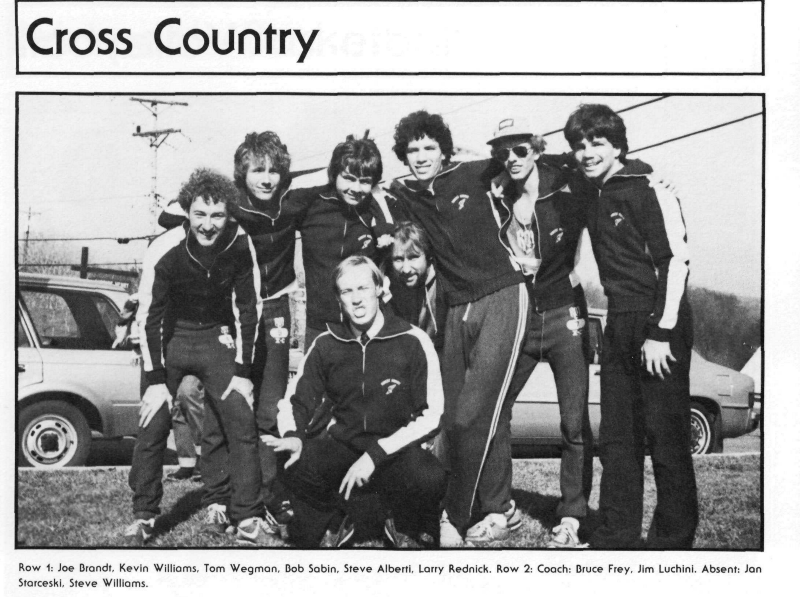

Sam Sabin’s father died while mountain biking in January 2015. His obituary listed his dogs but not her.

In the eight-part podcast series Good Grief, Sabin, now 23 and a reporter covering the tech community for DC Inno, attempts to answer questions that went unacknowledged her whole life. What she did know was this: Her parents split when she was 5, and she and her brother went with their mom. She and her dad remained estranged, and her whole life she wondered, “Why did he leave me and my family and never look back?” What she didn’t know about was the life her father returned to—a wife and three sons.

After encouragement from a professor and with funding from the UNC Creative Writing Program, Sabin started production on the podcast in February 2016 when she was a college senior, unsure of what the series would be about until, she says, around half-way through. From the obituary, she learned that her father, Robert “Bob” Joseph Sabin, was born in Syracuse and had been adopted. He was also half-Native American. (Sabin was asked by classmates in high school why she was taking Spanish since she “looked Hispanic.”) She says the first thing people often ask when you say you’re Native American is, “Which tribe?” She never knew the answer until she read the obituary: the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe.

The pilot opens with a solo road trip from Carrboro, North Carolina, to Akwesasne, New York, where the St. Regis reservation is located. When she gets there, she stays in a motel bed for two days, grappling with the fact that she would be entering the reservation with, she says, “a lot of white privilege, with this choice of whether or not I enroll. Because it’s not a choice for a lot of people.”

The series follows Sabin as she finally confronts her mom and later meets her half-brothers for the first time, over beers at an Irish sports pub in North Carolina. What elevates Sabin’s story of grief from a deeply personal, singular one are its frequent relatable moments. The final episode, “Father’s Day,” opens with her saying, “I wish I could say it took me longer to find this.” To hear this, it sounds as if she’s speaking about the journey to the final episode. But she’s standing before the tree that her father crashed into after having a heart attack. She doesn’t know what to say. The hike quite literally didn’t take as long as she thought it would. In some ways, neither did finding the answers. Looking at a plaque on the tree memorializing her father, she says, “I bet you never thought I’d be here, but… It’s a pretty place to die.”

Since debuting last December, Sabin says the response to Good Grief has been powerful, mostly from those grieving as well. There’s the nurse from Boston who works with addicts and tried to help her sister, addicted to opioids, but couldn’t. She overdosed in November. There’s the mother from Austin who lost her son last year in a car accident and copes by smashing plates in an empty parking lot at midnight. They’re stories, says Sabin, “that sit with you.”

In January, Sabin starts production on the second season of Good Grief, which will tell others’ stories. “I think grief stories—and it’s ridiculous—typically put people’s emotional journeys into these little buckets,” she says. “You go through that period, that quote-unquote five stages of grief, which are kind of bullshit. There’s not just steps you go through—there’s things you bounce between all the time.” For the individuals she’s worked with so far, one commonality is that—despite the five stages being bullshit—all have reached acceptance. “You go through them, until you truly accept it and go oh, okay, this is how I live now, this is who I am. This is how I’ve changed from it.”

To submit your story of grief or connect with Sabin, visit her website here.