Maria Shapiro is really excited about computers. When we meet in a Rockville Whole Foods, she’s sitting with what looks like a small computer chip with wires and lights connected to it. When I ask what it is, her face lights up when she explains it’s an Arduino, a piece of hardware she uses to teach about programming and circuits. Later she turns it on and the light bulbs illuminate in a pattern controlled by a program she wrote.

The senior at Potomac’s Winston Churchill High School has exhausted her own school’s computer science curriculum and has been trying to spread her love of technology to elementary schools across Montgomery County. She founded E&P, an organization that volunteers to teach two-day, elective after-school technology workshops.

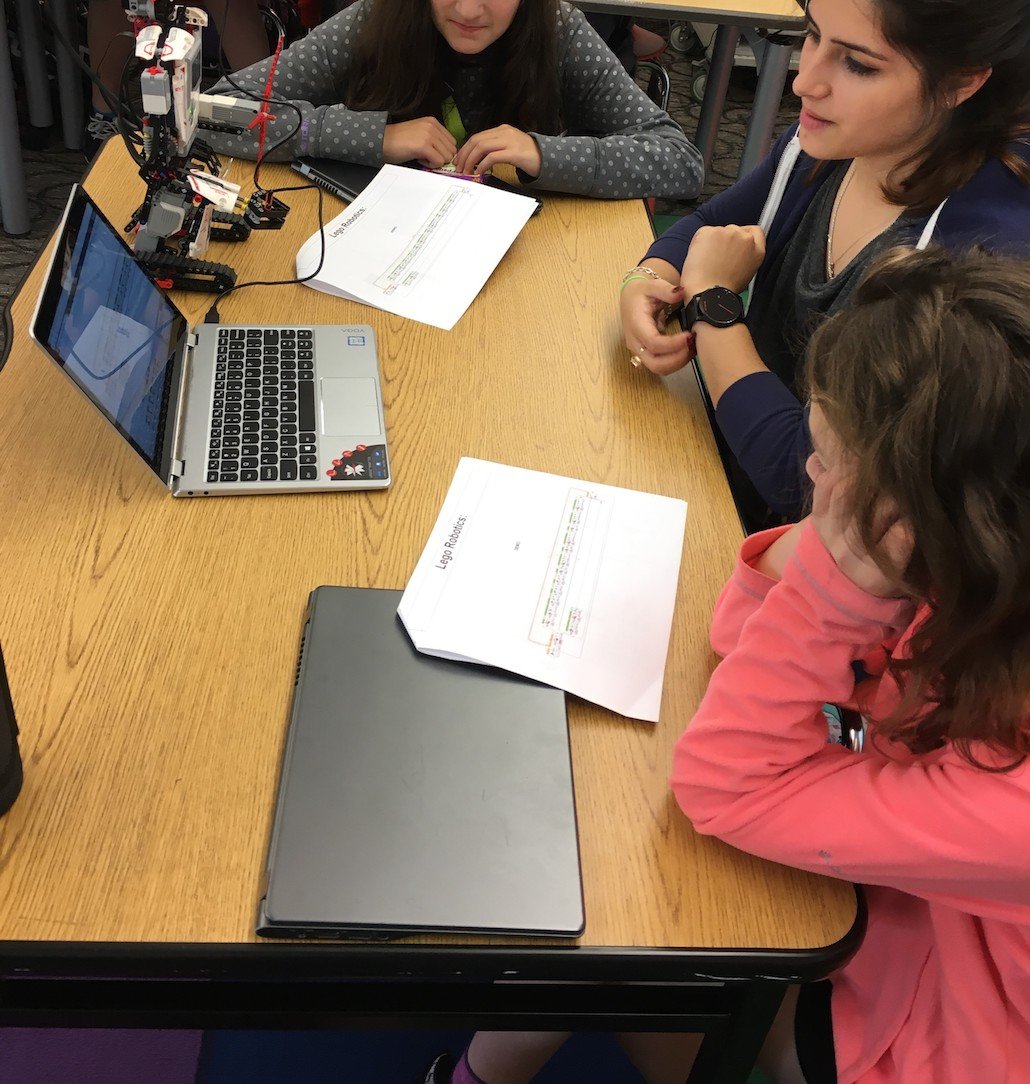

Shapiro and her current co-teaching partner Sid Ajay, who also attends Churchill, give students a taste of programming, cybersecurity, and even dabble in a bit of robotics. One day the duo brings in cool technology—like a small robot and a VR headset that simulates riding a roller coaster—and the next day, they conduct a hands-on intro to programming work.

It all started in 2014 when Shapiro was a high school freshman, and her fifth-grade teacher at Bethesda’s Seven Locks Elementary School asked whether she could give a few students some after-school tech help. There ended up being a lot of student interest, and since then, she’s taught in several schools. Currently, she’s working with Glen Haven Elementary School in Silver Spring.

Shapiro, president of her school’s Engineering Honors society, has learned several coding languages. But converting every kid into a future software engineer isn’t the program’s aim. Rather, she’s trying to expose kids to technology and get them excited about its possibilities.

“It’s mainly to spark a passion,” she explains. “Perhaps you’re not going to go into computer science or you don’t even like technology. That’s perfectly fine. But the skills of critical thinking, computational programming, it’s going to help you. Especially jobs in 10 to 15 years, everything includes technology.” Clarksburg Elementary School principal Carl Bencal says that E&P taught at his school last year, there were almost too many kids interested in participating. “Our kids love tech anyway but when coming from someone young and passionate it fires them up even more,” he says.

Shapiro says that while the kids who take her course are usually evenly split between boys and girls, she hopes her presence as a leader is especially encouraging to young girls.

E&P’s work in local schools is under a division called “Kid 2 Kid,” as Shapiro and her co-leader are working with students not much younger than them. But they also have an international initiative. Shapiro explains she’s half Pakistani and half Polish, and when she visited her grandparents in Poland, she noticed that the small local school there didn’t have great access to technology education.

“Even with the then limited programming knowledge I knew then, I could do something for people around the world, she recalled. “I could make a difference. That’s what I did.” So in 2016 she taught in two Polish schools, exposing them to programming while helping improve their English as well. That’s where the groups name E&P, standing for English and Programming, originates.

A current high school senior, Shapiro has plans to go to college next year, probably to study computer science and business. But that doesn’t mean the end for E&P. The group’s been working on getting more schools on board and trying to become an official nonprofit organization.

Shapiro has big dreams for the group’s future—namely expansion and a broader reach. “I want to make a general curriculum and have some of these worksheets and add some more people to the team,” she says, “And they go back to their own hometown and their own roots and they teach there. So it kind of becomes an international thing. Helping alleviate the barriers in technology and language, and also connecting back to who you are and what your roots are.”