One muggy and overcast morning in June, my friend Mike and I woke up at dawn, in a hotel room just south of the Mixing Bowl in Springfield, and walked due east along Franconia Road until we hit Van Dorn Street, where we joined (and, for a time, outpaced) a slow-moving horde of Beltway-bound commuters in their cars.

As a kid growing up in DC, I had heard names like this on WTOP all the time—Van Dorn Street, St. Barnabas Road—and I’d certainly whizzed by this very spot in a car a few times. But I’d probably never turned my head enough to notice that Van Dorn gains a high prospect just before it tucks underneath the Beltway, and that if you stand at that height for a few moments near the peak of the morning rush and watch the cars crawling toward the city and racing around it, you can almost find the whole thing beautiful. Almost, and in a relative sense: It was just a bunch of cars commuting on a hot morning in an actually-not-very-scenic location, aside from the visual relief of the hill.

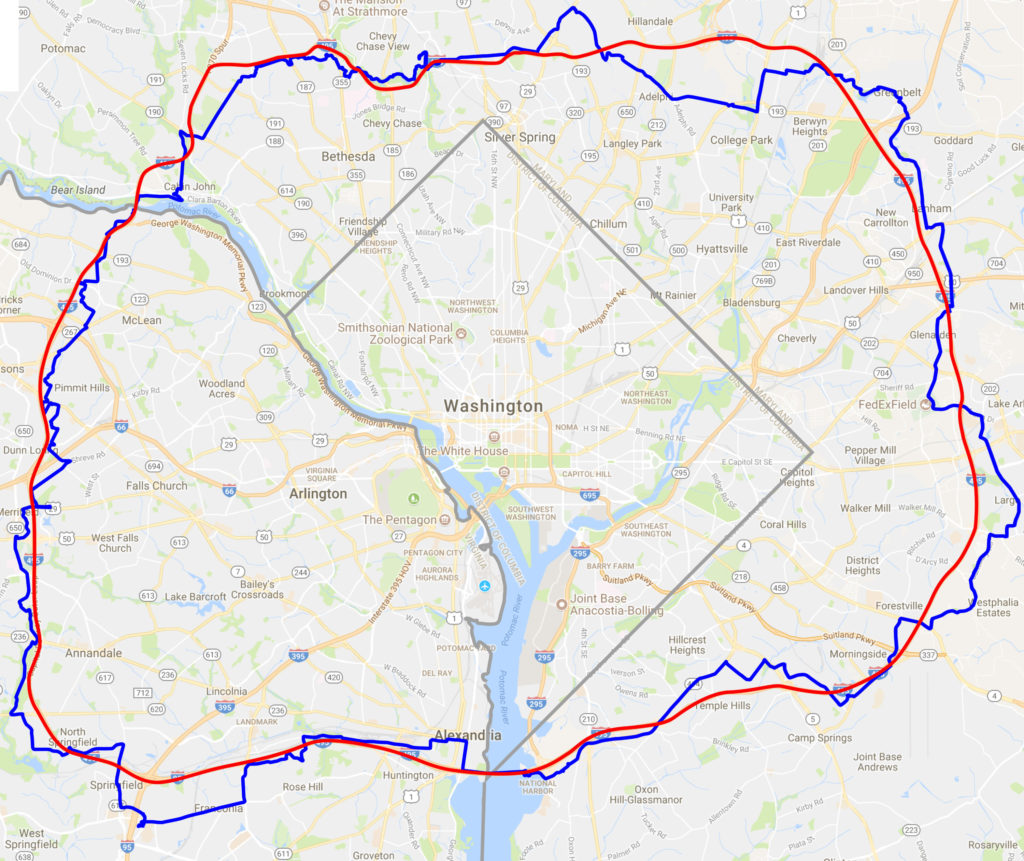

Part of it was that we had walked 21 miles the day before, from Gibbons Roost on the shore of the Potomac in McLean through Tysons, then all the way down to the great cloaca of the intersection of interstates 95 and 495, where we were turned away from two fully booked hotels and had to walk an extra embittered mile just to find someplace to sleep. And part of it was that this was our job: An editor had suggested an unlikely assignment—to hike the Beltway and treat it like the Appalachian Trail. Stay as close to the highway as we could, hike the entire 64-mile loop along surface roads (walking isn’t permitted on 495), and do our best to keep our eyes open along the way.

We took this particular scene in for a few moments, then got moving again. The route we had decided on that morning was to take Van Dorn under and inside the Beltway and then to link up with Eisenhower Avenue, which would take us through standard industrial tundra all the way to Alexandria. But as we approached on the east side of Van Dorn, Mike noticed a path leading into some woods just shy of the outer loop. It hadn’t shown up on our phones when we’d tried to piece together our plan for the day, but as we looked at the “satellite” view, it suggested that the path, if it was actually continuous, would keep us closer to the Beltway than Eisenhower would. We had already developed one ironclad rule—no extra steps—but we had also had a really good and tranquil experience on a path like that the day before. It would at least be quiet and shaded.

So without knowing exactly how it would end up but hopeful it wouldn’t set us back, we peeled off into the trees.

Why, exactly, two fortysomething dads—a writer and an artist—had decided to take on this challenge in the first place seemed clearer when it arose than it does now. Everybody we mentioned it to thought it was a great idea, as did we. We would experience a cross section of suburban Washington, from verdant idyll to industrial grit, and hope to learn something new about the city, or what surrounds it, in the process. Our utter lack of preparation married well with our hubris about what we could accomplish without said preparation, making the whole thing seem like a fun jaunt for which it would be a miracle to get paid.

Our goal was to stay as close to 495 as we could get (within reason), sometimes inside the Beltway and sometimes outside. As at Van Dorn Street, we still had to make decisions—things cropped up in person that weren’t on the maps—but the basic vision was to stay on foot, to buy any and all nourishment on the road (we didn’t even bring our own water), and for Mike to document our route through hourly videos, a GPS map, and photographs of everything we consumed while we were out. Then I’d write it up after we got back.

Simple enough. If the Beltway was 64 miles around, then surely we wouldn’t have to walk more than 75 to 80 total. A couple of miles an hour, eight to ten hours a day, and we’d knock it out in four days.

When we arrived at Gibbons Roost that first morning and scampered down the path to the edge of the Potomac, we were buoyed by the feeling of the whole thing. We were off! As we passed through the mansions and McMansions of McLean on our way to Tysons, we exuberantly went off-map, hunting through back yards for short cuts, steering clear of the omnipresent landscaping crews, and generally wasting energy in ways that would make us cringe a few hours later.

By the time we stopped for our first meal after about ten miles—at a Burmese joint called Myanmar off Route 29 in Falls Church—our feet were already blistering and our bodies were making it quite clear that this entire enterprise was going to demand a lot more of us than we had understood. Maybe it hadn’t been such a good idea to wear just running shoes and not to train. We pounded Advil over ginger and fermented-tea-leaf salads and tried to recalibrate our route and our expectations. When it was time to go, it took me what felt like 30 seconds to get out of my chair. Only six more hours to the Mixing Bowl!

All of this is to say that, as with any journey, and despite our best intentions, our trek rapidly became about us in ways we hadn’t predicted or wanted. The immediate and enduring depredations of the body became the overlay through which we began to view every decision we made, in addition to the other usual solipsisms.

A wise photographer once told me that the more uncomfortable you get, the better the story usually is, so here’s to hoping.

Most people ask the same questions: “Did you sleep in a tent?” No, there was nowhere to do that that didn’t smell like urine, and we have young families. We slept in hotels for two nights and at home the others. “How’d you get back to where you’d left off the previous day, if you went home?” Ride-sharing services, sometimes together, sometimes not. “Where did you eat?” Wherever we could that was directly on our route—an especially interesting prospect in that we were traversing a region whose demographics and tastes have been shaped by migrants from around the world. But there was absolutely no extra walking after the couple of off-route blocks to the Burmese restaurant on the first day.

Then, of course, the larger questions: “What did you see out there? What did you learn?”

One of the first things we noticed was that the areas through which the Beltway runs didn’t seem to have much in common before 495 existed, and in most places they still don’t. Though the Beltway was planned over decades and then built between 1955 and 1964, the communities that surround it tend to feel planned within their own enclosures but not as they relate to one another. Their only shared context is the highway that rumbles behind them, which led to some weird juxtapositions.

The weirdest was the one we encountered just after we left Van Dorn Street that second morning and headed into the woods. After a thousand meters on a wooded path, we emerged onto Oakwood Road, which was lined on its northern side with a bunch of small businesses—Suburban Fuel, Capital Printing, Lancaster Landscapes. Trucks and cars were parked at odd angles all over the place while what looked like teams of day laborers waited in the parking lots for their assignments. After just a few minutes’ walk, we saw a small gap in a hedgerow and skirted through it, emerging suddenly into a cul-de-sac in a seemingly spanking-new suburban enclave. We were standing less than a hundred feet from the jangle of cars and lots on Oakwood Road, but it was as if we had stepped onto a different planet. Two deer in a yard straight ahead picked up their heads but held still as we passed.

We proceeded to shuffle along the arrow-straight pavement of La Vista Drive, with identical houses along either side in a style we would come to recognize as Beltway Suburban Mullet—stately brick for the facade, vinyl siding the rest of the way around. Somehow, on this one small stretch of road, everybody was out in full force at 8:30 am: a man bringing a boxed lunch out to his daughter, who was waiting in the car; a tiny woman with her tinier dog, trimming the flowers on her front porch; an elderly gentleman in a recliner in a repurposed garage, now open-air and screened in, tapping away on his laptop on an elevated ergonomic stand.

Despite our best intentions, our trek rapidly became about us in ways we hadn’t predicted or wanted.

The comings and goings seemed almost orchestrated, as if we were inside a cuckoo clock or watching B-roll backdrop from American Beauty. Then, just two blocks later, everything changed into heterogeneous suburbia again, a change announced by a clapboard house on the corner that had a back yard full of beehives and a honey for sale sign on the front porch. Three distinct neighborhoods in less than half a mile, each so different from the others.

These juxtapositions appeared nearly everywhere we went, although sometimes the scale was different. On a long stretch of St. Barnabas Road in Prince George’s County, we paused briefly in front of a low-slung, heavily fenced house, with dogs barking in back, featuring a sign saying, we don’t call 911, we use guns. It sat next door to ABC Tumbling, 7 days a week early developmental child care.

By the end of the second day, it was clear both to us and to our unimpressed wives that there was no way we were going to finish in four days. We had done our feet in with our overreach on that 21-mile first day, and the concomitant adjustments to our gaits meant radiating discomfort up our legs for each of us, in different spots. Every morning from the third one on began with bandaging our feet and with a couple of other ablutions best left out of a family magazine. We rejiggered our route and decided to shoot for six days, instead of four, which seemed doable.

The third day was our second-longest, at almost 18 miles, and took us through some of the toughest terrain. Our lowest moment came that day when we had to make our way along and across Branch Avenue and later under the Beltway on Pennsylvania Avenue. There was very little shoulder on either road for much of the spans we needed to traverse, and the traffic volume was so dense and constant that we couldn’t afford to look at it as we walked, at times, with only a little more than a foot to occupy between driving lanes and a retaining wall. There’s a funny video of Mike trying to film me going through one such spot, only to fall on his ass before he could get anything incriminating. Those kinds of miles, in industrial areas or on uncovered roads with enormous numbers of cars flying past, took the most out of us by far. We became deeply thankful for the simple presence of sidewalks, for benches and shade. Bus stops came up huge.

Though we weren’t explicitly looking for it, there wasn’t much by way of beauty, even in the more rural spots. (The Beltway is farther out there than you realize—in Lanham, we briefly faced off with a chicken.) But there were definitely moments where we were so wrapped up in our natural surroundings that the miles slipped more easily beneath our feet.

On the first day, we walked an hour-plus along Accotink Creek and through Wakefield Park near Springfield, down long, tree-shaded alleys of path and gravel, almost entirely alone except for the hum of 495 to our left and an occasional biker. On the fifth day, during our walk from College Park to the Mormon temple in Kensington, we dropped down off Adelphi Road and onto a walking path next to the Northwest Branch, a stream that feeds into the Anacostia River, which we traced for more than a mile from inside the Beltway to well outside it, scrambling up and down rock faces in total silence except for the moment when we were under 495 itself. We caught a brief glimpse of a heron gliding over the Potomac as we set out on the first day and, on the second, a deer washing itself in the wide, slow-moving waters of Cameron Run, off Eisenhower Avenue in Alexandria, seemingly oblivious to the city just beyond the bank. But much of the time it was a grind—power lines overhead, discarded rusting razor blades at our feet.

Instead of the scenery, it was often the people who stood out: the young man who approached us as we left a 7-Eleven off Annapolis Road in New Carrollton and asked if we knew anybody who was hiring; the boy who ran out to us from a gas station on St. Barnabas Road to offer us discounted cleaning products, so young he could barely get the words out; the elderly woman outside a senior-living facility who watched us warily for a while near Pooks Hill Road off Rockville Pike, only to pull some shears out of her pocket and begin to snip at a rosebush in a way that suggested she wasn’t at all supposed to be doing it; the deeply committed man a few miles later near Fernwood Road, doing slo-mo martial arts on a residential street corner with a trainer; the senior-living facility on Franconia Road with a “special neighborhood for the memory-impaired.” That one stuck with me for a while.

We discovered that there’s an entire Camelot-inspired pocket in suburban Fairfax, featuring King Arthur Road (on which we walked), Guinevere Drive, Chivalry Road, Launcelot Way, Merlin Way, and so on. (The nerds involved in that naming process probably couldn’t believe their luck.) We stumbled across Greenbelt Lake and its accompanying park, a lovely respite full of kids zooming on their bikes hard by the Beltway. We scratched our heads in front of the Brazilian Aeronautical Commission’s warehouse on a random stretch of road in Prince George’s County, just up the street from a car-auction site and Dangerfield Martial Arts. Why is there even a Brazilian Aeronautical Commission, and why does it need a warehouse? (Turns out the facility ships modernized aviation equipment given by the US to Brazil.) This was all ephemera, in some sense, but that’s how it worked.

One of the cooler parts of being on foot was that we got to see some of the landmarks you associate with the Beltway from different angles. For as long as I can remember the “modern” Tysons, there has been that pink building with the semicircular articulations at the top—what turns out to be 8000 Towers Crescent, an office building. I remember riding past it all the time as a kid on my way out to I-66 with my family for soccer games, when the building was something of an outlier, before an entire city had sprung up around it. This time, we approached it almost without realizing it, from within the Beltway. We were deep inside a set of modest apartment complexes just off the inner loop when we looked up and there it was—that iconic crescent, right across the road from us. Before then, I’d never had the sense anybody actually lived in Tysons.

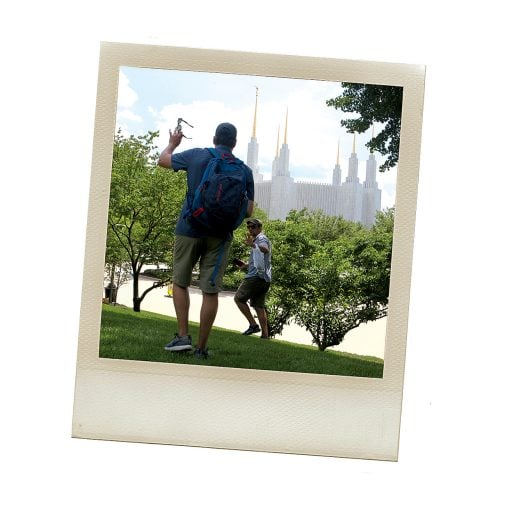

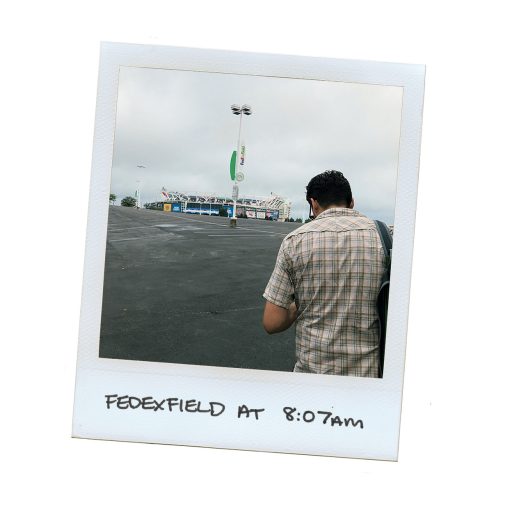

The same went for the Mormon temple, which we reached as a last straggling family of four crossed the empty parking lot to head to their car after Sunday services. For as long as I could remember, seeing the tabernacle from the Beltway meant I was home, but I’d never been on the grounds. At midday, you couldn’t avoid concluding that the building itself was lovely, glowing bright even against a bright summer sky. We also spent a lonely 15 minutes walking the barren lots around FedExField, where I’d only ever been drunk and disappointed. It was sort of wild to see it silent. Few buildings are uglier under those conditions, but it managed to be. (Our walk the previous day had already established for us exactly why and how an architectural disaster like FedExField stays in business: Prince George’s was flooded with more Redskins paraphernalia per capita than any other place I’ve ever seen.)

The one true moment of perspective on the actual city of Washington came when we crossed the Wilson Bridge over the Potomac and looked back up the river. It was the only time DC’s downtown and skyline were visible to us during our circuit, and from the bridge you could see how the city was nestled in the crotch of the Potomac and Anacostia rivers—in a way that made more sense from that vantage than from any other. As the bridge vibrated beneath our feet (much more than we had expected), we looked in toward the District and tried to imagine what it all had looked like before the city existed, when the port in Alexandria to our left was the biggest game in town.

But of all the landmarks, the one we got the biggest kick out of was one that was no longer there. On our third day, we decided to push all the way to Largo so we could wake up near FedExField and have a little less to do on the following days. I located a TGI Fridays—a personal favorite, don’t ask—on Google and a Courtyard Marriott across the street from it. It was a bit of a stretch, but we booked the room in advance to force us to get there and then went for it. Three miles out, a severe thunderstorm rolled in and we arrived at the restaurant tired and soaked.

Aside from being a dry space with food and cold beer after a long day, there were two great things about this particular TGI Fridays. The first was that—though I hadn’t known this when I chose it—it was on the grounds of the old Capital Centre, where I’d spent uncountable days and nights as a kid with my dad, going to Caps games. This cheered me up immediately. (My favorite player for several years was the relatively unknown Alan Haworth. Can’t remember why, given that Mike Gartner, Bobby Carpenter, Scott Stevens, and Rod Langway were all in the mix, but I’m sure I had my reasons.) It’s hard to argue against the new arena downtown, given all the development it’s driven and the revenue it brings in, but there was something irretrievably perfect about the old Cap Centre. The place had no pretensions; it was what it was. I can still see the main concourse and the variously themed parking-lot stanchions in my mind. You went there to watch sports and eat crappy pizza and wear your dad down until he got you some kind of tooth-destroying dessert. Then when the game was over, you waited for 45 minutes to get out of the parking lot, and you were okay with that—you always wanted to go back.

That same lot was now occupied by the TGI Fridays we had just walked into, which led to the second great thing: Somehow, through a combination of demographics, location, and circumstance, this particular iteration of an anodyne chain restaurant was kind of happening. Hip-hop was blasting, and the place felt vibrant and alive. People were having a good Friday night, maybe channeling the energy of the place that had once stood there. We both shuffled off to the bathroom for the relief of dry clothes and the chance to settle in for the evening. It was one of the best and most oddly authentic moments of the whole trip.

By the time we pulled off our socks and shoes at Azteca Restaurant on Route 1 in College Park, at the end of the fourth day, we weren’t in great shape. The skin had come clean off the pads of two of my toes, and my left Achilles tendon felt like it was going to pop. Mike was enduring similar discomforts, if more stoically than I.

The ride-sharing driver who took me home that afternoon, like most of the other drivers we had, just laughed and shook his head when I told him what we were doing. But he also took me home along the Beltway, the only time I spent on the highway itself during the entire project. It felt like a ride in a glorious, rule-defying spaceship.

When I got home, in a low moment of the soul, I pondered the possibility of postponing the final two legs of the trip for a couple of days to let our feet heal. But after some wine and a kindly scolding from my wife’s best friend, it became clear we had come too far to stop now, whatever that meant.

Like the fourth day, the fifth was a bit of an uncomfortable blur. We were getting used to the choppy mixture of things and were also making our way out of the more urban areas and into the final stretch of suburban green that would take us to our close.

All of which leads to a fairly obvious point, but one I’ll make anyway because I couldn’t stop thinking about it as we walked through all of the various neighborhoods around 495, both inside and out: People use the phrase “inside the Beltway” to connote “Washington, DC,” and, essentially, all of the things the rest of the country hates about this city, with varying degrees of actual righteousness. But when you walk the Beltway, you realize (a) how far away from the actual city it is and (b) that in feel and feature, you’re actually a lot closer to the rest of the country than you are to what’s going on several miles closer to the core.

One of the things I was most looking forward to about the walk was the idea that I could get off of Twitter for a few days, that we’d be at a blessed remove from the constant, debilitating churn of events in Trumpland. But we hadn’t walked more than a couple of miles on our first day before news came of that morning’s shooting at a softball practice for congressional Republicans in Alexandria. There were some initial (incorrect) reports, texted by friends and family who knew we were walking in Virginia, that several lawmakers had been killed. A bit later, we stopped for our first water break at a Westin in Tysons, inside the Beltway near Marshall High School, and as we approached the dinky coffee shop/canteen in the lobby, the cable-news chyrons heralded a forthcoming statement by the President.

Mike sat down at a shared table in front of the TV, across from a guy in a business suit, and said something along the lines of “Oh, great, now Trump is going to come out and make it all about himself,” presuming he had a fellow traveler across the way. He did not. A pained smile and an awkward chuckle revealed that the man likely did not share many of Mike’s political views. Both Mike and I live in DC, which voted 90 percent for Hillary Clinton. This was the first, maybe clearest, example that spending time along the Beltway was going to be a lot different from being in the city itself. Which is what makes “inside the Beltway” a forgivable but ultimately odd shorthand.

In Virginia, “inside the Beltway” often meant vast tranches of suburbia that could just as easily have been outside Chicago or Philadelphia—or, for that matter, nestled in the heart of 1985. (Just to drive this home, we passed one development called Lions Gate, which looked almost identical to Lyon Estates in Back to the Future.)

In Maryland, there was a fair amount of sprawl but of a slightly less prosperous-seeming sort, particularly in Prince George’s County. At one point, we stopped to wait for a Good Humor truck to make its way out of an apartment complex near Joint Base Andrews, and when it rolled up, it was pretty dilapidated, its service window fortified with metal bars. The operator warily passed us our Toasted Almond and Creamy Coconut through a small opening, like a bank teller. Having grown up in upper Northwest DC, I was used to open windows and smiling faces. This was something quite different, probably the bleakest sight we saw.

When the last day finally came, with just a little more than ten miles to walk, from the Mormon temple down to Lock 12 on the C&O Canal, it’s hard to explain the relief we felt. By the time we walked under 495 on Seven Locks Road for our final crossing, we had already crossed the Beltway 18 times. The first time, we took pictures and got all jazzed up about it, but after nearly 89 miles we barely noticed anymore. It was just more steps. We had become expert at timing our street crossings to the nanosecond, pumping our arms faster as our feet shuffled along at the same slow pace, just to show the waiting motorists that at least we were trying.

What kind of idiots would hike the Beltway?

About a mile into that last leg, one of Mike’s colleagues at McKinley Tech High School in DC happened across us as she was out for a jog. “What kind of idiots would hike the Beltway?” she shouted from behind, startling us at first. Then she laughed and said, “Given how you were moving, it took me a minute to realize you weren’t two old men.”

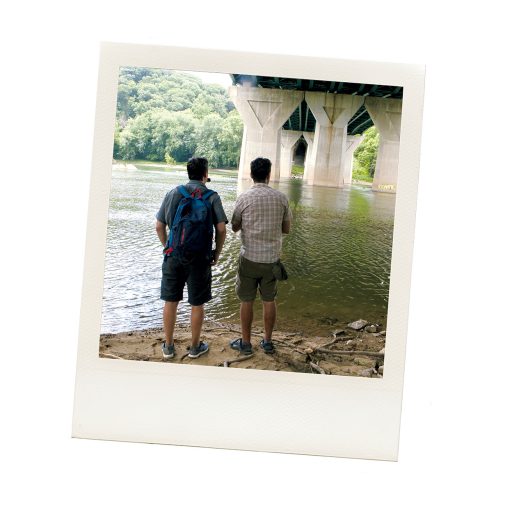

It was hot that final day, but we spent a lot of the time in the shade, through several well-maintained Bethesda neighborhoods and for a long stretch alongside Burning Tree Golf Club, which banned women members when it was founded in 1922, and still does. As we crossed River Road and then walked downhill from Seven Locks to Cabin John, we could feel the river approaching and the weight lifting as we closed in on the end. The last three quarters of a mile, from the Lock 12 entrance to the bridge that carries the Beltway over the Potomac, felt almost unreal. We turned onto a path similar to the one at Gibbons Roost and then made our way down to the riverbank under the bridge, looking back across the water to where we’d started.

There was no wonderful revelation to finishing, just relief. We had stopped on MacArthur Boulevard to buy some beers, so we sat on rocks by the water and drank them, joking about what going back to real life was going to be like. Only after it was over did we realize how much the task had taken over our lives for those six days. As my wife put it, even when I was home I hadn’t really been home. The project had taken on a life of its own, become a kind of quest for us, one we were willing to go to somewhat embarrassing lengths to complete. Then we were done.

So yes, we walked around the whole Beltway, and it was as punishing as you would probably imagine a walk around the Beltway would be. But there were also a couple of moments of sublime surprise, which is the whole point of doing it. One occurred as we approached a 495 crossing at the end of a residential street on the second day of the trip. Nearing the turnoff, we saw a man in a shirt and tie walking toward the outer loop, clearly on his way to work somewhere on the inside. But when we turned the corner ourselves, he had disappeared and all we saw in front of us was a wall. It was as if the neighborhood had ended mid-sentence. But the map said we should be able to cross, so we went closer.

When we got right up to it, we realized the wall was actually a couple of different walls with a path cut through them, a kind of baffle that would eventually spit us out on the other side. That guy ahead of us hadn’t magically disappeared into the Beltway; he had just known how to get inside of it, and so we followed him in.

Jeff Himmelman (@jeff_himmelman on Twitter) is a contributing writer at the New York Times Magazine and the author of “Yours in Truth,” a biography of former Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee.

This story appears in the September 2017 issue of Washingtonian.