Andrew Gifford slouched in the passenger seat, groggy and bewildered. His mother, Barbara, had rousted him from bed around 10 pm, made him change out of his pajamas, and dragged him to their station wagon. The sky was black, the spring air cool and fragrant with azaleas. The car reeked of his mom’s Newports.

“Where are we going?” Andrew asked.

She shushed him.

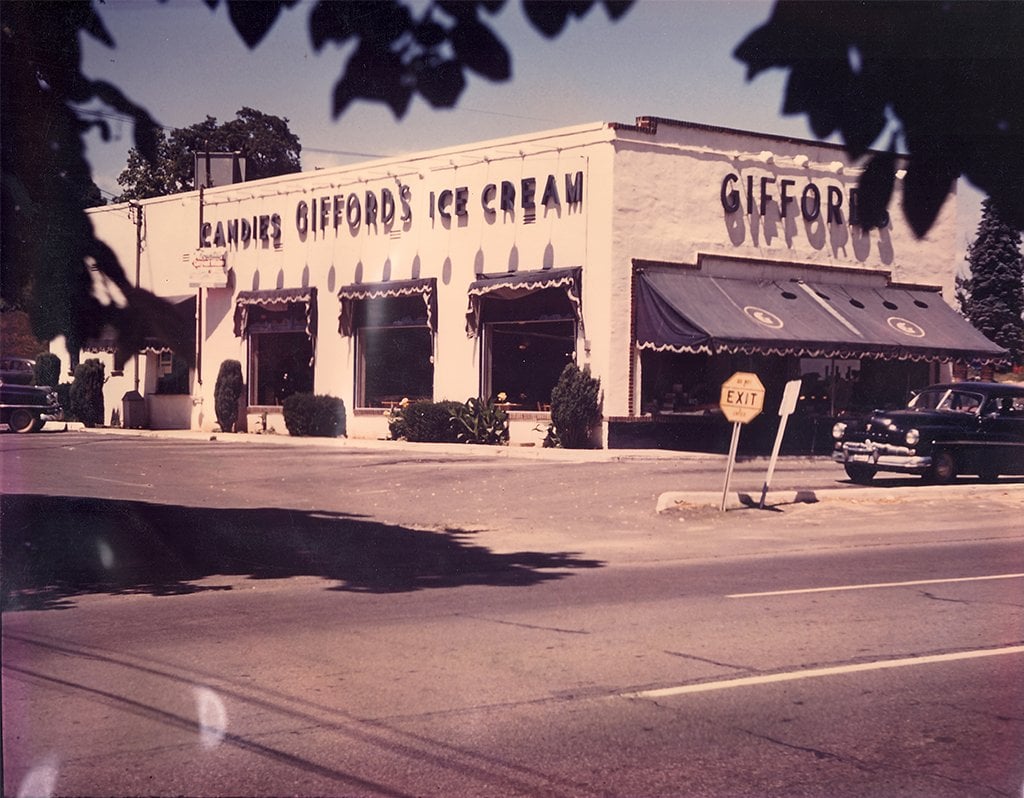

Barbara sometimes called her son “the prince of ice cream,” and in the Washington suburbs of 1985, there was some truth to that. Andrew’s paternal grandfather was John Nash Gifford, who launched Gifford’s, an extremely popular chain of ice-cream parlors, just before World War II. Its fans included, per company legend, Jackie Kennedy, Mamie Eisenhower, and J. Edgar Hoover. But more important were the generations of everyday Washingtonians for whom the shop was an indelible touchstone: a vanilla respite from swampy summers, a chocolatey reward for a good grade, a strawberry balm for a Little League loss.

The prince of ice cream, an only child, had grown up steeped in Gifford’s lore. Light-haired, with a big say-cheese smile, Andrew had learned to read, in part, from the blue-and-white menus offering a regular sundae for 95 cents and a jumbo for $1.15. He spent his childhood roaming the grounds of the Silver Spring headquarters—the plant that churned out Swiss Chocolate, Peppermint Stick, and other velvety flavors, the hundred-seat parlor where chandeliers dangled above waitresses flitting from worn Formica table to worn Formica table, heels scuffing the red-and-white checkered floor.

Andrew thought that was where his mother was headed in the station wagon that night—May 10, 1985, his 11th birthday. Instead, Barbara parked the car, inexplicably, outside Jhoon Rhee Tae Kwon Do in Kensington. She glanced in the rearview mirror, snuffed her cigarette: “Okay, let’s go.”

Andrew climbed out of the station wagon and walked toward a man in a blue-and-yellow baseball cap, white karate garb, and a brown belt—his dad. It had been a while since they’d seen each other.

Bob Gifford, a graduate of Landon and Harvard, had been the guardian of the family legacy for years, running the company after his parents died. But just a few weeks before, Gifford’s had shut down. The closure was huge news around town. The business was in bankruptcy and about $350,000 in debt, a company attorney told reporters. Bob, according to the news, was missing. There were whispers he’d vanished with millions of dollars.

Andrew was a curious kid, head always burrowed in a book, but he was too young to realize that the ice-cream dynasty had dissolved. All he knew was that it was the middle of the night and his father was kneeling before him on the pavement. “I’m going on a little trip to Charlottesville,” Bob told him. “I’ll be back next Monday. Do you understand?” Andrew nodded. Bob faded into the dark.

He didn’t come back the next Monday. He never came back.

The end of Gifford’s baffled Washington. Perhaps that’s one reason why nostalgia for the original has lingered for the last three decades. The name still conjures so much wistfulness that, since the bankruptcy, entrepreneur after entrepreneur has paid for the rights to it.

“I didn’t think to call it Dolly’s,” says Dolly Hunt, who revived Gifford’s in 1989 and ran it for about a decade. Several iterations later, in 2011, a Maine company named Gifford’s bought the Maryland Gifford’s name. Two years ago, a local anesthesiologist named Mark Schutz hired a private investigator to track down Hunt—he wanted to sell authentic Gifford’s ice cream in his family’s chocolate shop in Friendship Heights, even if he couldn’t advertise it as Gifford’s.

But for Andrew Gifford, there was never any such nostalgia. The Gifford’s worship tormented him. After hearing about Hunt’s revival when he was in high school, he ran off the Bethesda–Chevy Chase campus, choking back tears. When he was older, he says, the specter of Gifford’s trailed him to grocery stores and restaurants. He pulled out his credit card and someone would ask, “That Gifford’s?” Each instance was a pinprick. These weren’t just reminders of his father’s disappearance or that strangers were cashing in on his name.

“It is hard to have people say, ‘We owe a great debt to your father and your grandfather,’ ” Andrew says. “They’re treated like saints—ice-cream saints.”

If people were going to venerate his family, he decided, they should know who his family really was.

Earlier this year, Andrew published a tell-all, We All Scream: The Fall of the Gifford’s Ice Cream Empire, roiling some members of the Gifford clan and sullying the wholesome memories of their family name with revelations that wouldn’t feel out of place on a daytime soap. Abuse. Fraud. Deception. Ghosts.

“For the first time, I’m telling everything. Every secret I was sworn to keep, on pain of death, when I was a child,” he told Delphi Quarterly, an online journal. “The closure I seek is to take the power away from all of these secrets. I’ll give them to the public, and they will no longer be my secrets.”

If memoir is a genre that taps into our desire for linear clarity, Andrew’s sprang from a much deeper and darker well. Just as Bob Gifford destroyed his father’s company—the brick-and-mortar family inheritance—Andrew’s book is its own act of sabotage.

One day earlier this year, Andrew and I parked in front of the Kensington house where he grew up. So little had changed that he might as well have been staring at a Polaroid from 1985. West Bexhill Drive: stately homes, majestic foliage, prim lawns. His old house: two stories, white with blue trim, big picture windows. Andrew is 43, with graying hair, facial scruff, and oval glasses. He looked stricken. He’d been here earlier in the year with a columnist for the Georgetown Dish website, who asked him to stand in the yard so she could snap a photo.

“I felt like the house was reaching at me, like a Stephen King thing. It was weird,” he told me. “I kept expecting to turn around and Mom to come out the door or something.”

Barbara had met Bob when she started waitressing at the Silver Spring Gifford’s after high school. He was 15 years her senior, with an, er, reputation among the staff. By the end of 1973, she was pregnant and they were shotgun-married. In photos, you could easily mistake Barbara for a Breck girl: A cascade of thick black hair frames a freshly scrubbed face and easy smile. Her effervescence masked a host of demons.

‘I’m going on a little trip to Charlottesville,’ Bob Gifford told his son. ‘I’ll be back next Monday.’ He never came back.

Andrew writes that his mother spent much of his childhood gaslighting him. When she heard about the Gifford’s in Maine (the people who later bought the Maryland Gifford’s name), she warned her son, “Next they’ll steal our skin.” Literally. She called them “usurpers” and “skinwalkers,” and she vowed that Bob would hire goons to wipe them out. Later, Andrew says, she had him break apart thermometers so that, she said, the mercury and glass shards could be dumped into the ice-cream base mix at the Silver Spring plant. Andrew was so repulsed that, even now, if he eats ice cream, he panics: “Am I eating crushed-up glass?”

“My sister would pretty easily hit the mark for an antisocial personality disorder,” Barbara’s older brother, Richard Currey, says. Their parents had taken Barbara to a psychiatrist when she was five or six, an unusual move in the 1950s. “Within just a few minutes, my sister stood up and spat on the doctor and then ran out of the room,” Currey says. A few years later, Andrew writes, Barbara dangled her younger sister off a railroad bridge, threatened to drop her, and laughed.

Bob Gifford was as ordinary-looking as Barbara was striking—a spindly man with receding brown hair and thin sideburns. His ears stuck out a little, and he wore large, round glasses. At holiday dinners, he was only slightly more animated than a piece of furniture. “He would startle when directly addressed,” Currey says, “as if he was amazed to discover there were other people at the table.”

Bob was a tortured soul. Not long after he took over Gifford’s in 1980—he had no siblings to join the family business—he started stiffing vendors and suppliers and fired the entire administrative staff.

“There’s still coats hanging up. There’s still coffee cups—it’s as if they evaporated,” Andrew says, remembering his visits to the headquarters. “It’s exactly a horror movie.”

His father’s office smelled of cigarettes and sour milk, he writes, and Bob would remove whiskey from his leather briefcase, sink into the coats his dead father had left in the closet, guzzle straight from the bottle. In the bowels of the building, rat carcasses decayed in traps, and so many cockroaches skirred across the floor that, Andrew writes, the waitresses called their pointy-toed shoes “roach-killers.”

Bob and Barbara warred over just about everything. During one brawl, she hurled a stool into the wall and Andrew into a bookcase, he writes. He escaped into reading and TV, particularly science fiction, and fantasized that Commander Adama from Battlestar Galactica was actually his dad. Around Christmas 1983, Bob decamped to Gifford’s headquarters. “When I asked if he was coming home, Mom would shrug or tell me, ‘I don’t know,’ ” Andrew writes.

Bob was running away from more than his wife and child. Later, an employee told Andrew that, as Gifford’s spiraled toward bankruptcy, part of her job was to warn Bob if anyone came to the plant looking for him.

It wasn’t exactly the domestic life patrons might have imagined. Through the decades, Gifford’s advertising campaigns evoked Leave It to Beaver wholesomeness (“Made with family pride . . . to serve with pride to your family”). Even the menu of Andrew’s youth suggested multigenerational harmony (“Gifford’s stands by its family traditions”). The 62-word history on the menu, though, was pretty much all Andrew knew about his paternal grandparents—Bob barely spoke their names. Both had died when Andrew was young, and Bob had his mother buried in an unmarked grave. He wasn’t the type to explain why. “Gifford men don’t talk much,” Bob’s cousin Nash Gifford says.

Barbara offered her own explanation—a salacious set of allegations that, in addition to the menu, formed young Andrew’s understanding of his grandparents. He shares it in the book’s first chapter.

“By the time I was six,” he writes, “I had a clear and intimate idea of what rape and sexual abuse were like, thanks to my mother’s natural ability to tell a story, weaving a complicated narrative while occasionally acting out key scenes.” According to Barbara, the perpetrators were either Bob’s father, John, or his mother, Mary, and while Barbara often invented stories, on this point she never wavered.

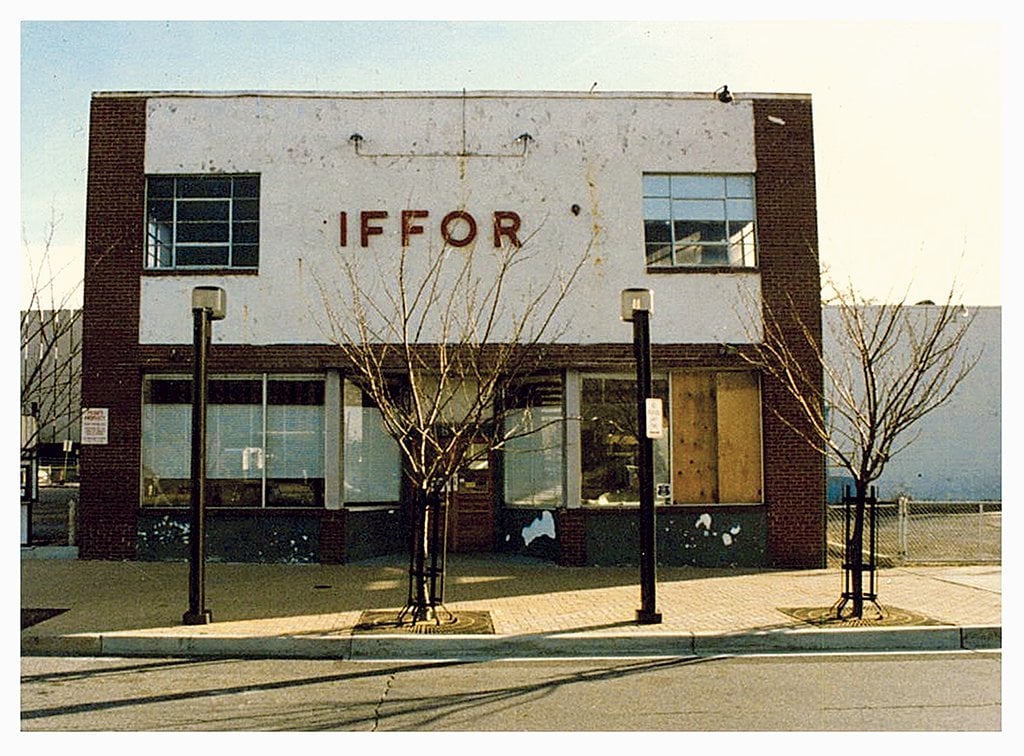

Andrew finally learned about the demise of Gifford’s not from his parents but from the evening news. In one clip he still has, a reporter stands in front of the Silver Spring headquarters, which, with two blocky black letters missing, advertises giffor ’. At the behest of a bankruptcy judge, the reporter says, the sheriff shut the business down. Then a former employee speculates as to why Bob vanished: “I think it was the pressure. He had so much pressure. He just couldn’t handle it.”

Andrew didn’t know much more, and no one offered to tell him. The news coverage drove looky-loos to peer into the family’s windows and mail slot. For a couple of weeks, Barbara closed the curtains, unplugged the phone, kept Andrew out of school. Once the publicity subsided, she further unraveled. She told a reporter that Bob had drained their bank accounts, forcing her onto welfare until she found a job.

“Whether she loved him deeply or not, that was abandonment,” Kelly McEntee, who dated Barbara years later, told a filmmaker for a documentary that was never made. “And being abandoned is being abandoned. There’s nothing there. You’re on your own.”

Barbara downed Coors, swallowed pills, chain-smoked so furiously that she stained the walls. Her religiosity bordered on insanity. She stopped cleaning—letting a backed-up toilet stink up the entire second floor—until, she said, Saint Francis told her to spiff up the house for an archbishop’s visit. She also believed she’d spoken to a bird that was really Jesus Christ reborn. She lashed out at Andrew, too.

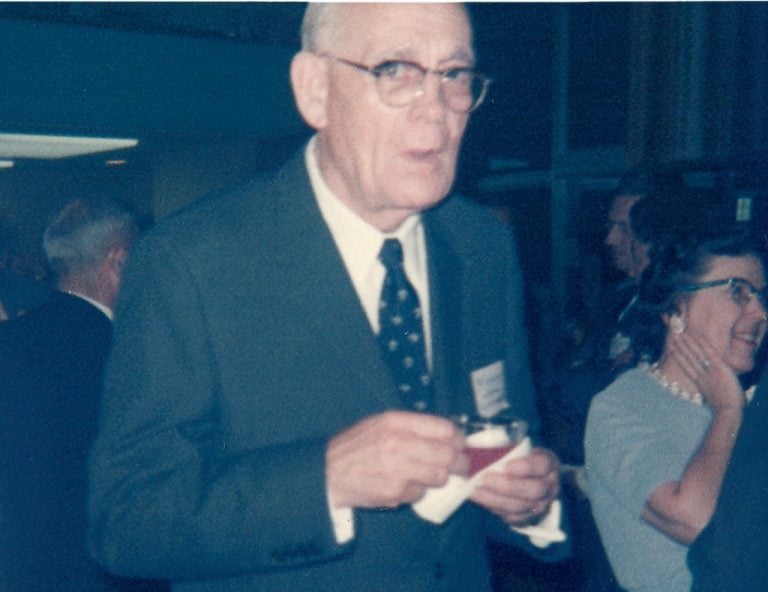

Andrew's parents, Barbara and Bob. Bob, who ran the chain for years, vanished in 1985. Photograph courtesy of Andrew Gifford.

Andrew's parents, Barbara and Bob. Bob, who ran the chain for years, vanished in 1985. Photograph courtesy of Andrew Gifford. Andrew's grandfather John Nash Gifford founded the business. After his death, Bob took over. Photograph courtesy of Andrew Gifford.

Andrew's grandfather John Nash Gifford founded the business. After his death, Bob took over. Photograph courtesy of Andrew Gifford.“Most of her rants ended with the accusation that I was in cahoots with my father and that we were both plotting against her,” he writes. “I looked so much like him, she said, that it was impossible we weren’t the same person, here to destroy her.” Teenage Andrew retreated into himself, scribbling “little diaries full of hatred and anger,” as he called them—the seedlings of a memoir he christened “Ice Cream Dreams.”

Once Andrew graduated from high school, he mostly cut ties with Barbara, though in a way she shadowed him everywhere. On a trip to England before finishing college, he glimpsed a willowy, dark-haired woman on a trail. Could it be . . . ?Just in case, he ran off. Then in the summer of 1999, when Andrew was 25, Barbara veered off a road near Shenandoah National Park in Virginia. Her car slammed into a tree. Flames. Her death was ruled an accident, but Andrew believes she killed herself. In his book, he describes her place in Frederick as an “efficient suicide note”: house scrubbed, bills paid, passwords jotted down.

Barbara also felt like too potent a force to have died by anything other than her own hand—I heard Andrew joke repeatedly that she may have faked her own death. “At every [book] reading, I expect her to come out from behind a pillar or rise up in the back of the audience or something,” he told me when we were parked in front of his childhood home. “I wouldn’t be surprised. Rationally, realistically, I know she’s dead. But if she were to step out from behind that tree, I’d be like, ‘See—told you.’ ”

Eventually, a woman’s voice interrupted our conversation: “Can I help you?” She was calling from a window on the second floor of the West Bexhill Drive house. It was likely the current occupant, and we could have easily explained why we were there. Instead, Andrew drove off.

Barbara’s death should have allowed her son to let go of his childhood anguish. But another ghost reappeared: his father.

In the roughly 15 years since Bob’s vanishing, Andrew had come to believe he was dead. In reality, his father was living in Atlanta. Andrew didn’t learn this from a phone call, an e-mail, or a stilted hello. He found out from his attorney. Barbara’s modest estate was being divvied up in court, and Bob wanted a piece. He and Barbara had never divorced.

Andrew felt as dazed as he had that 1985 night in the Jhoon Rhee parking lot. Then he got angry. Very angry. “What do you do for 15 years if you walk away from your family and your business and destroy all these things?” he asks me. “What’s in your head for that 15 years? What do you tell yourself? How do you wake up with that, you know?”

Andrew never spoke to his dad during the case—only their lawyers talked. Two years later, Bob, out of nowhere, started begging him to move to Georgia.

People assumed Gifford’s collapsed because Bob, despite his Harvard pedigree, was a lousy businessman. Andrew came to a bleaker conclusion.

“Every letter ended with the same theme—he had emphysema, he didn’t have long to live, he needed me to help him,” Andrew writes. “He was asking me to not only be his live-in nurse but also help pay his bills. In what world did that make sense?” Andrew responded by asking about the money Bob had allegedly swindled. “He avoided my question and instead made a demand that I send my mother’s collection of vinyl records down to him.” Andrew refused.

He never found out much about his dad’s time in Georgia—you could probably fit Bob’s paper trail into a single manila folder. He worked as an accountant. His clients apparently paid cash. He bought a ranch house so sparsely furnished that Andrew compared it to a “poorly stocked safe house,” though for some reason Bob hung onto the brown leather briefcase from his Gifford’s days.

His social life appeared just as scant. In e-mails to his cousin Nash, Bob said he’d dated some, even tried Match.com, but nothing panned out. He wondered if his marriage to Barbara had scarred him. “I remember being fearful of falling asleep in the same room with her, lest she stab me with a kitchen knife while I was sleeping,” Bob wrote to Nash. He didn’t mention skipping town—just that “Andrew thought I had horns and was the devil incarnate.”

By 2005, Bob’s emphysema was so bad that he was hooked to an oxygen tank. Even so, he could barely wheeze out a sentence. Andrew relented and flew down. He wanted to confront his dad—and frankly, if Bob had stolen millions, Andrew felt he was owed some of it. Though he was working in customer service at the American Psychological Association, he’d started his own publishing company on the side and was subsisting on ramen and debt to keep it afloat.

“Why’d you leave?” he says he asked his father.

“It was the best thing to do for you.”

“How was it good for me? How can you say that?”

“I had to stop the fighting. You needed peace. I gave you peace.”

Far from it, Andrew thought. Mom and I were broke, he told his father. He’d scrimped his way through college with part-time jobs, student loans, maxed-out credit cards.

His father’s response floored him: “You shouldn’t have had to worry. I sent all the money.”

In April 2007, Andrew was wheeled into surgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore to, he hoped, fix once and for all a condition that had plagued him even before his mother’s death.

For years, he’d experienced inexplicable and excruciating pain in his face. It could be triggered by a toothbrush massaging his gums, water splashing his forehead, a pillow grazing his cheek—any sensation could be a lightning bolt. It’s why, though he sometimes thought of changing his last name or fleeing town to escape the Gifford’s shadow, he never did. I’m going to be dead tomorrow, he thought, so why bother?

Andrew visited doctor after doctor in search of a diagnosis. He swallowed so many painkillers, and at such high doses, that he sometimes forgot which Metro stop was his. “I even became obsessed with the idea that the pain was my only companion—the only one I deserved,” he writes. “I called it my ‘wife.’ ” More than once, he considered killing himself.

Then he was referred to Ben Carson. Yes, that Ben Carson—at the time, Hopkins’s director of pediatric neurosurgery. Carson also operated on patients with trigeminal neuralgia, a condition so remorseless that it’s nicknamed the suicide disease. In people who suffer from it, the nerve between the brain and the face becomes compressed by a blood vessel. During the surgery, Carson separated Andrew’s trigeminal nerve from the blood vessel compressing it, wrapping a piece of muscle from his neck around the nerve to prevent further damage. When Andrew came to, a physician’s assistant pinched his cheek. It didn’t hurt. It didn’t hurt.

“He thought all his problems would be solved,” his friend Rose Solari says. “And he woke up and realized that the burden of his family was still on him.”

Bob had died a few months before the surgery. Andrew had come no closer to learning why his father had sabotaged the family business or what had happened to the Gifford’s fortune—where the money Bob said he’d sent to Barbara had gone. It had been easier to bury those hard questions than to confront them.

Ever since his early “Ice Cream Dreams” screeds, Andrew had been toying with writing a real memoir. With his pain now vanquished, his relationship with his first serious girlfriend flourishing, and his publishing company, the Santa Fe Writers Project, starting to take shape, he felt emotionally steady enough to try. In 2013, when he was 39, Andrew shared his plan on Facebook:

I think the deciding factor is the fact that Gifford’s is very painful for me. . . . It destroyed my family, it drove my mom to suicide, and it haunts me every day. Which wouldn’t be so bad if it wasn’t constantly coming up.

As he plumbed his memories, he posted updates—mostly humorous, if grim:

Oh, I see the problem with the Gifford’s memoir. Everybody’s going to expect a Willy Wonka story when, in fact, it’s more like a bad night in the kitchens at the hotel from The Shining.

Indeed, Andrew was so terrified to dig through his mother’s belongings that he’d locked them in storage for years. At his girlfriend’s prodding, he tossed all but four boxes’ worth of Gifford’s employee instructions (“Clean, sparkling glassware magnetically attracts business!”), age-mottled recipe cards, crayon drawings, and baby teeth. I went through them one afternoon at his townhouse in Bethesda. When I finished, Andrew immediately shoved them back into a closet, as if they amounted to a Ouija board that would conjure Barbara’s spirit.

Over a few years, he did more sleuthing—tracking down company incorporation papers, chatting up relatives and old employees. He launched a Gifford’s Facebook page, a tacit admission that, perhaps, the internet knew more about his parents than he did.

I was haunted by nightmares, I spent long days simply exhausted and depressed, and I’m still struggling with the edits to honestly speak about everything that happened.

Andrew is an author, not a detective. Even if he were, much of the Gifford’s saga is tough to pin down. Public records, including the bankruptcy file, have been destroyed, and most key players are dead. When he doesn’t have a definitive answer for something, he often takes a leap. That’s what we do to make sense of trauma: tell ourselves stories, real and imagined.

The story he ultimately pieces together is tragic. For one thing, Andrew didn’t realize his dad was a lecher who harassed the waitresses at the Silver Spring Gifford’s. He says he talked to six of them and was too disgusted to look for more—he began to suspect Bob had preyed upon the much younger Barbara as opposed to wooing her.

As he rifled through his mother’s boxes, Andrew’s vision of his parents darkened. Letters and court records confirmed that, for much of his teens and twenties—while he was convinced his father was dead—Barbara knew exactly where Bob was. A few years after he skipped town, they were locked in a court battle in Georgia, with Barbara saying Bob had saddled her with thousands of dollars in debt.

Andrew crumpled. Here was concrete proof that much of his childhood had been based on a lie.

Perhaps most perplexing was the fate of the Gifford’s fortune. Andrew recounts how after Bob’s death, a family friend—Andrew calls him “Peter”—came forward and told him that Barbara did receive money from his father: about $5,000 every month. Peter claimed it was his job to oversee the funds, check in on Andrew weekly, and report back to Bob. He said he’d leave the cash for Barbara via spy-style dead drops, the kind of scheme you’d see in a Cold War thriller.

“Seemingly ludicrous and impossible,” Andrew writes, “but then I had found letters from Dad to Mom that alluded to such a scenario. . . . In one letter to Mom from Dad in 1989, he wrote ‘4/15—$3200—at the usual place in Silver Spring.’ ”

If the story is true, Andrew wonders in the book, where did all the money go? Drugs? Friends? When they died, Barbara and Bob had little to show for it. Andrew asked Peter. “Both of your parents were very sick,” he replied, according to Andrew. “You understand that, don’t you?”

A friend revealed he’d been helping Bob send $5,000 a month to Andrew’s mom. He said he left her the cash via spy-style dead drops.

Many people assumed that Gifford’s collapsed because Bob, despite his Harvard pedigree, was a flop as a businessman. Andrew reached a much bleaker conclusion. He thinks his father stole from the company and potential franchisees—if not millions, then close, because he survived in the shadows for so many years. His motive, Andrew believes, lies in the stories Barbara told him as a boy: that Bob’s parents, Washington ice-cream royalty, had severely abused him.

It’s the kind of allegation that can tear a family apart, but in the case of the Giffords, there aren’t many relatives left to defend Bob or his parents. Bob was an only child, but as a boy he spent time with his cousin Nash. Their fathers had a falling-out, but Bob and Nash reconnected just before Bob died. Nash is skeptical of some of Andrew’s childhood tales. “He was only 10 or 11 when some of these horrible things supposedly happened,” Nash says. “Not that that ruins your memory, but it can become distorted, and you have to factor that in, too.”

As for Andrew’s speculation about Bob—the childhood abuse, the adult con-artistry —Nash has serious misgivings, and Andrew allows that he doesn’t have incontrovertible proof.

“A lot of it is conjecture,” Andrew says. “When you put all those things together, with the wild, probably mostly fictional stories, there’s something there, something happened. Who knows what?”

It would, however, explain why Bob distanced himself from his parents, why he couldn’t connect to anyone emotionally, and why he bankrupted Gifford’s: as revenge.

“He could not kill the people who had abused him,” Andrew writes, “so he aimed to kill their legacy instead.”

One overcast afternoon, I joined Andrew at a book festival down the street from his childhood home. He stood at a folding table in a long line of folding tables, rocking from foot to foot—he didn’t quite know what to do with his hands. His table, number 4, was covered with a light-blue sheet, which had faded to white in spots, and groaned under about a dozen copies of his memoir. Person after person overlooked We All Scream’s dark-hued cover and campy title. They shrieked, “Gifford’s!”

The “nostalgia people”—Andrew’s words—don’t bother him so much anymore. Piecing together his version of the family history was in itself a form of therapy. “I wouldn’t have done this if no one had mentioned Gifford’s,” Andrew told me later. “If this had all died and gone away and here we are, 30 years later, and nobody’s talking about it and nobody’s trying to reboot it and the name’s never come up and everyone’s dead who remembers, or they don’t care because it was ages ago and there’s been hundreds of amazing ice-cream places since—if that were the reality, I wouldn’t have written this book.”

Instead, at the festival, a woman cradling a small dog and a red rose walked up and asked Andrew, “Are you part of the family?”

“I’m the last one,” he said.

“What’s going on now, anything? Do you have any locations?”

“Oh, no, no—it all fell apart in ’85,” he replied.

Andrew accepts that he can’t erase the past. Can’t even completely explain it. In the absence of undisputed truth or a family fortune, there’s only one thing to reclaim from the ashes of his family: his name. Later that day, he sat on a small tented stage, fielding questions from a few dozen people. Outside, parents wheeled strollers, kids shriek-laughed.

“We have a question in the back,” the emcee said. “Yes, ma’am.”

“When are you going to reopen?” a woman shouted. “When are you going to come back?”

“Read the book first,” Andrew replied, “and then that will answer your question.”

Laughter.

The woman persisted: “We miss you. We miss Gifford’s a lot!”

Andrew forced a smile and moved on.

This article appears in the October 2017 issue of Washingtonian.