In the 1980s, Bob Clarke studied at Queen’s University Belfast amid the 30-year conflict that engulfed parts of his native Northern Ireland. “If you could get out, it was a good option,” Clarke says. So after earning his PhD in biochemistry, he got out, landing first at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda and then, starting in 1989, at Georgetown University.

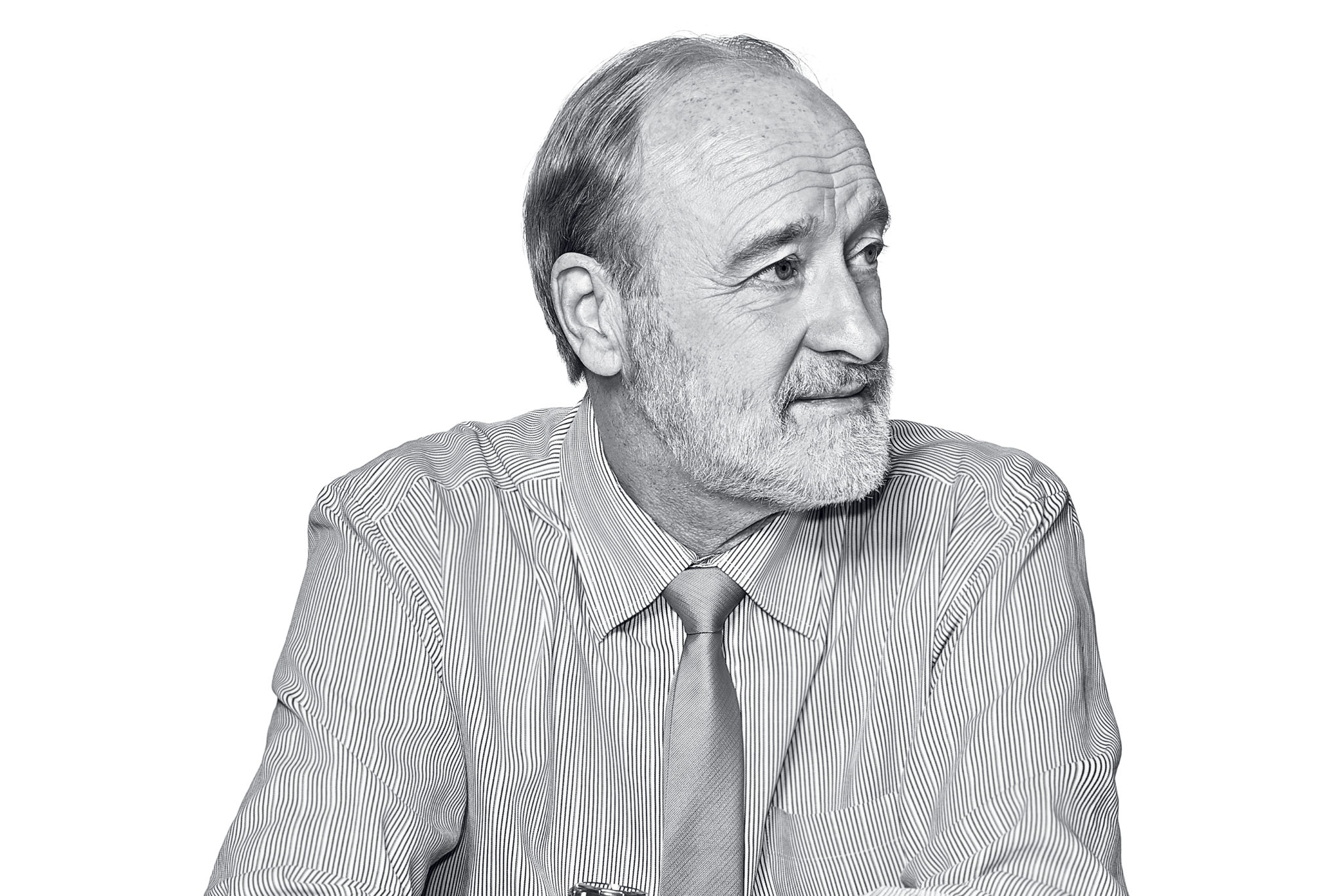

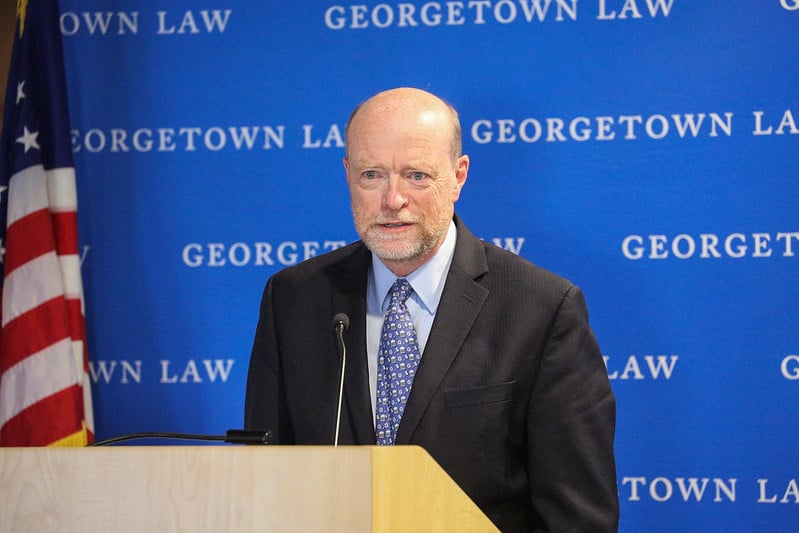

Today, Clarke is Georgetown University Medical Center’s dean for research, overseeing a range of significant medical initiatives. He’s also a professor of oncology and codirector of the breast-cancer program at Georgetown’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

In his dark, wood-paneled campus office, the blinds drawn to dim the late-afternoon sun peeking in over stacks of papers, the Rockville resident—wearing a tie bearing the crest of the Royal Society of Chemistry, where he’s a fellow—discussed his work.

How exactly did you get from studying in Belfast to working in DC?

I went to a conference in Rotterdam. One evening, there was a dinner cruise. I was sitting at a table, and one of the other attendees says, “So what are you going to do when you finish graduate school?” I said, “I thought it’d be nice to go to the States. NIH is really good. I’ve been reading papers in my thesis work by this [oncologist] called Marc Lippman . . . .” Before I could finish the sentence, he stood up and shouted, “Marc, Marc, there’s a guy here that wants to talk to you!” I went over and talked to him, and I got an offer within a week. I worked as a postdoc at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, and then Marc was recruited to Georgetown. I ended up here, and I’m still here.

So what are you up to? Georgetown has quite a bit of research happening for an institution its size. One notable area is immunotherapy for advanced melanoma.

Immunotherapy is just blowing the walls off cancer research. The potential really is remarkable. Where it will continue to be remarkable and where it will not be quite as good as we’d hoped is difficult to tell, but some of the results we’re getting in the clinics here, particularly Mike Atkins’s work—seeing patients survive who would have had months to live—goes beyond calling it life-changing. It’s death-changing.

What about breast cancer? Georgetown researchers have been investigating a new class of drugs, called CDK inhibitors, that might help some women.

The ones we now have the most trouble with are the 10 to 15 percent who don’t respond to other treatments, and we still don’t have good targeted therapy for them. I mean, it sounds like it’s only 10 to 15 percent of breast cancers, but it’s 10 to 15 percent of a quarter of a million new cases every year.

Is cancer really curable? Do you think it’s realistic to be saying we’re working toward a cure?

Oh, I think if we’re not working toward a cure, what the heck are we doing? It gets to how you define a cure. If every woman who had breast cancer lived long enough to die of old age but still had breast cancer, we’d chalk that up as a cure. We’d just redefine “cure” as “dying of something else, not of breast cancer.” And I’m okay with that.

Would I like it to be a situation where anyone who got that diagnosis could come in and get treated and never have to think about it again for the rest of their lives? You bet. But there are other things. Even when you can’t cure something, if you can give someone the time to watch their kids grow up and graduate from college and marry and have grandchildren, you’ve given that person a life. It may not be as long a life, but you’ve given that person life.

Georgetown has historically been involved in some big breakthroughs, such as the HPV vaccine and the artificial heart valve. Have you ever had—as with the famous story of Henrietta Lacks—some small discovery that ended up transforming your research later on?

I think we have those all the time. We just misinterpret them most of the time. You know, science is done by the scientific method, which basically requires you to create a hypothesis that you can test. You go into these experiments usually with the arrogant, hubristic thought that you’re probably right. Then nature turns around and pokes you in the eye.

That’s another wonderful thing about science: being proven wrong. It grounds you. So does talking to the patients. I remember one conversation where I said, “Did you see that recent study that says there might be ways to reduce your hair loss during chemotherapy?” I was thinking she’s going to be really interested in this. She looked at me and said, “No. I don’t care if I lose my hair. I care if I live or die.” Everyone has a different perspective.

Last year, President Trump’s proposed budget threatened to slash NIH’s budget, which is a big source of your research funding. It didn’t happen, of course, but what would it mean for your research if it did?

It would’ve shut us down.

Completely?

[Nods.] The challenges that we still face are: Cancer is smart, it’s not the same in every woman, and the questions that we ask are not easy or we would have solved them a long time ago. But the tools we have are unbelievable compared to when I got off the plane in nineteen-eighty-whatever-it-

How so?

Technology has changed. You would expect that as the technologies get better and our ability to move more quickly improves, the resources to allow us to do that would follow suit. It’s gone in the opposite direction. As it continues to be more expensive to do more technology-driven, insightful research, the cost continues to go up and our ability to get the funding goes down. Every grant that’s submitted, on average, for an individual project in cancer is looking at about a 90-percent failure rate in terms of getting funded. You don’t get to ask the question if you don’t get the funding.

What makes Washington different as a medical-research hub?

Proximity to power, to government, to decision-making that exists on an international scale. Most other countries in the world are represented here. It’s a very diverse community that brings into it diversity of culture and diversity of thought. You’ve got places of inquiry and experience that are world-class. You’ve got representatives from some of the most influential nongovernmental agencies, like the World Health Organization. There are ways in which you can begin to discover something here and have impact way beyond DC. You can interact with representatives of agencies who can take that knowledge. This is just an amazing city for being able to do that type of networking on that scale.

It’s a privilege to be working in a prestigious institution in one of the most powerful and influential cities in the world.

Of course, you also have to unwind from all of this. Do you have a favorite Georgetown pub?

Oh, you can’t not like the Tombs, in [the basement of] 1789. It’s so lively, and it’s full of students. That’s one nice thing about being here: You’re surrounded by young people who are energetic and inquisitive and pushing boundaries. You never feel like you’re getting old—despite the fact that you are.

This article appeared in the June 2018 issue of Washingtonian.