered 1800s storefronts with the most potential.

It has worked. Marine turned FBI agent turned security consultant Patty Haley stopped into the Trading Post for coffee in 2015 and left convinced that she should trade Alexandria for a fixer-upper on Main Street. She started out renting two Mongolian yurts in her yard on Airbnb and has since become the town’s female-empowerment coach, teaching self-defense and belly dancing at a local barn.

Another FBI veteran, Dave Altenburg, bought a building he rents to a company that specializes in transcribing congressional and federal-agency hearings—remote work that can be done much more cheaply from West Virginia than from DC. Elizabeth Pennell, who runs the business, says she’d often stop by the Trading Post, and at every visit—four years running—“Donald and Paul were always like, ‘When are you going to open up an office?’ ”

Sally Weaver, an analyst at SpaceX who lives in Springfield, bought a rundown motel earlier this year after getting to know the couple while passing through on her motorcycle. “It was kind of kismet, really,” Weaver says. She always wanted to buy an old motel and transform it into something modern-rustic, so that’s what the new Firefly Inn will become.

Vicki Johnson, a former government lawyer who met Yandura when they both worked in politics, watched him post on Facebook about his new life in the country. After she inquired, he wound up finding her a log cabin in the mountains and showing her a vacant Main Street building. She promptly “fell in love,” opened a vintage store called Lucky Johnson’s, and hung the town’s second gay-pride flag. The list goes on—nearly two dozen businesses and nonprofits have opened in Wardensville since 2013.

“Change can be scary for anybody,” Johnson says. But “Paul and Donald were already here, and they were great mentors.”

In one of the most depressed states in the Union, you might assume that the economic jolt would be welcomed as great news. But as city folk turned country gentlemen learned long before the rise of Donald Trump—who, by the way, got 76 percent of the vote in Wardensville’s county—fitting in with the locals is rarely simple.

Yandura and Hitchcock have been screamed at, had their property vandalized, and, well, worse. “I mean, we got our gay people out here. But they’re not puttin’ it out in your face,” says lifelong resident Joshua Frye, whose family settled in the area in the 1700s. Frye runs a 600-acre farm and cutting-edge agricultural operation that turns chicken dung into fertilizer. “I don’t wanna see two guys holdin’ hands. I don’t wanna see a guy and a girl makin’ out, much less two guys or two girls.”

These days, Main Street might be brightening up. But turn onto the dirt back roads and you’ll still pass trailers hoisted on cinder blocks and Confederate flags planted in front yards. Spend five minutes in a town-council meeting for a taste of some seriously nasty local politics. A lot of it—directly or indirectly—involves Yandura and Hitchcock.

As Yandura puts it, there have been days when Wardensville felt like living in the nuttiest Facebook comments thread. “But it’s for real! It. Is. Real.”

To truly understand the case against new Wardensville, you have to meet the town’s former power couple, John Sayers and his wife, Betsy Orndoff-Sayers.

John was town recorder—basically, treasurer—for more than 20 years. Betsy descends from the Wardens, for whom the town was named in 1832. Together they own the Star Mercantile, a general store and restaurant that occupies one of the oldest buildings on Main Street. “The new group got in immediately and said everything the old group did was crap,” John says.

On the surface, Sayers is mostly talking about Barbara Ratcliff. A 73-year-old widow with bright-white hair and pink-tinted glasses, Ratcliff moved to town 16 years ago after retiring from a packaging business in Prince William County. Impressed with Yandura’s business boosterism, she asked him to help run her campaign for mayor. Not withstanding her Republican affiliation, he obliged. Soon he and Hitchcock were her biggest supporters, the three of them traveling to the state capital to tout Wardensville’s progress and to lobby for funding.

Even though Ratcliff ran unopposed, her ascension sowed deep resentment among residents who felt steamrolled by what came next. Moving to right Wardensville’s floundering finances, Ratcliff, among other things, did away with the town police. She brought in state auditors to go over the books. The attorney general’s office got involved and filed court papers that blamed Sayers and a fellow official for taking out “an unlawful line of credit” to pay the bills.

Sayers says he knew the credit line was “outside the realm of appropriate government accounting, but there’s just not a whole lot of funding streams available to local towns. . . . I thought it was one of those things towns do to get by.” He believes that Ratcliff wanted him “locked up,” and he has no shortage of fury for her administration. “It’s her way or the highway,” Sayers complains. “You can’t run a town like you’re Baby Doc, like you’re Putin—you can’t do it.”

With their ally cast as a dictator, Yandura and Hitchcock’s growing role in Wardensville took on an even more sinister image in the eyes of some old-timers like Sayers.

It was far from the only time Wardensville’s political tensions and its new power duo collided. At her church, people told Ratcliff they didn’t like her associating with gay people. “I am a religious person,” she says. “But God made everybody, right? And he loves everybody. They didn’t agree with me, and I just felt it was better that I no longer went there.”

I don’t wanna see two guys holdin’ hands. I don’t wanna see a guy and a girl makin’ out, much less two guys or two girls.

Soon after her election, someone began posting Ku Klux Klan crosses on the bulletin board near town hall. A different white-supremacist group left behind membership applications. Ratcliff says she called the FBI—“they came out and cruised around for a few days”—and the postings stopped.

Town-council meetings turned into monthly showdowns over whatever Ratcliff proposed, with the mayor’s partisans occupying the front rows while her haters took the back—yelling questions and sometimes making a show of storming out. “It was ‘Shut up,’ ‘No, you shut up,’ ” says one attendee of a particularly intense meeting last December where Donald Hitchcock got in the middle of a shouting match between Sayers and the mayor.

The ordeal devolved into a high-school staring contest. “You wanna go outside?” Sayers asked Hitchcock, who ignored him. Sayers moved to the front row and sat beside him. Hitchcock did him one better—he leaned in toward Sayers and snapped a selfie.

The disgruntled natives began trolling the new in-crew online, in a Facebook group run by an anonymous administrator and sarcastically named Good News Wardensville.

In the snarky lexicon of its users, Ratcliff was nicknamed Good Old Mayor; Yandura and Hitchcock were the New Friends. Joseph Kapp, another gay DC transplant and Ratcliff supporter, owns a building on Main Street where aspiring entrepreneurs can test out business concepts. He was ridiculed on the site as the Wiz of Biz. (Catchy name, Kapp thought—the Wiz now travels the country in a green top hat and cape, speaking about entrepreneurship for thousands of dollars an appearance.)

Some attacks were darker. After Yandura and Hitchcock got the land for their eco-resort on the Cacapon River, Good News Wardensville trolls made threats. “I can’t wait to see how many people come up missing because they are trespassing on people’s property,” wrote one of the page’s regular commenters. “Obviously they’ve never seen the movie ‘Deliverance’. If Ned Beatty couldn’t make it down a river in one piece, a Gay guy from the city don’t stand a chance.”

Offline, the rancor got just as ugly. There was the time a woman barged into Hitchcock and Yandura’s store, ranting about how they were “dredging the river”—a point of anxiety among locals who believe the couple will somehow make the river accessible to larger boats (filled with outsiders). An employee called Yandura, who raced over in time to jump into his truck and follow the woman home so he could explain. When he got there, Yandura says, her two dogs penned him in his vehicle.

On another day, county police showed up at the store—because someone had reported that Yandura and Hitchcock kept child porn inside. Yandura says the officer was nice about it, said he had to stop by even though he knew the call was bogus. But still.

Yandura and Hitchcock’s efforts to beautify the town didn’t make things better.

Consider the White Lights Affair. Back when Main Street was “scary and dark,” says Hitchcock, the couple noticed that if they left the lights on at the Trading Post, they’d get customers the next day who’d seen the shop at night. The obvious move—more lights. So they hung strings of white LEDs outside the store and along the fence of the cemetery across the street and encouraged others to do the same.

Within days, Hitchcock and Yandura awoke to find the lights on the cemetery fence unplugged. Then it happened again—and again. Annoying but not too big a deal. Until someone cut them. “Four hundred dollars’ worth of lights,” says Hitchcock.

Nearly two years later, the episode clearly still rankles John and Betsy Sayers, but for a different reason. “They said the whole town should put lights up—the white lights up—that it makes us look like a special little place,” says John.

“I wanna say they wanted to call it Little Washington or Little Georgetown, like Little Alexandria,” grumbles Betsy.

Yandura and Hitchcock don’t scare easily. They got over being the outsiders long before they set foot in Wardensville.

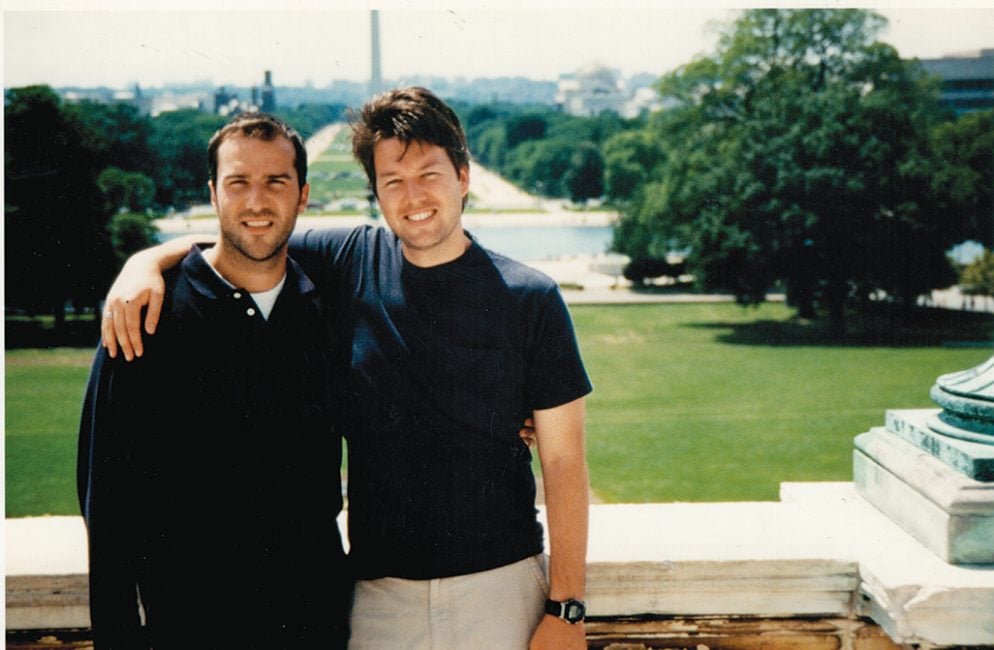

Yandura, now 48, grew up in a working-class family in Detroit. Hitchcock, 44, was a military brat in rural Florida. The two met in DC in the mid-’90s when Hitchcock was working for the founder of the Gay and Lesbian Victory Fund and Yandura was ascending the Clinton White House.

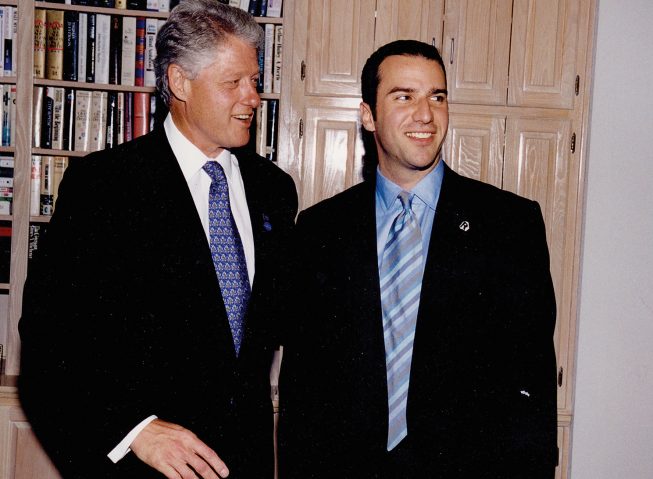

At his orientation there in 1994, Yandura was the community-college kid surrounded by Ivy Leaguers. When a staffer asked if anyone in the room was gay, he was the only person in the crowd of 200 to stand up. He thought he’d be kicked out. It turned out the President wanted to form a gay-and-lesbian outreach office and needed someone who was actually gay to help.

“This is my first f—ing day!” says Yandura, his eyes as wide as tractor tires. “I remember calling my mom and going, ‘Here’s what happened. I met Bill Clinton. Because I’m gay!’ It was the craziest.”

He later became the gay-and-lesbian outreach director for the President’s ’96 reelection campaign, then raised millions from the LGBT community for the Democratic Party. Eventually, he started a political fundraising and consulting firm with another ex-Clintonite.

Yandura (left) and Hitchcock met via Democratic circles in the 90s.

Yandura (left) and Hitchcock met via Democratic circles in the 90s. At the time, Yandura was working in the Clinton White House.

At the time, Yandura was working in the Clinton White House. They went on to become some of the party's most powerful gay operatives.

They went on to become some of the party's most powerful gay operatives.But the more entrenched he got in the party, the sicker he felt about “covering the ass” of candidates who took money from gay supporters without standing up for them. In 2006, he fired off an e-mail to major gay donors imploring them to close their wallets until the Democratic National Committee started pushing for their rights. At the time, the DNC’s gay-and-lesbian outreach arm was run by his boyfriend—Hitchcock.

Yandura’s e-mail quickly leaked. Within weeks, Hitchcock was fired. He sued for defamation and claimed that his dismissal was retaliation. What followed became an embarrassing spectacle for the party. Then–DNC chairman Howard Dean was deposed during the 2008 primaries, and discovery yielded unflattering internal e-mails. Hitchcock became a political pariah and started selling medical devices. (His lawsuit was eventually settled.) But Yandura continued agitating, becoming a ringleader for a group called GetEqual to put pressure on President Obama. Its activists chained themselves to the White House fence and crashed Obama’s speeches.

One of their most memorable stunts took place in October 2010, when the fight to repeal Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was at full bore and Obama wasn’t, in their view, acting quickly enough to get rid of it. They caught word that retired basketball player Alonzo Mourning was planning a fundraiser for the President at his waterfront compound in Miami. Yandura, Hitchcock, and fellow activists motored two boats to a spot facing Mourning’s property, where Obama was speaking in a white tent. They unfurled 40-foot banners (WE’LL GIVE WHEN WE GET EQUAL, one said) and chanted over the sound system while blasting air horns. Coast Guard officers with machine guns zoomed toward them, but Yandura had a lawyer on the phone who asserted the group’s right to protest. Two months later, Obama signed the law ending DADT.

“Why do you think the gays got everything they wanted?” says Yandura, reflecting on those years. “I call it the funnel. You jam [the opposition] down that funnel, and you don’t let them turn around. They’re like, ‘This isn’t fair! Why are you making it personal?’ You say no, and you just keep jamming until they’re so deep in the funnel that they’re like, ‘Oh, my God—I’ll just do it.’ ”

But the funnel proved tricky in Wardensville, where not everyone has Yandura’s tolerance for conflict. This past spring, Ratcliff grew exhausted by the animus she’d faced since running for mayor and resigned as a new fight over the town’s public utilities was escalating. She says she regrets that her tenure had to end that way, but she’s happier now. More time to knit.

These days, Yandura and Hitchcock are no longer limiting their agenda just to building up the town’s business base. The couple’s latest project is all about do-gooding—albeit the kind that may not thrill some of Wardensville’s old-timers: They want to turn the place into an “agrarian community” and foodie destination that would put local kids to work.

In 2015, Jonathan Lewis—heir to the Progressive Insurance fortune, a major donor to gay-rights causes, and a longtime friend of Yandura’s who funded GetEqual—bought land for the project. Last year, Yandura and Hitchcock opened the Wardensville Garden Market, a farm and bakery where 20-some local youth have jobs learning how to grow and sell organic produce, as well as life skills such as how to manage their $9-an-hour paychecks. Lewis has put more than $1 million into the program.

The next step: hashing out a deal that could transform the farm from a heartwarmer with small-scale impact into a high-wattage attraction with the potential to bring more people and money to town. They’re working on a possible partnership with DC restaurateurs Paul Cohn, co-owner of Boss Shepherd’s downtown, and Rob Wilder, business partner to Washington’s most famous chef, José Andrés.

Yandura, Hitchcock, and Lewis envision opportunities for the Wardensville teens to work in high-end Washington eateries and, on the flipside, a chance to bring city kids to Appalachia. The 150-acre property has room for kitchens, educational and meeting space, and housing where the students, visiting chefs, and other out-of-towners could stay during special dinners and events. Eventually, there’d be a farm-to-table restaurant staffed partly by the young trainees. All of it would be built on the same riverfront land once slotted for the Dwell-style eco-resort, which means that’s on hold—Yandura and Lewis say it makes more sense to make Wardensville a destination, then put up lodging.

So far, the teens who signed up to work at the farm have all stuck with it. “I love it here—we can be ourselves,” says 16-year-old Ethan Combs. “Before, I wasn’t very talkative at all. This place gives you a certain type of confidence.”

But given who the farm’s backers are—successful men with cosmopolitan views—it’s also a hearts-and-minds campaign. “It goes beyond ‘let’s grow vegetables,’ ” says Lewis. “These are life-inspiring experiences.”

In fact, Yandura and Hitchcock say much of Wardensville has already been welcoming. When Tricia Scott’s late husband got sick and decided to sell their home on Main Street, “he wanted them to have it,” Scott says. “He knew that if Donald and Paul got the house, it’s not just going to deteriorate like the rest of this town.” Lorraine Link, a waitress at the Kac-Ka-Pon Restaurant, a Wardensville institution dating to the ’60s, says business has “gone through the roof” since Yandura and Hitchcock arrived. She’s not bothered one bit by the fact that they’re gay, she says: “Because I have a daughter who’s married to another girl.”

Already, the farm has drawn visits from officials including US senator Joe Manchin. It’s also become a favorite stop for the Lost River weekend crowd, no doubt enticed as much by its made-for-an-Anthropologie-catalog aesthetics as by its pristine, pesticide-free veggies.

But as always, it’s complicated. Kids who work there say a lot of people remain suspicious of the place. “Just because Paul and Donald are gay, so many people are against this,” says Combs. “We had churches pull down our fliers.”

“It makes me so mad,” says one of his female coworkers. She volunteers that her dad doesn’t like gay people but that her own thinking will never match his. “I’ve met them. I’ve given them a chance.”

Though the town’s younger denizens have come around, Yandura and Hitchcock likely haven’t seen the last of the old-versus-new culture clash that has followed them these last four years—especially if their plans to build out the full “agrarian community” come through.

As Joshua Frye points out, the farm has a prime spot on the Cacapon River, a public waterway that locals nonetheless like to think of as their own. “I don’t like people building up along the river,” Frye says as we talk in his 100-year-old kitchen, where a hand-crank phone hangs next to a cast-iron, wood-burning stove. (Elsewhere on the property, there’s a slave graveyard.) “I just know the more people you put on the river, it’s not a good thing.”

There’s an environmental toll to consider, he says. But worse, there’s the prospect of out-of-towners coming onto locals’ property. “I’ll get pretty ugly over that,” he says. “There’s gonna be a lot of farmers down here that’s gonna go el nutso over that.”

Senior editor Marisa M. Kashino can be reached at mkashino@washingtonian.com. On Twitter, she’s @marisakashino.

This article appears in the July 2017 issue of Washingtonian.