The voice on the phone seemed a little too chipper. Tom Sietsema wondered if he’d been made. Or was he being paranoid? Maybe Le Diplomate’s reservationist was always this enthusiastic about hosting a party of eight at the buzzy French restaurant. Either way, as usual, the Washington Post’s lead restaurant critic made his reservation under an alias. This time, it was Dean Cook.

Of course, no mere fake name was enough to fool a top competitor in DC’s dining scene. Back in the manager’s office was a sign listing all of Sietsema’s known aliases and every phone number and e-mail address he’d ever used to make a reservation. If the reservationist were to miss him, a manager checked the books daily. Starr Restaurants’ corporate office in Philadelphia also screened the reservation system. Sietsema’s photo, along with those of dozens of other food writers and editors, was posted in the kitchen.

The Dean Cook reservation was for Super Bowl Sunday 2016—ordinarily a slower night. Not this time. Behind the scenes, Le Diplomate was preparing for its own game day, according to accounts from three staffers. (Like many of the restaurant insiders in this story, they requested anonymity.) The restaurant, known for its fashionable clientele, had been knocked from three stars to two and a half in the Post’s last review, and the team was eager to earn its rating back.

As the evening approached, the staff ran through its critic checklist—a document employed with extra attention to detail during spring and fall “critic season.” They inspected the light bulbs. They searched for gum under tables. One manager showed up a few hours early to gather brand-new, never-used silverware, glasses, and plates from a stash stored in the church next door. The dinnerware was washed, polished, and set aside specifically for Sietsema’s party so he would see no scuff marks or chips.

Meanwhile, the team strategized about just where in the 260-seat dining room Sietsema should be seated. They didn’t want him to see too much of their maneuvering and staring. They also didn’t want him too close to the noisy bar. Table 51, a banquette in the “salon” section, seemed best.

At 6 pm, it was showtime. As Sietsema and his friends trickled in, a manager made the rounds to alert staff, quietly repeating: “Tom’s here.” Someone scrawled Sietsema’s name on the kitchen whiteboard that tracks everyone in the dining room designated “PPX,” the French code for VIP, meaning personne particulièrement extraordinaire.

The chefs made two of everything. The nicer-looking plate was sent out to Sietsema. Senior staff sampled the duplicate to reassure themselves.

Unfortunately for the restaurant, Sietsema wasn’t there for a review. It was his partner’s birthday, and his partner had picked the restaurant. For once, Sietsema wouldn’t need to instruct dining companions on what to order, or sample everyone’s dishes, or otherwise do the work of a professional eater.

Still, the restaurant was busy masterminding a culinary version of The Truman Show. At one point, Sietsema noticed a table to his right filled by a smartly dressed couple having the best time of their lives. Hundreds of meals later, Sietsema still remembers how the blond woman kept looking over and smiling. Le Diplomate had purposely seated regulars who it knew would be having a good time within the critic’s vicinity.

Managers were equally intentional about who took Sietsema’s order, ran his food to the table, and bussed the dishes. The best server—a charming Moroccan guy who trained other staff and was known for being extremely knowledgeable and polished—saw to Sietsema’s group and maybe one other table. Actual servers with food-running experience took over for the regular runners and bussers. Sietsema noted a lot of suits stopping by.

The bar staff was also sweating the details. When the group started with a round of cocktails, the bar manager made duplicates of each and sent out the prettier versions. The wine director personally poured a bottle of Domaine Cros Minervois Vieilles Vignes 2000.

Back in the kitchen, chefs prepared two foie gras parfaits, two steak frites—two of everything Sietsema’s table ordered. The nicer-looking plate was sent out, while at least four senior staff sampled the duplicate to reassure themselves that nothing tasted amiss. A manager and the executive chef also photographed each dish, then texted the images to corporate honchos in Philadelphia.

When the main meal was over, the same routine transpired: The chef and a manager lined up the dirty plates on a prep table and snapped pictures again, looking for hints about what the critic and his friends had or had not liked.

At dessert, a cake lit with a candle emerged. Not just any cake. The pastry chef had specially prepared a gâteau St.-Honoré, a classic French dessert made of pâte à choux and pastry cream. The cake isn’t on the menu, though anyone in the know can request one with advance notice. Typically, it’s made only for regulars celebrating special occasions or for VIPs. Chances are slim that it would be made on a whim for some guy named Dean Cook.

Plenty of attention has been paid to the zany things major restaurant critics do to preserve their anonymity in top dining rooms. But there’s less awareness of the epic countermeasures from the eateries themselves. For Le Diplomate and restaurants like it, these machinations aren’t just games. They’re about business and reputation and morale.

“You’re terrified of these reviews sometimes,” says a former Le Diplomate employee. “They’re make-or-break.”

Sure, the impact of individual critics—particularly the lead reviewer for any city’s newspaper of record—has been diluted by blogs, Yelp, and a food-obsessed culture in which everyone has a savvy friend to turn to for recommendations. But none of that has changed much about the way so many restaurants feel about the power and danger of a good old-fashioned review. As much as they publicly tout treating every guest the same, plenty of places will go to great lengths to identify and manipulate critics. Anything for those stars.

A vast and complex Underworld is devoted to identifying and understanding critics. Some of it is pretty obvious. You’ll find photos of food writers plastered in restaurant kitchens or embedded in staff training manuals. Many restaurants go further, applying CIA-level tactics to tracking personal information and preferences of the people who might write about them. One dossier—or “critic bible”—I reported on a few years ago noted that Sietsema “tends to get wrapped up in his conversations,” among other observations about the local food-writer set.

The handbook went on to list likes, dislikes, and which type of server would be best matched to which writer (“most personable,” “engaging but hands off”). It rated each journalist’s writing skill and food-and-beverage knowledge.

The dossier’s creator, it turned out, came from politics—he considered the information to be opposition research of sorts. “When you’re in a field where somebody’s there to criticize you,” he told me, “you need as much information about that person as you can get to understand their position.”

In fact, many restaurants know food writers’ aliases, significant others, and friends. They know what days of the week and what times they typically like to dine. Some closely track preferred dishes, wines, servers, and sections of the dining room. One of the most extensive dossiers I’ve seen, used by a major Washington restaurant group, went so far as to list alcohol tolerance. (My own bio: “3 drinks until tipsy”—generous!)

Restaurants may be competitive, but a fair amount of this information circulates among them. One sommelier says that a critic guide with photos and a few sparse notes was shared several years ago among members of the Neighborhood Restaurant Group (which owns Iron Gate and Birch & Barley), ThinkFoodGroup (of Jaleo and Minibar fame), and Mike Isabella Concepts (he’s the impresario behind Kapnos and Graffiato). “They update them and add to them,” he says. “Everyone gets a core one, and then there’s 2.0, 3.0, 4.0. It’s like smartphone updates.”

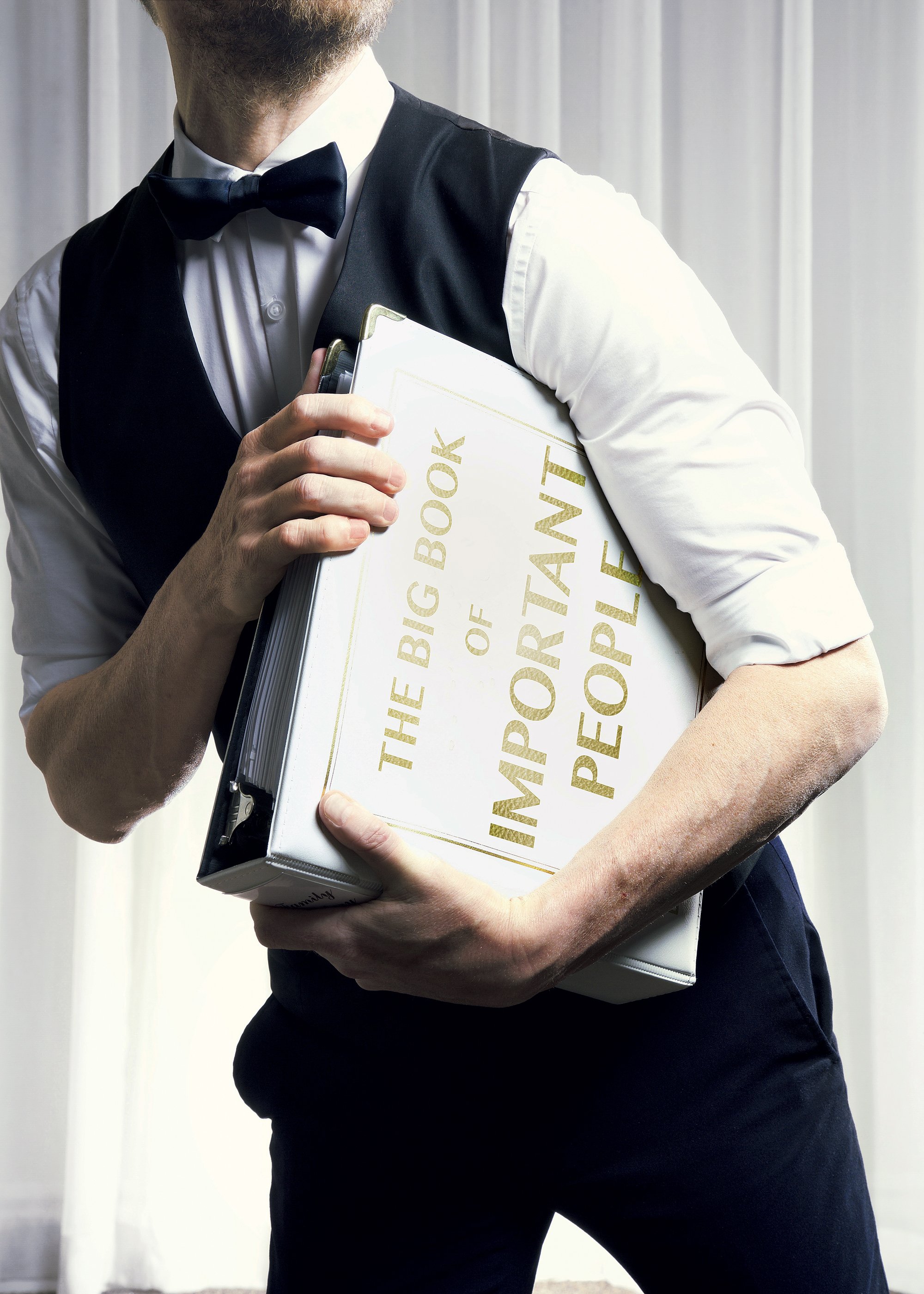

Meanwhile, one fine-dining restaurateur who keeps a photo album literally labeled the big book of really important people has an arrangement with a colleague at one of DC’s very best restaurants to share critic aliases.

“I feel like I’m going to break some hearts, but there’s no anonymous critic in this city,” says another industry veteran. “Everybody knows exactly who you are. It’s a fun game we play. I get texts from friends working at other restaurants asking, ‘Hey, I think [Washingtonian critic] Ann Limpert may be sitting in the restaurant. Do you have a photo?’ And I’ll shoot a photo over.”

As a result, a lot of restaurants have identical photos of Washington’s “anonymous” critics. One Sietsema shot in particular occupies professional kitchens like chalkboards in classrooms: He appears to be in a winery—there’s a barrel behind him—and he’s looking down and to the side, unaware of the photographer. Unlike in other photos of him I’ve seen floating around (where he’s wearing a straw hat and pink lei or a cap and sunglasses), his face is unobstructed. You’ll find the picture at Le Diplomateplus Neighborhood Restaurant Group and ThinkFoodGroup establishments, to name a few. No one I spoke to knows exactly where it came from—not even Sietsema himself when I showed it to him. He guesses it was taken five or six years ago—maybe in California? Or Virginia? Either way, he doesn’t have that blue shirt anymore.

Not that eager restaurateurs aren’t trying to improve on the dated intel. Sietsema has caught people trying to sneak snapshots of him in restaurants. At now-closed Gypsy Soul in Fairfax, Sietsema encountered one of chef RJ Cooper’s eight-year-old twins. “My mommy’s been taking pictures of you!” the girl squealed. Other restaurants mine their security footage and print screen shots. One longtime manager offered $100 cash to staff who could spot Sietsema.

For a while, my colleague Ann Limpert’s portrait was a little harder to come by. A former manager at an upscale small-plates spot had a photo of a young Joan Didion who “supposedly looks a lot like her.” Alas, Ann wasn’t safe from a covert snapshot at a Washingtonian event. A source says that photo got into one of the critic guides and eventually made the rounds. “You’ll just be like, ‘Hey, want to show me your packet? I just got this picture in my packet.’ You do a little resource trading. That can happen on a general-manager level or a corporate level.”

But the photos—often tiny and low-resolution—help only so much. What’s more valuable is having someone who has interacted with food writers face to face and can ID them without the grainy images. One bartender says that being able to spot people helped get him hired at a now Michelin-starred restaurant. Brent Kroll, who owns the Shaw wine bar Maxwell Park, says that years ago, he saw a manager fired in large part because he repeatedly failed to spot critics.

Another upscale restaurant got a pretty good review in the Post, but it was clear that a lot of the observations, including complaints about the meal’s pacing, came from a dinner the team didn’t know about. Owen Thomson, a longtime bar manager for many of DC’s top restaurants who now co-owns the U Street tiki bar Archipelago, says the owner of the place went back through security footage to find Sietsema’s visit and prove no one had seen him, then gathered managers in the office and yelled for about 20 minutes: How could a critic possibly sit through a whole meal without anybody noticing? Were managers actually on the floor as they were supposed to be? The staff tried to defend themselves here and there, but the mood was somber.

“With all these pictures, everyone knows who everyone is, so when your boss finds out that so-and-so dined at the restaurant and nobody noticed, it’s like a cardinal sin,” Thomson says. “If your job is to watch the restaurant and you missed that, what else do you not see?”

Once the critic is spotted, the machinery kicks into gear. Ideally, the news quietly ping-pongs from the host stand to the manager to the kitchen to the bar. If key staff aren’t there, they’re called in.

“Kliman’s here. All hands on deck,” a former employee at the downtown Italian restaurant Casa Luca recalls of one group text message, about Washingtonian’s then head critic, Todd Kliman. The employee had left work early that summer evening, just a month or two after the restaurant’s 2013 debut. But the message was clear: Get back here. The employee was a block from Whole Foods, grocery bags in hand, with plans to cook a nice meal at home. Guess I should have eaten earlier, he thought as he rushed home to swap his shorts and T-shirt for a vest and tie. He picked up a Car2Go and drove to work “like a bat out of hell,” then scurried through an alley, past the loading dock, and into a back hallway. Restaurateur Fabio Trabocchi himself would come through the same back entrance if he got the critic call and wasn’t on-site.

“It was always an awkward moment trying to look like you’d casually been there the whole time,” the employee says.

This isn’t altogether uncommon. Especially for bigger restaurant groups in which not everyone is on premises, the director of operations, beverage directors, owner, and publicist are notified. Le Diplomate would sometimes call in friends to ooh and aah, within earshot of important critics, about how great everything was. Of course, the stunt doubled as eavesdropping: What did he say when the plate came out? Was he having a good time? The spies would text their observations to managers or slyly excuse themselves to go to “the restroom” and unload intel.

To communicate about a critic, some restaurants have their own code words. One Italian joint called Sietsema “Neapolitan,” because it didn’t sound too weird to say out loud in the open kitchen. Others, including the kitchens of Fabio Trabocchi, refer to Sietsema as “Papa Bear.”

“I heard ‘Papa Bear in the house,’ and it’s like a fire drill,” says a sous chef for one of Ashok Bajaj’s restaurants, which include Rasika and Bibiana. The sous chef was in the middle of butchering 150 pounds of salmon for a large banquet that night, but when the alert came in, sous chefs kicked line cooks off their stations and began preparing Sietsema’s lunch themselves. (In other kitchens, the executive chef might take over complete prep of a dish. That way, only one person is to blame if the review is terrible.) “It is a huge wrench in the operation, because what you’re basically doing is interrupting the regular flow of service to stop and concentrate on one table and the other tables surrounding.”

With the executive chef orchestrating, the sous chefs prepared triplicates of every component of every dish. Nerves, as always, ran high. “I’ve burned more shit trying to cook something perfect for Tom Sietsema than I ever would have if I didn’t know that he was there,” the sous chef says.

When the alert came in, sous chefs kicked line cooks off their stations and began preparing the critic’s lunch themselves.

Another source of dread: having to tell a critic you’re out of something. At now-closed Cashion’s Eat Place, if the kitchen was running low on a dish when a critic walked in, they’d tell the other tables it was eighty-sixed, just to be safe, says former co-owner Justin Abad.

The Adams Morgan restaurant would also save the center-cut pork chop or the nicest piece of fish for critics. “That’s the reality of things,” Abad says. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that per se. You’re in pursuit of excellence with each and every guest, but of course you’re going to stop and take a little more time.”

Along the way, he’d pause to record everything critics ate. Abad still remembers one evening when Sietsema ordered an ancho-chili-rubbed bison, cooked medium rare, with the chef’s play on A.1. Sauce. The critic ate only half the meat—which Abad worried was a little overcooked—but sopped up all the sauce. Abad notated everything on the back end of OpenTable’s reservation system, where restaurants can write private comments about guests.

At a couple of restaurants, bar owner Owen Thomson has seen chefs do more than inspect dirty dishes. On one occasion, Sietsema left more than half the food on a starter plate, and a busser brought the dish back to the chef. While restaurants tend to be fast-paced and frenetic, in that moment four or five people stopped what they were doing to look at it. Then the chef took a bite of the leftovers . . . and announced it tasted good.

“Generally, that’s pretty frowned upon,” Thomson says. Still, he kind of understands why some chefs get so crazy: “One, pride is involved. Two, I think people pay so much attention because no matter which way the review comes out, they want to be ready to explain themselves to whoever their boss is.”

Sometimes, though, restaurants can’t help themselves and insist on sending out freebies—even if it means they’re admitting that they know who the special guest is (and even though reviewers for reputable news organizations are generally not allowed to eat “gifts from the chef” without paying).

The former Trabocchi employee recalls one time when Sietsema dropped in solo for lunch at Fiola’s bar. He tried to treat the critic like a normal guest. Then a food runner dropped off a plate of tortellini with brown-butter sauce and an extra ingredient: a showering of black truffles.

I hope he doesn’t call me out on this, the employee remembers thinking when he saw the plate. He rattled off the description, improvising truffles into the script.

Sietsema, though, immediately noticed. “At a certain point, it just looks vulgar or like you can be bought,” he says now, recalling the incident. Plus, making dramatic changes can backfire on a chef if it gets written about and diners come in expecting the same.

Sietsema gave the employee a knowing look: “I don’t remember seeing black truffle on the menu description.”

The employee could think of only one thing to say: “Nor do I, sir. Nor do I.”

Which raises a question: Does all this Spy vs. Spy stuff matter?

At least a few restaurant people I’ve talked to insist that reviews skew more positive—at least half a star more—when staff succeed at spotting critics. “You read the reviews of some of these places, and you’re like, ‘Really?’ ” Thomson says. “At this point, it’s a rarity that they’re getting the same experience that a regular person gets.”

In recent years, as social media has made it ever harder to hide, critics at places such as New York magazine and the Los Angeles Times have dropped their disguises. Sietsema has thought about joining them. Part of him envies his colleagues who don’t have to duck away from photos at a party or who can have more direct access to the people they cover. But he’s worked so hard to try to remain unknown. Even at Starbucks, he gives another name.

And sometimes, a critic who uses the old bag of tricks can do work that really benefits diners. Sietsema re-reviewed the Friendship Heights restaurant Range after complaints from readers that their experiences weren’t like his. The second go-around, he transformed himself into someone else—complete with toupé and stained false teeth. The experience was so different that he docked the restaurant half a star.

Ultimately, though, the right server, a nice table, and the perfect filet help just up to a point. Restaurants can’t reinvent themselves on the fly. One manager of a small-plates restaurant told me how his place tracked critics’ alcohol tolerance, made duplicates of every dish, and brought in spies. But he said his tactics had their limits: “You can’t fake a four-star restaurant.”

Le Diplomate did not get another Sietsema review until eight months after that visit on Super Bowl Sunday. In the interim, there were more visits and more backstage ballets.

“I didn’t eat in Paris this year, but I did something almost as pleasurable: dinner at Le Diplomate, the best all-around French restaurant in the city,” Sietsema wrote. He praised the beautiful skate grenobloise and the splurge-worthy apple tarte Tatin. “The one inauthentic note is the service,” he concluded. “It’s warm and gracious, in the best American tradition.”

His rating: three stars.

This article appears in the December 2017 issue of Washingtonian.