It’s an unseasonably warm morning in the spring of 2015, and I’m running in my suburban Virginia neighborhood. Purple-red dye is oozing down my face and neck, spreading across my shirt, and staining my chest.

I am a creature of routine. I run every morning. But this morning began differently. After pouring my usual glass of water, I headed into the bathroom and looked in the mirror.

My roots are showing, I thought. I need to dye my hair. Now!

I got out some henna from Whole Foods that I love and that gives my hair a funny purple tint. I mixed it in a cup, then squirted it onto my scalp and spread it on my head. I pulled a plastic bag over my skull and tied it with a little knot on one side to hold it in place.

Now I’ve been out here running for hours, and I have no idea where I am. I don’t recognize the streets or the houses, even though I’ve lived here 20 years. I want to get home but can’t find my house. So I simply keep going, covered in gore.

Somehow, I finally come upon our two-story Colonial. Tired and sweaty, I take off my sneakers and socks, which are completely soaked. On my way upstairs, I glimpse myself in a mirror. My head is caked in sweat mixed with hair coloring, the plastic bag plastered on top like a weird swimming cap. Streaks of purple dye, long since dried to black, have crusted in thin rivulets down my neck and upper arms and all over my shirt.

Nothing strikes me as unusual.

In his home office, my husband, Mirek, is at his computer with his back to the door. When he hears me enter the room, he says, “You’ve been away a long time. Good run?”

Then he turns to me with a smile—and freezes.

“What happened?” he exclaims.

“What do you mean?” I say. “It was a long run.”

“Did anybody see you like this?” He seems shaken.

“Why would I care if someone saw me? What are you talking about?”

“Wash it off,” he says. “Please.”

“Calm down, Mirek! What are you going on about?”

What’s wrong with him? Why is he acting so strange?

Mirek’s behavior should be a red flag, a clue that something is terribly wrong. But a moment later, the unpleasant thought simply slips through the cracks of my mind and is gone.

I am a neuroscientist. As director of the Human Brain Collection Core at NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health, I manage a library of brains that for any number of reasons didn’t work the way they should have. Brains that saw hallucinations, heard mysterious voices, were buffeted by wild mood swings, or were deeply depressed. Brains that have been collected, catalogued, and stored here for the past 30 years.

First thing each morning, the technicians in our brain bank telephone local medical examiners’ offices and ask, “Do you have any brains for us today?” Once they’ve compiled their list of candidates, they come to me, and together we narrow it down. Do we want this one, a drug overdose? Or this one, an alcoholic? If there’s any possibility that a brain may be right for us, I usually say yes. Our job is to cut the organs open and study their inner workings in an attempt to understand mental illness. The brains we seek are rare and precious, and we don’t get nearly enough.

I’ve worked with brains for more than 30 years, starting in rats. As a neuroscientist and molecular biologist, I’ve spent my career, first in my native Poland and then in Bethesda, trying to solve the mysteries of schizophrenia, a devastating disease in which it can be difficult to distinguish between what is real and what is not. My most significant discovery implicated the brain’s frontal cortex as an essential site for the development of schizophrenia. It became known as the Lipska model. It has been described in hundreds of scientific papers, replicated in labs around the world, and applied to other research areas, including genetics and cognition. It has been of help in designing new drugs.

All this recognition is what led to me being named the brain bank’s director in 2013. By that point, everything seemed to be going right. My two children were grown and married, raising kids of their own. I was still biking 20 miles to my office. Every night at dinner, Mirek and I would sit on our elevated back porch in Annandale as if on the deck of a ship sailing through a green sea of woods and grass. We would revel in the many birds around us—woodpeckers, hummingbirds, tiny wrens—and feel exceedingly content with life.

But very soon, I would begin to wonder whether the rats from my early experiments were exacting their revenge on me. The same brain structure that I’d sabotaged in thousands of rodents would begin to malfunction, spectacularly, in my own brain, thanks not to schizophrenia but to a series of tumors. Cancer, it turns out, can cause you to lose your mind. And even though I of all people was equipped to recognize that, I had no idea what was happening when I lost mine.

One morning several months before that fateful jogging trip, I sat down at my desk and began to eat a bowl of oatmeal. I reached to switch on my computer. My stomach clenched. My right hand is gone.

I couldn’t see it. It had disappeared.

I moved my hand toward the left.

There it is! It’s back!

But when I slid it back to the lower-right quadrant of the keyboard, it vanished again. It was like a freaky magic trick, mesmerizing, frightening, and totally inexplicable—except . . . .

Brain tumor.

I immediately tried to push the thought from my mind.

I had beat Stage 3 breast cancer in 2009 and Stage 1B melanoma in 2012. But both cancers often metastasize to the brain. I knew that a tumor in the occipital lobe, the area that controls vision, was the most likely explanation for this bizarre vision loss. I also knew that metastasis is horrifying news.

I Googled to see if the problem could be a side effect of a medication I was taking. Okay, yes, that’s a possibility. But . . . it could also be a brain tumor.

I was supposed to leave the following day for a ski trip and work conference in Montana, but on some barely conscious level, I knew my situation was dangerous. I went to see our family doctor. “I don’t think it’s your eye,” he said. He sent me to the ophthalmologist across the street. She found nothing wrong with my optic nerve or retinas, no cataracts. But when she leaned back, her eyes were sad. “I’m afraid it’s in your brain,” she said. “We need to do more tests.”

Mirek was waiting for me back at our doctor’s. He’s an intellectual, unfailingly kind and warm, with a wry but gentle sense of humor. I have a strong personality, loud and laughing and stubborn about my opinions, but Mirek loves me just the same. I looked to him for comfort as our doctor said, “We have to do an MRI of your brain as soon as possible.”

The next day, the scan found three tumors. One was bleeding.

My melanoma was back, and my prognosis was dire. When skin cancer spreads to places such as the lungs, liver, or brain, it’s almost invariably terminal.

All the while, I was losing my grip on reality, oblivious.

My family was well equipped to help me figure out what to do. My son, Witek, is a neuroscientist; my daughter, Kasia, is a physician; my sister, Maria, is a physicist working in radiation oncology; and Mirek is a brilliant, logical, cool-headed mathematician. We decided I would have stereotactic radiation surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston, in which they’d shoot my tumors with precise, high-energy radiation beams in the hope that the growths would wilt into nothingness. The problem was that targeted radiation is not a permanent solution. If new tumors continued to appear, my brain would soon be riddled with deadly lesions. I needed to do something dramatic, find something cutting-edge to save my life. Without it, I would be dead in a matter of months.

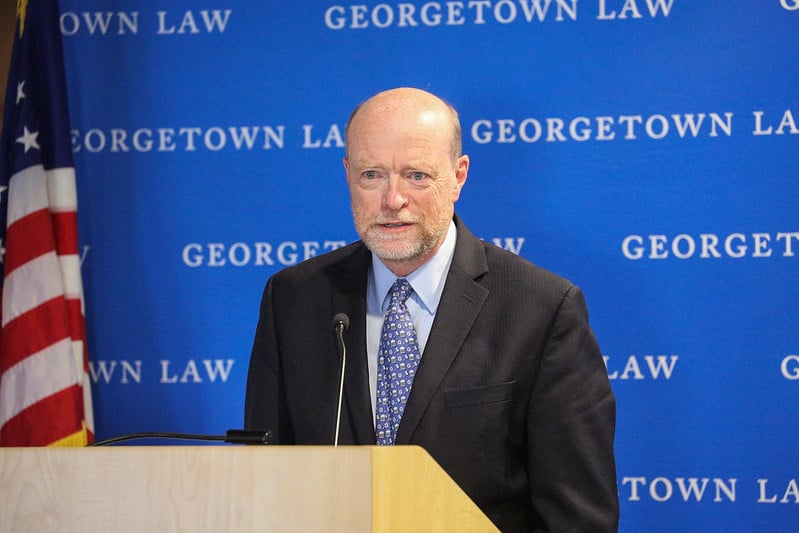

As it happened, an immunotherapy clinical trial was just about to open at Georgetown University Hospital’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center under the direction of a highly regarded oncologist, Michael Atkins. As part of the treatment, every three weeks a combination of two monoclonal antibody drugs, called checkpoint inhibitors, would be simultaneously infused into the veins to boost the immune system. There was a spot in the trial for me. But while the chemicals would alter my T-cells and take aim at the cancer, something else would start happening to my behavior.

I got my first infusion in April 2015. Sometime after the second one, my body turned on me. My immune system went on high alert and began to attack not just the tumors in my brain but also healthy tissue throughout my body. My skin bothered me the most. From my scalp to my feet, I was covered in a red, itchy rash. It was miserable, but pretty standard immunotherapy side-effect stuff.

I decided to take my mind off things with a trip to New Haven to see my daughter and her family. The train rumbled slowly across Maryland and New Jersey. Then, in the middle of nowhere, it stopped. After a moment, the lights and AC went out. I tried to be patient and relax, but my discomfort increased as the delay grew. Finally, after at least half an hour, the conductor announced that a tree had fallen on the tracks. We were waiting for maintenance.

It ended up taking seven hours to get to New Haven instead of the usual five. When I arrived at Kasia’s, my grandsons jumped all over me and Kasia kissed me. I wanted to feel her warmth, to let her know I’d missed her and was happy to be with her. But that’s not what I said.

“Amtrak sucks!” Those were the first words from my mouth.

She looked a little shocked.

I carried on, complaining about the train, begging for her sympathy as she implored me with her eyes to let it go. “Amtrak sucks!” I said it again. And again. For the next two days, I couldn’t stop talking about my train ride. I brought it up with Kasia and her husband, Jake, and their friends. Amtrak sucks! The refrain circled around in my mind like a toy train looping a closed track. And it wasn’t only the railway.

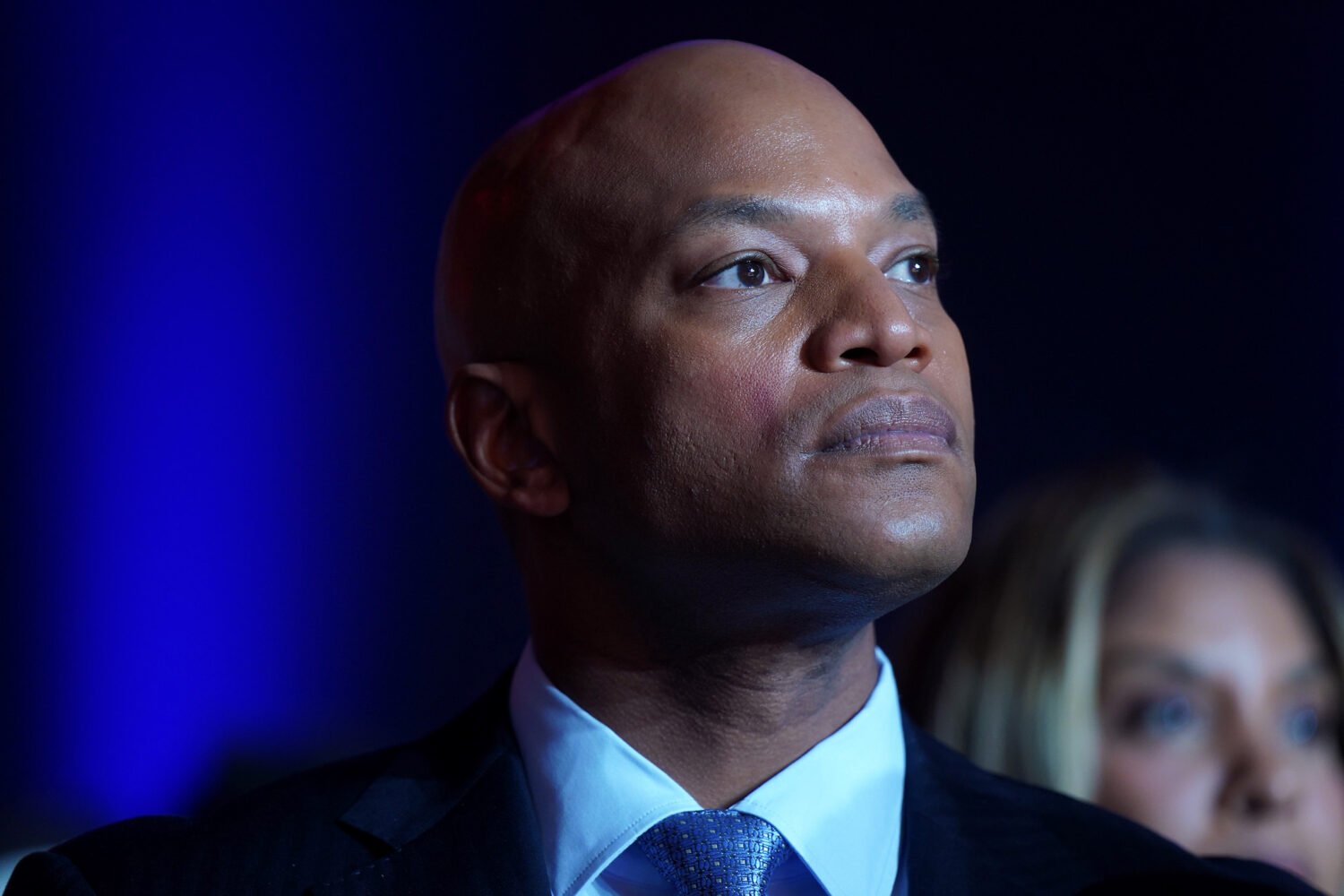

A marathoner and triathlete, Lipska used to bike 20 miles to her office in Bethesda from her home in Annandale.

A marathoner and triathlete, Lipska used to bike 20 miles to her office in Bethesda from her home in Annandale. She enrolled in a clinical trial, but the treatment wreaked havoc on her mental health—as her family watched in horror. Photograph courtesy of Barbara K. Lipska.

She enrolled in a clinical trial, but the treatment wreaked havoc on her mental health—as her family watched in horror. Photograph courtesy of Barbara K. Lipska.I became irritated if our lunch was even five minutes later than Kasia promised. I couldn’t stand how loud the boys were. I found everything my family did annoying, and I told them so. On the second afternoon of my visit, my eight-year-old grandson, Sebastian, came running over, laughing loudly, and bumped into me. It pissed me off. “Be quiet!” I told him. “Just stop it!”

He looked as if he were about to cry. “You’re so mean!” he said.

“Oh, come on!” I shot back. “You can’t be that sensitive! Can’t you take criticism?”

It may have been obvious to them that I was acting unusual, but I couldn’t see it. Nor could I see the confusion and suffering it was causing. Upstairs in the guest room, I was in my own world, fixated on their poor treatment of me and the gross incompetence of the American railway system.

As June arrived, I settled into my new routine: a never-ending parade of doctors’ appointments even as I continued to work full-time. At the office, I found the minor shortcomings of my employees very irritating. But instead of letting these things slide, as I normally would, I began to criticize them frequently.

Of course I find things irritating, I told myself. I’m tired of being sick. I’m tired of my rash. I’m tired of everything.

On the day of a physical-therapy appointment, I didn’t feel like going. I loathed the idea of another hospital, another treatment. But I’m a woman of my word, so rather than cancel at the last minute, I went.

I know our local hospital well. But that day, as I pulled into the parking-garage complex, I wondered if I was in the right place. Everything looked totally unfamiliar. I didn’t remember the layout.

Had they changed it?

Inside, the hospital looked different, too. I asked several people for directions, but no matter how much they tried to help, I couldn’t find the PT department. When I finally did, I was seething.

I took a seat in the waiting area, only to find myself across from a little boy who was coughing and crying. Why on earth would they let a sick kid into this room? I’m very ill. I can’t be around someone like him!

As he continued to cry, my loathing increased.

He’s going to infect me!

I hated the little boy. I hated his father. I hated this place.

My torment continued for a long while until, at last, a woman in scrubs entered the waiting room and called my name.

Such a strained, dishonest smile, I thought. What is she up to? I’d better keep a close eye on her.

Her name was Theresa. She told me I had waited too long to see her about lymphedema, a condition affecting my arm.

“You need a series of regular visits,” she insisted. “And you have to stop arguing with me.”

“A series of visits?” I started to laugh. “I have no time for such bullshit.”

I stood up and shot her a withering look, then wheeled around and stomped out the door into the hallway. “What kind of nonsense was that?” I said aloud as I left.

It was difficult at first to pinpoint the changes in my behavior because they’d come on slowly. My family’s attention, as you’d expect, was on the cancer. Besides, I hadn’t suddenly become someone else. Rather, some of my normal traits and behaviors had become exaggerated and distorted, as if I’d been turning into a caricature of myself. I had always been very active, but now I was rushing about frantically. I had no time for anything—not even for the things I really enjoyed, like talking to my children and my sister on the phone. I would cut them off mid-sentence, running somewhere to do something of great importance, though what exactly I couldn’t say.

I became more disinhibited. I stopped pulling down the blinds in the bathroom window at home when showering. It was too much work—and why would I block a nice view of the park?

My family began to tiptoe around me. Out of earshot, they would share their concerns. I wasn’t the same woman they’d always known, they agreed. But my actions hadn’t yet become so bizarre that it set off alarms. So all the while I was losing my grasp on reality, oblivious to the tumors wreaking havoc in my brain, the awful behavior caused by the same thing continued unchecked.

One hot and humid day in June, I headed to work in the early morning. By late afternoon, I was exhausted. I looked outside and saw dark clouds gathering over the NIMH campus. It was going to pour.

I bolted to the multilevel garage where I always park and headed to the spot I always use. But I didn’t see my RAV4.

That’s weird. I don’t remember having to park somewhere new today.

I walked the aisles, my Toyota nowhere to be found.

Someone stole my car!

Or maybe I just—I don’t know. Maybe I parked somewhere new and don’t recall it?

I reached into my purse for the key. I pressed the alarm button and heard a beep. It was coming from far off. I walked toward the sound, pressing the button from time to time to make another beep, then another.

What is happening? It makes no sense at all.

I retraced my steps and tried the same thing over and over: press, beep, nothing.

I saw a woman walking in my direction. “Can you help me find my car?” I asked.

She looked surprised but said she would try. She took my key and pressed the button, and we heard the beep. “It must be halfway up on the higher floor,” she said. “Look up there, through the gap between the floors.”

There, in the opening she was pointing to, I saw my Toyota on the ramp. But my confusion only grew when I climbed in. I’d been driving this car for three years, yet when I tried to fasten my seat belt, I couldn’t seem to find it. Instead, my outstretched hand dangled outside the door, hitting nothing but air.

Why am I having so much trouble with everything I try to do?

I looked around and noticed that my door was wide open. That was strange. But I couldn’t recall what that had to do with the missing seat belt. I sat for a while and then, annoyed, slammed the door with a bang. With that noise, my world returned to normal. Like magic. I slid my right hand across the inside of the closed door and easily located the seat belt.

Finally!

I started the engine and tried to back out. But suddenly I was stuck. Something was holding the car in place. I pushed harder on the gas pedal and heard a ghastly screeching sound of metal scraping something hard. I hit the brakes and looked to my left. Somehow, I was partially wedged under a small truck parked next to me.

My grandson looked at me as if he were about to cry. ‘You’re so mean!’ he said.

I tried to drive forward—the screeching intensified. I put the car in reverse, and the same thing happened. In desperation, I pressed really hard on the gas pedal. There was a terrifying noise of smashing and screeching and breaking objects, but I ignored all of it and finally freed myself from the trap.

As I pulled away, I saw that my car’s left side was dented. Was the truck damaged? I didn’t care. I simply drove away.

Although the exit driveway was narrow and slightly curved, it had never given me any trouble. I’d passed easily through it hundreds of times. When I reached it that day, though, it seemed much narrower, almost unrecognizable. I drove slowly, trying to squeeze through it. But I could not fit.

What are they doing with these driveways? Changing everything, constant construction on this stupid campus! Why did they alter the exit?

I heard loud scratching and a bang as I ran over a high curb.

The parking attendant ran out of his booth. “Lady, what are you doing?” he shouted.

“What do you think?” I muttered, increasingly irritated. “I’m just trying to get out of here!”

By mid-June, I had completed the immunotherapy and was excited. I felt certain nothing was wrong.

This wasn’t just wishful thinking or extreme denial; my worldview made perfect sense to me. I still saw myself as a scientist—a master of the rational—and was in fact still working hard on other people’s brains.

One day, though, when I was acting particularly strange, my family took me to the emergency room at Georgetown.

Dr. Atkins came into the hospital room looking devastated, as if he had failed me.

My poor doctor. He doesn’t understand—I’m fine!

In fact, I was the opposite of fine. Deep inside my brain, a full-scale war had erupted. The tumors that had been radiated were shedding dead cells and creating waste and dead tissue. Throughout my brain, the tissues were inflamed and swollen from the metastasis and the double assault of radiation and immunotherapy. What’s more, I had new tumors—more than a dozen. My blood-brain barrier, which normally prevents circulating toxins from entering the brain, had become disrupted by these new tumors as well as the treatment and was leaking fluid. The fluids were pooling in my brain, irritating the tissue and causing it to swell.

The largest of the new tumors was the size of an almond. It was in my brain’s frontal lobe. That’s the very spot that I knew from my animal experiments to be so crucial to directing everything that made me human—my ability to think and remember, to express emotion, to understand language.

Not that I could see what had happened to me, though. At that time, only my family and doctors were able to comprehend fully that it was the swelling and the location of the tumors that had caused me to behave like mentally ill patients whose brains I had studied. I was still incredibly sick. Though I would eventually recover, it would take a while to understand where my unusual odyssey had taken me: into insanity and back.

I’m a rare case. According to psychiatrists and neurologists, it’s highly unusual for someone with such serious brain malfunction to be successfully treated and return from such shadowy mental impairment. Most people with as many brain tumors as I had simply don’t get better.

As a scientist, I’m aware of how lucky I am. The underlying causes of mental illness are rarely as clear as metastatic brain cancer. Yet I feel I have come to understand what many of the patients I study go through—the fear and confusion of living in a world that doesn’t make sense, a world in which the past is forgotten and the future is utterly unpredictable.

My brain will never be as it was before. It has been injured by tumors, shot through with radiation, assaulted with drugs. It is scarred, figuratively and literally. And because my brain is different, I’m not exactly the same person I was before the illness. But oddly, I feel completely myself.

From time to time, I would make stupid jokes, pretending to lose my mind, faking that I didn’t know where I was. Mirek didn’t laugh. It was cruel, I realized, and I stopped doing it. After all, I’m the only one who didn’t witness what happened. I’m the one—in a way—who suffered least.

Adapted from “The Neuroscientist Who Lost Her Mind: My Tale of Madness and Recovery” by Barbara K. Lipska with Elaine McArdle, to be published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on April 3. Copyright © 2018. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

This article appears in the April 2018 issue of Washingtonian.