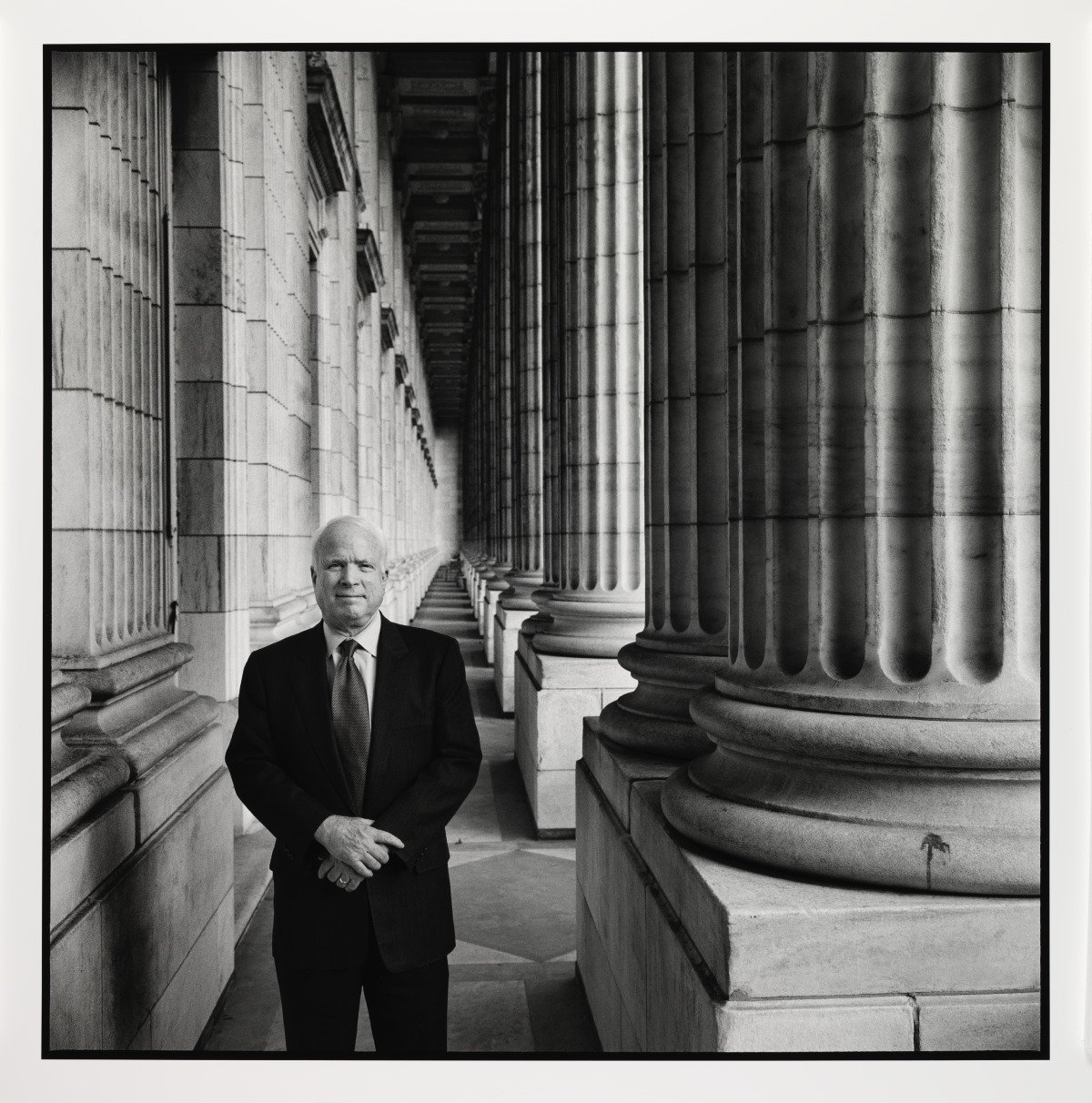

John McCain died on Saturday, August 25. The National Portrait Gallery had a black-and-white Steve Pyke portrait of him on its “In Memoriam” wall by 11:30 AM on the following Monday.

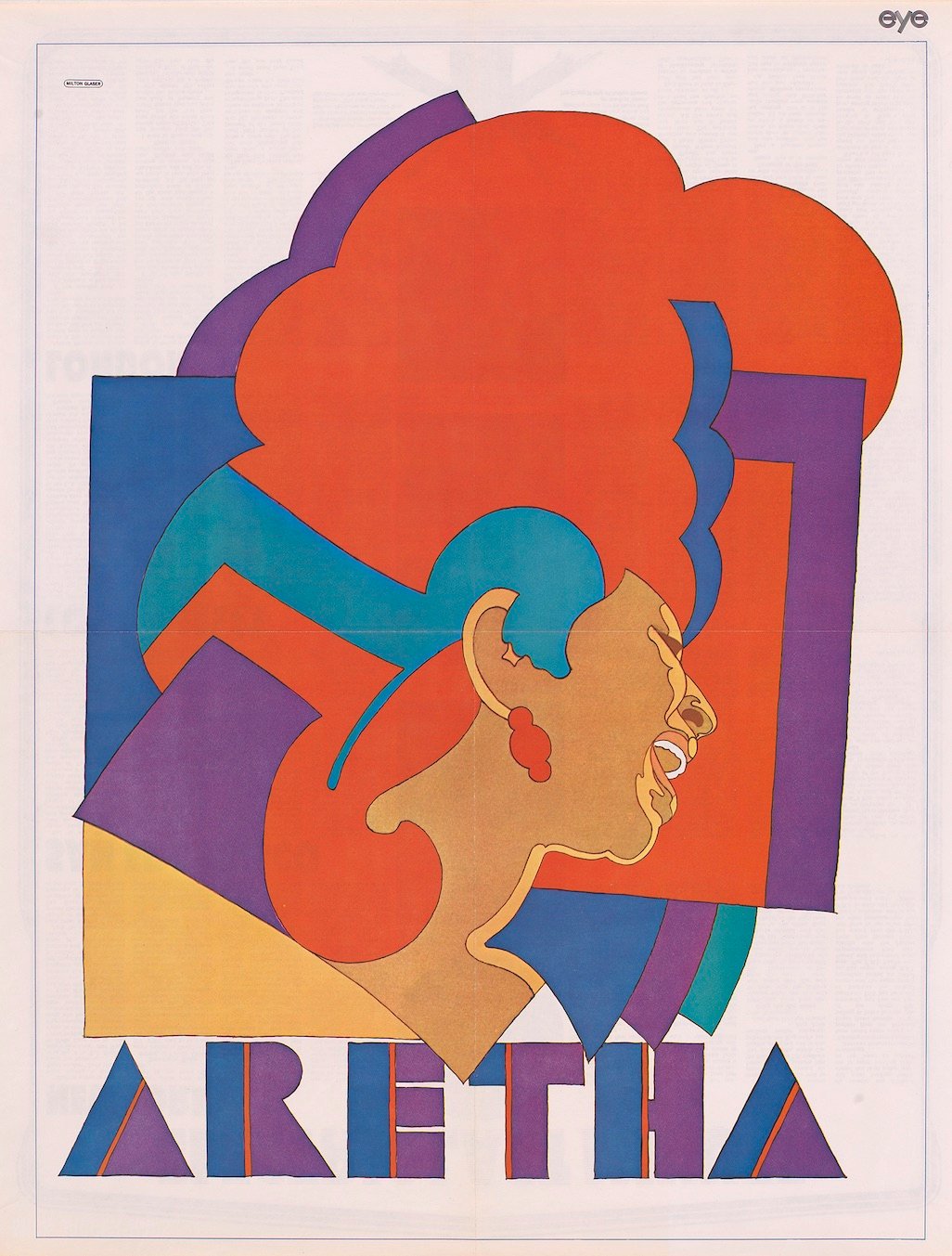

In museum terms, this is lightning speed: The concept-to-wall process usually takes three to four years. But over the past 12 years the Portrait Gallery has developed a rapid response team that’s extremely good at memorializing the deaths of high-profile people. McCain’s portrait went up nine days after the Portrait Gallery got Milton Glaser’s 1968 portrait of Aretha Franklin on the wall the day after her death.

“It’s an interesting snapshot of the exhibit process in miniature,” says Alex Cooper, the head of exhibit technology at the gallery. “All the teams that are involved in full-blown exhibitions are involved.”

The Portrait Gallery can turn around these tributes thanks to its immense permanent collection. But choosing the right portrait to represent a key individual in American history is not easy. Neither is locating one that’s in storage close enough to the museum to be matted, framed, and installed quickly.

Cooper walks through the process: “When we learn that someone has passed away, or is very ill, these conversations start, and you start to see them show up in your inbox around 8 or 9 o’clock. So the coordination—and I’m at the very end of the line—preceding me is exhibit design decisions, cutting vinyl, matting, framing, getting objects from our collection, storage, other designers, our curatorial staff, and PR—these are all the conversations we have when we plan exhibits.” Donors also often have to sign off on the display.

The McCain portrait will come down on September 23, says Claire Kelly, the museum’s head of exhibitions. Most “In Memoriam” installations stay on the wall for anywhere between 2-4 weeks.

There’s only so much space on that wall, which means that sometimes the curators and historians in the group have to make difficult decisions. When two significant deaths occur, “it is kind of the call of our curators and historians,” Kelly says. “With Neil Simon, we did a blog to recognize him at the same time the McCain was on the wall.”

When the wall isn’t being taken over by a portrait tribute, it shares the space with three other themes: “Celebrate,” “In Remembrance,” and “Recognize”. “Celebrate” and “In Remembrance” portraits are usually used to commemorate a historical event, while “Recognize” is chosen by public vote through the Gallery’s Facebook page to highlight different parts of the collection.

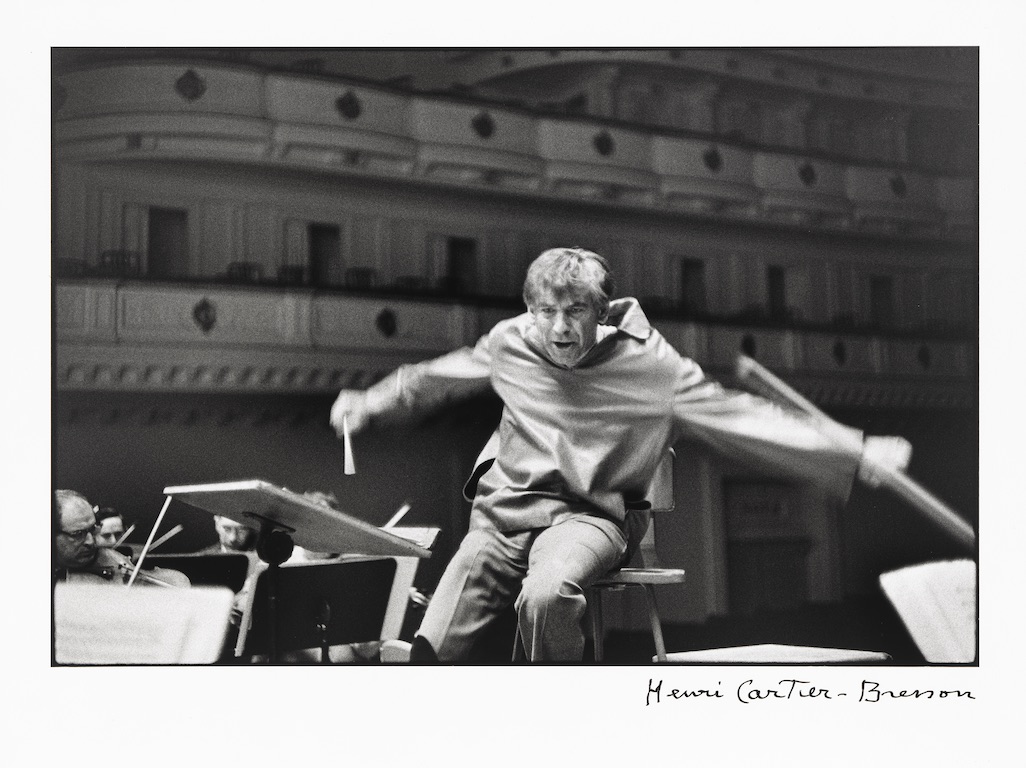

“In Memoriam” takes precedence over the others. McCain’s death interrupted the celebration of the late composer Leonard Bernstein’s centennial four days after his portrait went up, a move that has garnered criticism from music lovers.

“It’s really difficult,” Kelly says. “We only have one wall.”

Sometimes it’s an emotional decision as well. With the Prince memorial, the powerful nature of a visual tribute served as a “pilgrimage” point of sorts. Cooper remembers watching visitors gather around the portrait immediately after the news of his passing.

“We present American history and biography in visual terms. Only we can do what we do,” Cooper says. “This is biography and culture right now, right here.”