On Sunday, the National Gallery of Art will open a new exhibit dedicated to Gordon Parks, a famed photographer, musician, poet, and filmmaker who dedicated much of his career to documenting African-American life during Jim Crow, segregation, into the Civil Rights movement and beyond. Parks’ work ranged from directing Shaft to composing piano pieces by ear, without knowing how to formally read or write music.

“Parks was a renaissance man, but he had to start somewhere,” says Philip Brookman, consulting curator at the National Gallery of Art. “That’s what this show is about—his beginning.” In just a decade, Parks went from a self-taught portrait photographer and photojournalist in Saint Paul, Chicago, and DC to a celebrated professional working in New York for Ebony and Glamour. In 1949, Parks became the first black photographer at Life magazine.

The exhibit is divided into five sections, detailing his transition from a studio photographer to his work for the Farm Security Administration and the Office of War Information, to his photos for a Standard Oil Company PR campaign; and, finally, his prominent photography for major fashion and lifestyle magazines. His music, which often accompanied his films, will be performed in the gallery’s East Building during the opening. Here, we look at some of the shots from his time in the District, which was fertile ground for improving his craft.

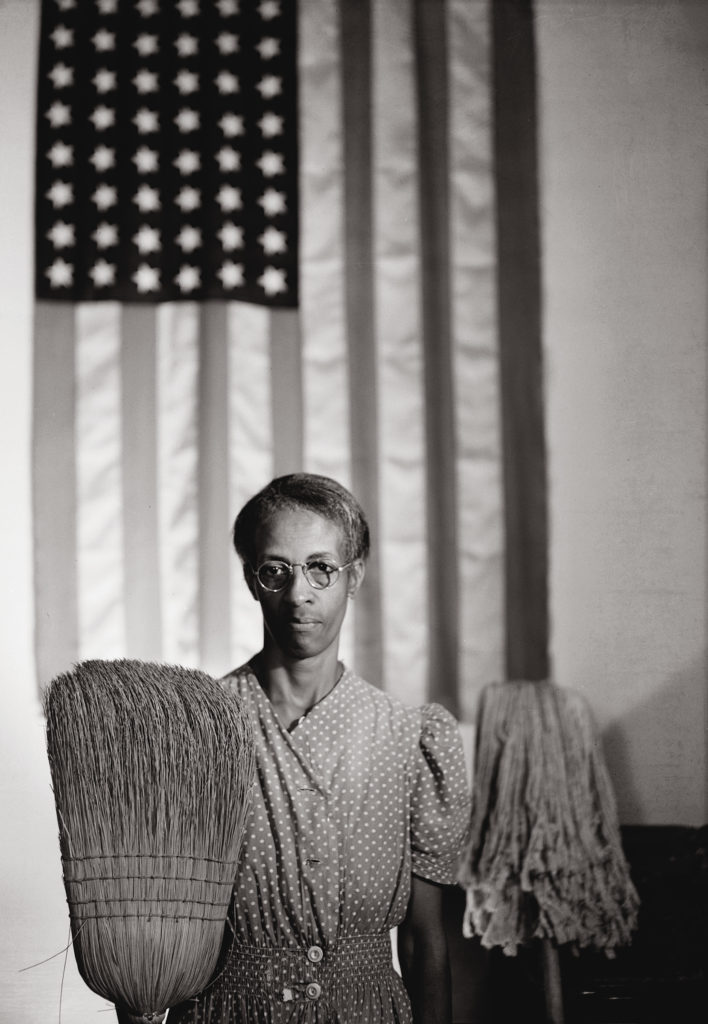

Parks’s American Gothic-like portrait of Ella Watson is perhaps his most recognizable, and it is front and center at the exhibit. Watson was a government charwoman for 26 years and cleaned the office buildings at night—including the Farm Security Administration building pictured here. On just $1,080 a year, she took care of five children during as a single parent.

With Watson, Parks was interested in capturing her beyond her job. This photo depicts four generations of her extended family in her 11th Street, NW apartment. In his application for the prestigious Rosenwald Fellowship, Parks wrote that he sought to portray “the Negro in his intellectual, professional, educational, social, farm, and urban life.” In April 1942, Parks was awarded the first fellowship given to a photographer.

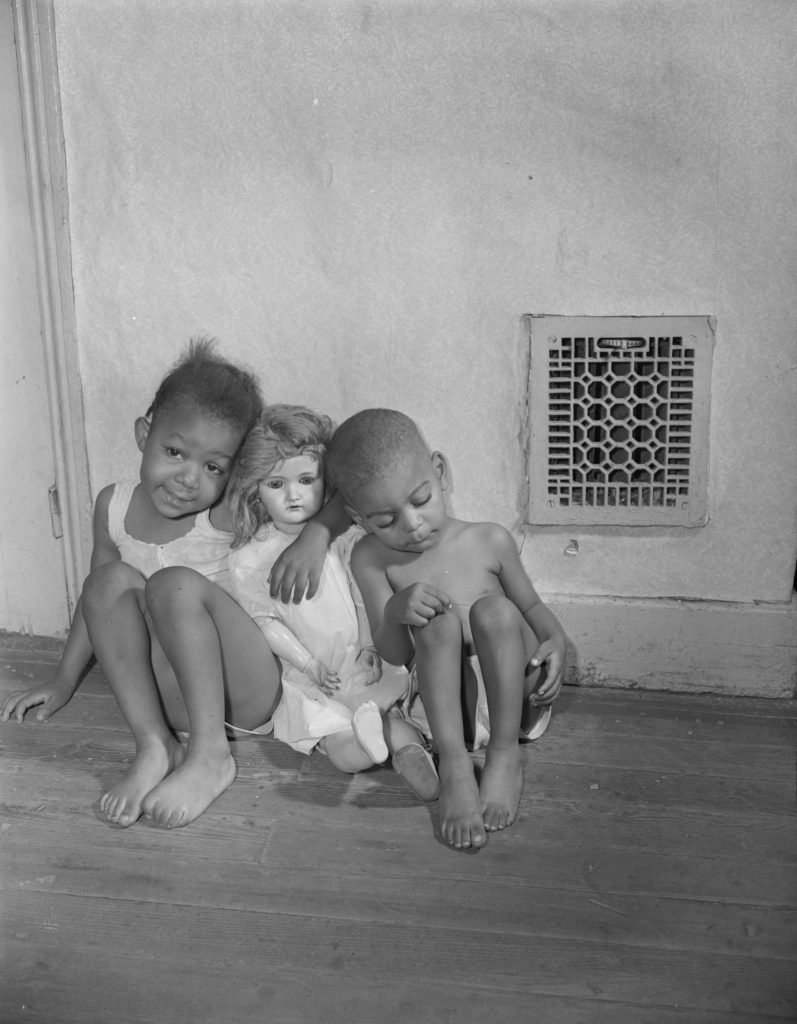

In his photo series about Watson’s life, such as this one of her grandchildren, Parks used lights, walls, windows, and mirrors to create layers of context. Parks struggled as an artist working odd jobs before finding success and spent his first winter in Minnesota homeless, so, in many ways, he related to the subjects in his photographs.

This photo of a government worker in her bedroom with a portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt on the wall uses a technique Parks learned from other Farm Security Administration photographers: using reflections to convey a message. “He wanted to use his camera as a weapon against ugly racism in this country and in the world,” says Brookman. “He knew to do that, he had to be able to convey a sense of how it feels to be black and going to a segregated school, and other experiences. Parks learned through a series of moves, as you’ll see in the show, how to create a narrative that would relate to social issues. He became a social documentary photographer.”

Parks understood the relevance of spirituality in the lives of black Washingtonians. Here, he captured a service at the Church of God in Christ. He also spent time with Ella Watson at Verbycke Spiritual Church, where she frequently worshipped.

Parks documented conditions on the home front during World War II, including Anacostia’s Frederick Douglass Dwellings public housing, workers at the Fulton Fish Market in New York, and the training in Michigan of the Tuskegee Airman, the first black military aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps. Here, he photographs a boy standing in the doorway of his home on Seaton Rd., NW. His leg was cut off by a streetcar while he was playing.

When Parks arrived in DC in May 1942, he immediately sought to make portraits of those who would otherwise be forgotten. That included his neighbors on Lamont St., NW near Howard University, the people he met near the U Street Corridor, and those living in the shadow of the Capitol, many of whom resided in housing projects with no indoor plumbing. Here, Parks photographs a young girl living in Capitol Hill.

“Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Work 1940-1950” will run at the National Gallery of Art November 4, 2018 — February 18, 2019.