Robert Adler was a thirtysomething attorney at a small Washington firm in the late 1970s when a woman arrived in his office to discuss her problems at work. The woman, Sandra Bundy, was an employment specialist at DC’s Department of Corrections, where she helped former inmates find jobs after their release. About four years earlier, she explained, her superiors had begun making repeated—and unwanted—sexual advances toward her. After she rebuffed them, things got worse. When she complained to a more senior manager about the treatment, he said he couldn’t blame a man for wanting to take her to bed. “Let’s talk about you and me,” he later said. “When are we going to get together?” Appalled, she reached out to the director—a man who had also propositioned her in the past. He was of little use.

Bundy, a single mother, had joined the city government because it offered opportunities for advancement that she needed to support her children. She was, Adler recalls, a “smart, elegant, tough lady.” But the harassment had left her badly damaged. Could the young lawyer help?

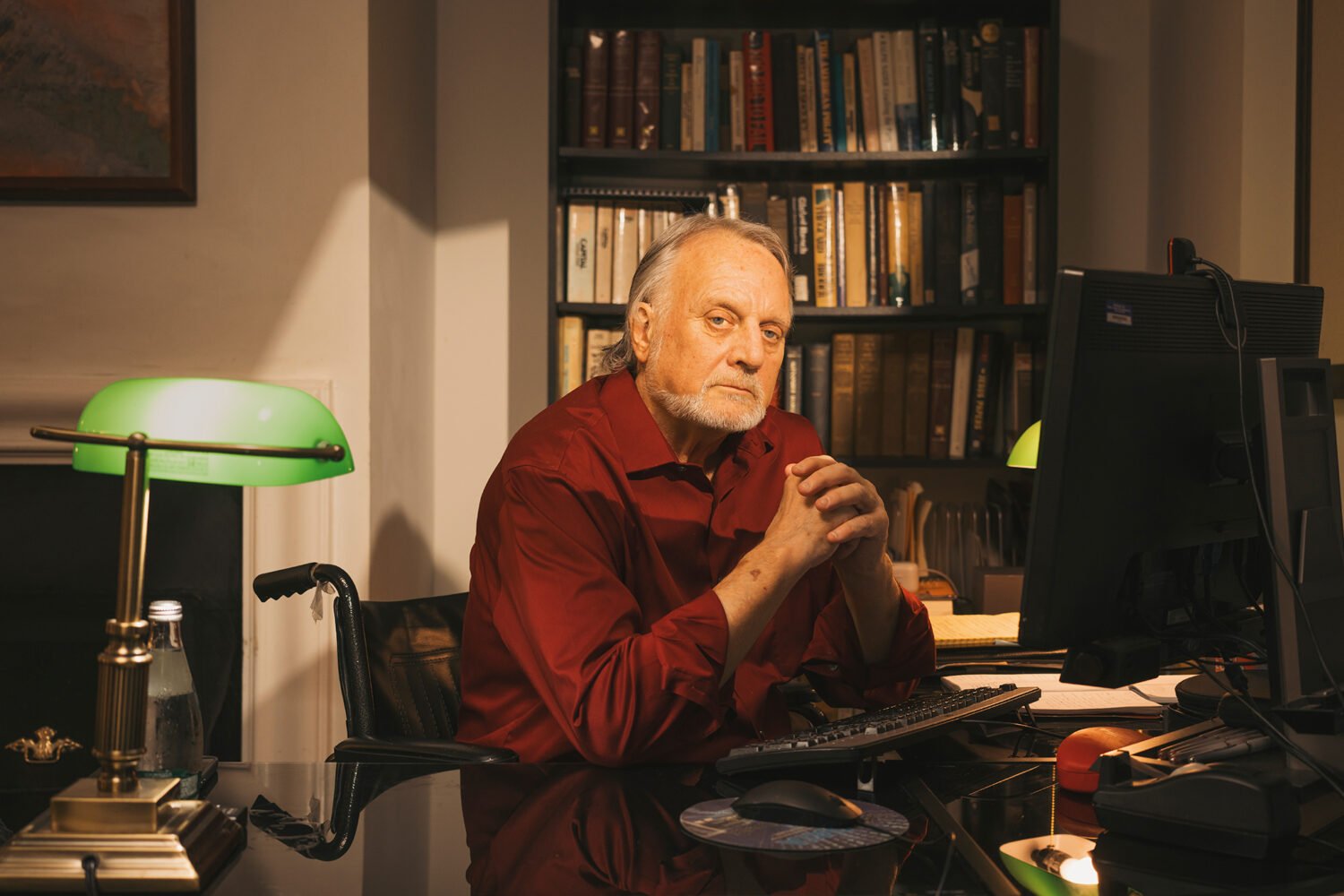

Adler was an odd choice for the assignment. In the few years since launching his firm, he’d handled personal-injury cases, breach of contract, and divorce—never anything like this. Worse, Bundy’s claims fell into a legal gray area. She hadn’t been sexually assaulted or been denied employment because of her gender. Instead, she’d experienced a form of abuse not yet written into American law. Taking her case would be a tedious, expensive, and uncertain endeavor, requiring Adler’s team to argue new legal theories—with little financial upside.

As Adler listened to her story, however, he felt compelled to act. In 1977, Bundy sued the director of the Corrections Department in federal court. “I had no optimism that we were going to win this thing, because we were really in uncharted waters,” Adler says. “But I didn’t care.”

Today, some 40 years after she first walked into Adler’s office, Bundy’s lawsuit is considered a seminal event in the establishment of sexual harassment as a legal concept in America. “What is so incredibly significant about the case was finding that sexual harassment itself—the doing of it—was sex discrimination,” says Catharine MacKinnon, a University of Michigan law professor and a leading scholar on the issue. “That has been world-changing.”

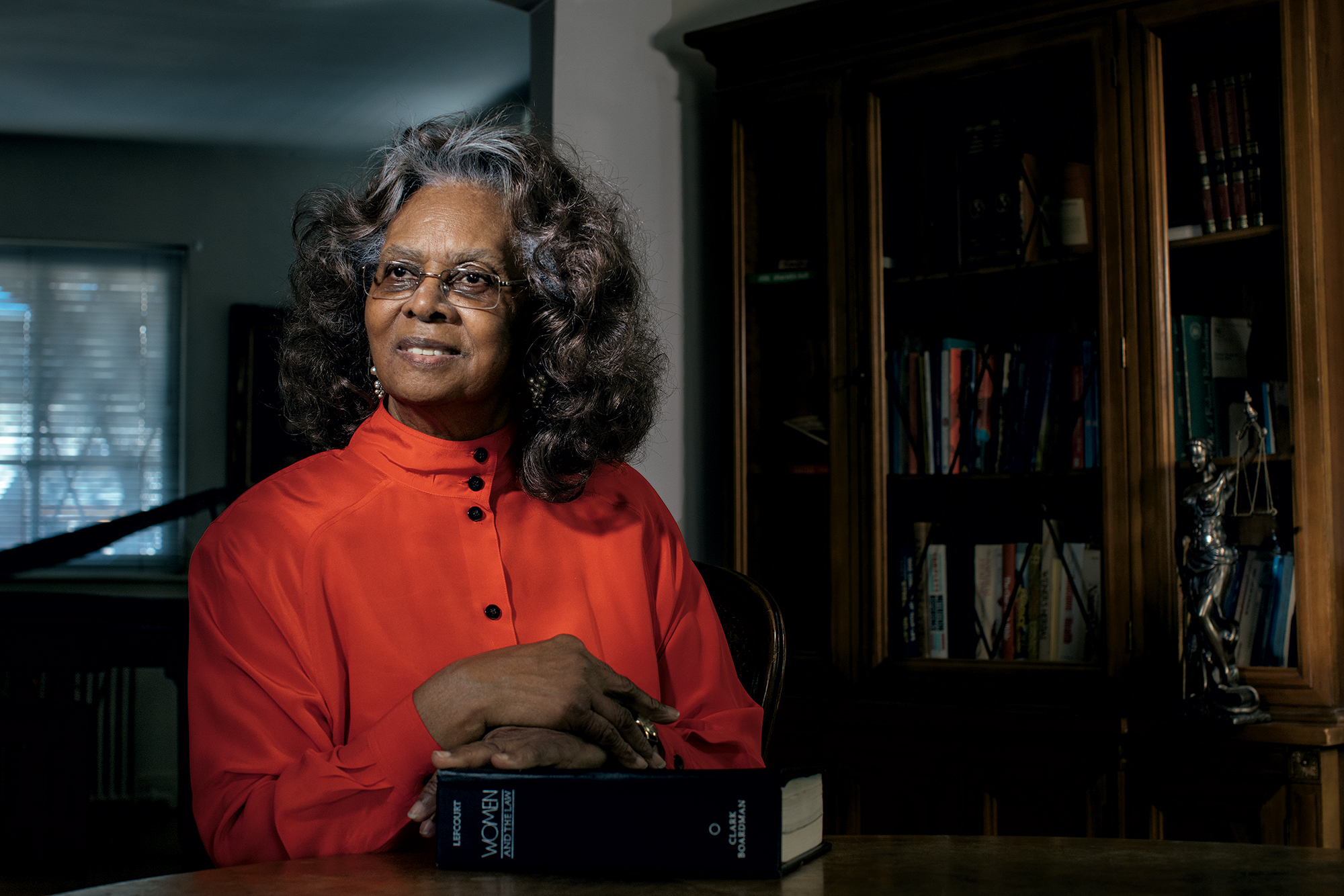

Yet even as the #MeToo movement has exposed abusers of power in politics, Hollywood, and the media, the women who pioneered the legal protections against such harassment—Bundy and three fellow African-Americans, all from Washington—have remained anonymous figures. This is the story of how one of those women survived a crucible of misogyny, took on her abusers, and made history.

“I had to protect my family, and I had to protect my livelihood,” says Bundy, now 84. “So I had to fight.”

Sandra Bundy is warm and chatty, with thick shoulder-length hair and wire-framed glasses. She lives in DC near Catholic University, in a red-brick house lined with photographs of her family. Beside the fireplace, there’s a piano that she likes to play. Her favorite pastime, however, is working in the garden out back—watering the shrubs along the patio, pruning the roses that climb the trellis, and watching the mums bloom each fall. “All of this,” she says, “is therapy for me.”

Bundy grew up in Washington and graduated from Armstrong Technical, a now-closed District public high school, in 1952. Her father had walked out on the family when she was a child, and the absence of a loving male parent, she believes, led her into unhealthy marriages. Two husbands beat her badly enough to cause concussions. By age 33, she’d had five kids and been married five times, and because none of her exes had paid child support, Bundy was on her own to provide for her family. One afternoon six years earlier, a teenager whom Bundy had hired to watch her children while she was at work didn’t show up, and her three-year-old daughter wandered away to play with a neighborhood boy of about the same age. The boy, who was fiddling with matches, lit the girl’s dress on fire. Bundy’s daughter died from the burns.

At the funeral, Bundy went into shock and came to only after being submerged in a bathtub of cold water. Despite the trauma, she couldn’t afford to take time away from work. “I knew I had to be the one to stay strong,” she says. “So I fought through it all.”

By the late 1960s, Bundy’s finances were disastrous. She worked as a clerk for the US Department of Commerce during the day and as a cashier at Giant at night, but it wasn’t enough. Creditors hounded her, she fell behind on rent, and she filed for bankruptcy. When her boss at Commerce said she didn’t have enough education for a promotion—she’d studied for two years at what’s now the University of the District of Columbia but hadn’t completed her degree—she began looking elsewhere. That’s how she learned that the city’s Department of Corrections was hiring.

She started in 1970, and at first the new career suited her well. She was promoted from personnel clerk to employment-placement specialist, and she found the work with ex-convicts satisfying. She soon earned $10,500 a year—more than double her starting salary at Commerce and enough to quit her second job.

One morning in the spring of 1974, Bundy’s supervisor, a man named Arthur Burton, summoned her to his office. The two chatted about their weekends, and Bundy explained she’d been horseback riding. According to an internal memo she filed in 1975, Burton said he’d read in a book that “women who ride horses have strong sexual drives and riding horses gives them sexual relief.” He certainly wouldn’t want to bring literature like that to the office, so perhaps she might like to come to his apartment to see it? Absolutely not, Bundy replied. On several subsequent occasions, according to her court testimony, Burton asked if she wanted to knock off work and meet him at his place. Each time, Bundy refused.

Then one evening, Burton called her at home to see about getting together. The call rattled Bundy, because her phone number was unlisted. She started to explain that she wasn’t interested, but “before I finished the sentence,” she said in a memo, “Mr. Burton slammed the phone.”

Around this time, James Gainey, a colleague of Bundy’s who became her supervisor, was pursuing her even more aggressively. According to court documents and testimony, he patted her behind, called her a “fine Momma,” and invited her on a trip to the Bahamas. He also told her, “I’ve got a pocketful of money. Let’s take the afternoon off to a motel and lay up.”

And: “I have been trying to get you to go to bed and you have been turning me down. What’s wrong with me?”

She refused each advance.

After she’d rejected them again and again, the men began treating Bundy differently. When she’d first arrived in the office, the environment had been laid-back. “[Burton] was telling me not to put as much emphasis in my job,” Bundy said in a deposition. “Told me not to spend too much time with my clients. Just relax, you don’t have to do that much.” Now he wasn’t so accommodating—he started singling her out for taking too many days off and criticized her work. At one point, he threatened to fire her. Later, Bundy learned she’d been overlooked for a promotion while her male colleagues had moved up or been recommended. On the advice of a female colleague, she began keeping a diary that detailed the mistreatment.

Convinced that her jilted superiors were out for revenge, Bundy contacted Lawrence Swain, a senior manager. They’d gone to a dinner dance once, and although he hadn’t made any passes at her that night, she’d refused to go out with him again. Bundy told Swain she had drafted a letter describing Burton and Gainey’s harassment and that she was considering filing a formal complaint against the agency. Swain pleaded with her not to release the letter, and he promised to speak with Burton first thing the next day.

“Is that all you want to talk about?” Swain asked, according to Bundy’s testimony.

Yes, she said.

He didn’t seem to understand what all the fuss was about, telling her, according to her testimony, “Any man in his right mind would want to rape you.”

When things didn’t improve, Bundy decided to go back to Swain. Although she’d been horrified by his comments, he was the next-highest figure in the chain of command, so she felt obliged to try again. “I will get it straightened out,” she testified that he told her. “Don’t worry about that.”

Then Swain asked her a question: “Are you still seeing that fellow that you were seeing before?”

“Why?” Bundy replied.

“Because if you are not,” he said, according to her testimony, “I want to take you to bed myself.”

Again, Bundy rejected the advance.

Over time, the harassment left its mark. Bundy had trouble sleeping, and her appetite vanished. After work, she often returned home to her apartment in Silver Spring, cloistered herself in the bedroom, and cried. One night, she considered jumping out of her tenth-floor window. She eventually began seeing a psychiatrist, who prescribed medication for depression and anxiety.

There was one person who might be able to help: director Delbert Jackson, the most powerful man in the department. Yet he, too, had a history of coming on to Bundy. In 1973, according to one of her memos, he had asked her out three weekends in a row. One Friday night, for example, he invited her to come to his apartment for drinks. When she explained she didn’t drink, he replied, “Well, that’s all right,” according to Bundy’s testimony. “We can find something to do to relax.” She turned him down as well.

Still, she had no choice but to go to Jackson—he was the top official on the org chart. In April 1975, the two met and Bundy said she was ready to move forward with a formal complaint. “I couldn’t take any more,” she later testified. Jackson urged her to hold off, and he arranged for her to meet with a group of top managers to hash things out.

“Any man in his right mind would want to rape you.”

Three days later, she returned for the meeting, only to find that three of the five supervisors present had either propositioned her or asked her for dates. “I was certainly embarrassed again having to spell out all of these things,” she testified, “in the presence of the men that these allegations were directed at.” Bundy shut down, too uncomfortable to bring up the abuse. The supervisors, meanwhile, eventually claimed she’d been denied the promotion because of shoddy work—criticism they hadn’t voiced until she rejected their advances.

Bundy became convinced she’d never get justice from the inside. When she met with the agency’s Equal Employment Opportunity officer, he said her allegations might be difficult to prove and warned her against bringing false claims. Out of options, she began asking friends if anyone knew a good lawyer.

Robert Adler, thin with dark curly hair, scoured the library for sexual-harassment lawsuits with his team, hoping to assemble a playbook of winning arguments to use in Bundy’s case. They found little to be encouraged about. “Most of the case law was going to go against us,” says Arthur Chotin, the attorney who argued the case at trial.

At that time, judges took it for granted that men would pursue women at work just as they did at the local bar—and “there was nothing the law could do about it nor should do about it,” says Gillian Thomas, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project. In her book about landmark discrimination cases, Because of Sex, Thomas cites a New Jersey judge who ruled against an early harassment claim by saying the law wasn’t meant to “provide a federal remedy for what amounts to a physical attack motivated by sexual desire . . . which happened to occur in a corporate corridor rather than a back alley.”

There were, however, two women from Washington who had faced similar harassment, taken their abusers to court, and scored historic legal victories.

Diane Williams, a 23-year-old single mother, had joined the Department of Justice as a public-information aide in 1972. At first, she had a good working relationship with her supervisor. But after she turned down his advance, he fired her. “It’s demoralizing,” Williams told author Lin Farley in the 1978 book Sexual Shakedown, “and there is this inescapable feeling of being responsible because you are being punished.” (Williams died a couple of years ago, according to her lawyer, Michael Hausfeld.)

Williams sued the head of the Justice Department in federal district court in DC, arguing that her supervisor’s treatment was illegal under the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which bars employers from discriminating against workers on the basis of religion, race, national origin, color, or sex. Until then, judges had taken a narrow view of the statute, ruling that it protected women only from sexual discrimination in its most conspicuous forms, such as being denied a job on account of their gender. But in Williams’s case, the court concluded—for the first time—that the Civil Rights Act also shielded employees from retaliation for refusing their superior’s sexual propositions.

Around the same time, Paulette Barnes was working as an administrative assistant at the Environmental Protection Agency when her supervisor began asking her out, making sexually suggestive remarks, and implying that going to bed with him would benefit her professionally. When she refused, he eliminated her job. Although a judge initially ruled against her, the federal appeals court reversed the decision in 1977, reiterating—this time at an even higher court—that such treatment was unlawful under the Civil Rights Act. (Barnes, who lives in Prince George’s County, was unable to comment for this story.)

Bundy’s legal team settled on a similar approach. In July 1977, Adler’s firm filed a suit against director Jackson under the Civil Rights Act, demanding back pay for Bundy’s delayed promotion.

The trial began on March 12, 1979—Bundy’s 45th birthday. She arrived in court feeling nervous about facing her harassers, “but in the back of my mind, I kept saying, ‘I’m going to tell the truth,’ ” she recalls. “I was going to stand up for all that has happened.”

Over the next three days, she absorbed the suspicions and indignities familiar to sexual-harassment victims everywhere. The men denied making sexual advances, according to court testimony; Jackson said Bundy had asked him out, not the other way around. Although Bundy had received “satisfactory” evaluations and her coworkers testified that her performance was on par with theirs, various agency officials took the stand to point out times she’d been late to meetings or failed to file reports properly. Jackson’s lawyer, Alexandra B. Keith, even raised the issue of Bundy’s love life with her opening question: “You have been married five times?”

One senior official, Claude L. Burgin Jr., testified that Bundy had invited explicit remarks from ex-cons by, on at least one occasion, wearing a low-cut outfit: “I said, ‘Mrs. Bundy, you are a very attractive woman, but dressed the way that you are, you will solicit words or advances from people that you should not have to be bothered with.’ ”

As the case played out, Bundy was confronting new hardships at work. She says her superiors transferred her to the department’s prison complex in Lorton. Instead of working with ex-cons in an office setting, she was suddenly a uniformed corrections officer responsible for keeping order among violent criminals—a reassignment she believes was designed to intimidate her. “They didn’t think I could handle the job,” she says.

After three days of testimony, Judge George Hart announced his decision in April 1979. He concluded that Bundy’s “superiors appeared to consider the making of improper sexual advances to female employees as standard operating procedure, a fact of life, a normal condition of employment in the office.” Propositioning subordinates was “a game played by the male superiors—you won some and you lost some. It was not a matter to be taken seriously.”

However, he also ruled that Bundy’s promotion had been delayed not because she’d refused these advances but on account of her work performance. This distinction decapitated Bundy’s entire claim. Diane Williams’s and Paulette Barnes’s cases had established only that it was illegal for higher-ups to retaliate against employees for declining their sexual advances—what’s known as quid pro quo sexual harassment. No court had held that the Civil Rights Act protected workers from sexual harassment that didn’t involve the loss of so-called tangible job benefits. The straightforward act of making repeated, unwanted advances or lewd comments—what’s known today as creating a hostile work environment—was still perfectly legal. Judge Hart concluded that director Jackson “did not discriminate against [Bundy] on the basis of sex in any term or condition of her employment.”

Bundy took the news hard, but her lawyers resolved to press on. “There was no factual dispute here. The dispute was: Is this a violation of the law? Is this not a violation of the law?” says attorney Arthur Chotin. “It was clear to us that what had happened to her was wrong, and we were committed to taking it as far as it needed to be taken.” One month later, they asked the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to revisit the decision.

Unlike other courts that had heard harassment cases, the DC circuit had a progressive tilt. Judge Spottswood Robinson was a former civil-rights lawyer who’d helped lay the groundwork for the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Chief judge Skelly Wright’s rulings had led to the integration of public schools and transportation in Louisiana when he’d served as a federal judge there. His desegregation orders had made him so reviled by Southern whites that police officers had had to protect him.

Judges took it for granted that men would pursue women at work just as they did at the local bar.

In January 1981, Robinson, Wright, and a third judge on the appellate panel reversed the lower court’s decision, saying that other courts had already determined that racial and ethnic discrimination was illegal under the Civil Rights Act because it “poison[ed] the atmosphere of employment.” If the appeals court didn’t extend the statute’s protections to circumstances like Bundy’s, “an employer could sexually harass a female employee with impunity by carefully stopping short of firing the employee.”

Bundy was thrilled. “I felt mentally and emotionally relieved,” she says. “These things will stop. I won’t have to go through it any longer.”

The decision reverberated in ways Bundy never imagined. In 1986, the Supreme Court upheld the legal principles that Bundy—along with Paulette Barnes and Diane Williams—had helped pioneer. As it happened, that decision involved another case from Washington. In Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, the justices established once and for all that sexual harassment was an illegal form of sex discrimination. Bundy, says employment lawyer Debra S. Katz, had “paved the way” for this landmark event.

Robert Adler is still practicing law in Washington, as a partner at Nossaman. Although he primarily handles white-collar matters, he still makes time for everyday Washingtonians. Last October, he secured a $90,000 settlement for a woman who had been a secretary in the 1980s when she was demoted, she claimed, for refusing a superior’s advances. The case had dragged through the courts for 27 years. The woman’s employer? DC’s Department of Corrections.

When her lawsuit ended, Bundy enjoyed a dash of attention. Her case was written up in the Washington Post and the New York Times. But although she received several thousand dollars in back pay, the court couldn’t give her what she really wanted: a return to the job she had loved. Instead, she says she was transferred from the Department of Corrections to another city government office, where she spent her days checking District-owned buildings for asbestos. She believed she’d been dumped into another undesirable job on account of her lawsuit, but by then she was too worn down to battle for a reassignment. “I just got tired of fighting,” she says. She stayed in the office until 1991, when she retired from the city.

As she watched her children grow up and have kids of their own, the events that had brought her to Adler’s office became less resonant in her life. Still, from time to time, the memories resurfaced, and they hurt. “I used to think back on those things, and I used to cry,” she says. “It was so depressing.”

But as she watched #MeToo hashtags explode into the national zeitgeist last fall, she became overwhelmed by feelings of a different sort. Solidarity with the women standing up to workplace sexual misconduct. Pride in her contribution to the effort. And hope that no other single mother would have to endure what she went through.

Says Bundy of the #MeToo silence breakers: “I’m happy I’ve lived this long to see it.”

This article appears in the March 2018 issue of Washingtonian.