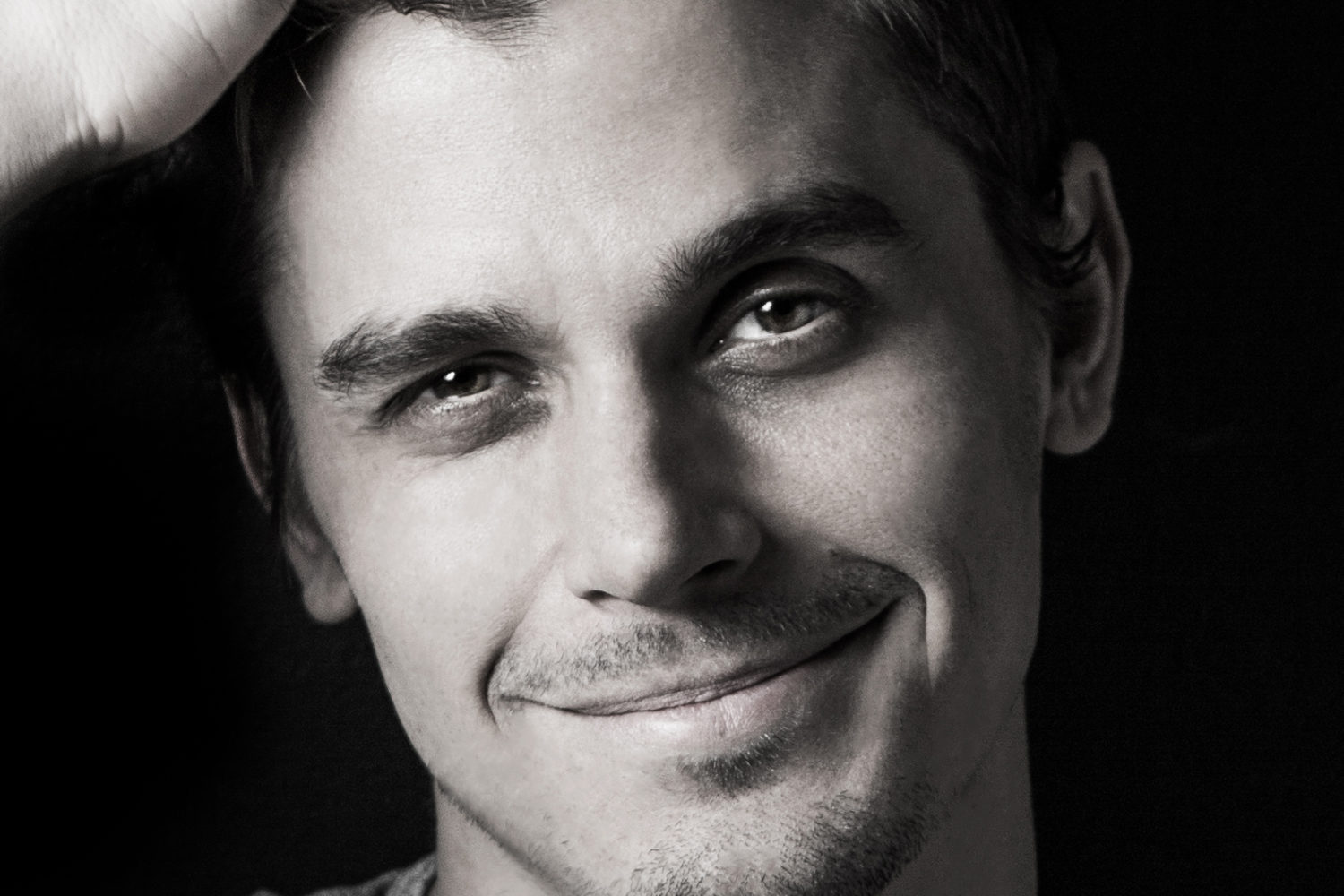

During his senior year at Georgetown University, Mackenzie Copley noticed something odd while volunteering at a doctor’s office: it turned away around 20 individuals a day who came in for HIV screening. When Copley asked why, he was told it was because the clinic was a for-profit, private company. “That really bothered me,” he says. “So 21-year-old, impatient me started a nonprofit.”

DC has the highest rate of HIV infection in the country, according to the most recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As he began researching how a nonprofit that offers free HIV screening might look, Copley hit one major snag—the economic and physics major had no medical background. So he turned to his friend, David Schaffer, who was in medical school at the University of North Carolina. In May 2016, they founded One Tent Health, a nonprofit that aims to increase accessibility to HIV screening and prevention in DC with free, pop-up screenings out of a ten-by-ten canvas tent.

How does a pop-up HIV screening tent work? The team—Copley, Schaffer, volunteers, and interns—sets up a tent in the parking lots of grocery and convenience stores in the District’s highest-risk neighborhoods. The areas are carefully selected using prevalence rate and whether there’s already a free clinic there in order to avoid duplicating efforts. Before their first screening in a Giant parking lot last October, “We were kind of wondering, are people gonna wanna stop while they get groceries?” says Schaffer. “Within minutes of setting up, we had people stopping by.”

The tent model is the lowest cost option available that they identified that still ensures privacy. “Instead of a $50,000 van, we have a $500 tent,” says Schaffer. One Tent receives screening kits at no cost from the DC Department of Health. Screenings take 60 seconds, and the whole process from walking into the tent to getting a result takes around 15 minutes, or less time than going to a clinic, says Copley, pointing out that access is a huge focus for One Tent. “One thing that we see a lot of in medical school and in the hospital is issues with access,” adds Schaffer. “We’re breaking down a lot of those barriers in a pretty simple way.”

Volunteers make up a huge part of One Tent, and currently, the organization has around 225, mostly from local colleges. Every volunteer undergoes confidentiality training, and the team follows HIPAA standards for data security. In the instance the individual needs further treatment, One Tent provides what it calls “linkage to care” through a formal partnership with Whitman-Walker Health, which has agreed to see individuals the same day, without an appointment.

One Tent also offers PrEP Navigation services, in which the team asks people if they’ve heard of PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), a daily oral pill that’s been shown to dramatically reduce the risk of HIV infection in those who don’t already have HIV, according to the CDC. The team conducts “warm hand-offs” to Whitman-Walker Health for those who want to learn more about PrEP or receive a prescription.

So far, One Tent has screened 177 individuals at ten events. Their goal is to conduct 4,000 screenings annually, and this fall, One Tent will expand into Prince George’s County. “We’re a group of young DC kids trying to do something good for the city,” says Copley. “We just want to be a small part of the greater DC solution.”