Hayley Solak has never been on government assistance before. “This was my first shutdown,” says Solak, an IT contractor for the Department of Agriculture. It was the evening of the 18th day of the shutdown, and the 14th day Solak has gone without pay as she stood in front of the White House, clad in a dark nylon jacket and blue jeans, looking on at a gathering protest on Pennsylvania Avenue. “I really didn’t think it was going to last this long. I had no idea if our contracts had a failsafe in place. I thought they did.”

They didn’t. On December 24, her company received a “stop work” order. Solak and her colleagues pored over a company email, which described two options: Burn through their paid vacation time and receive a paycheck or take an indefinite leave without pay. About that time, Solak heard from her grandmother, who offered to send cash—but “she’s 88,” laughs Solak, “and I would rather not take her money.” Expenses for Solak, who lives in Adams Morgan, are a little more than $2,000 each month.

So, on Monday, at age 30, Solak applied for unemployment insurance benefits for the first time. She’s hoping to receive the maximum weekly check one can receive in the United States: $425, though “that’s not going to be enough,” she says. She’ll find out on Friday what she’s eligible for.

As the shutdown approaches its fourth week, regional economists have pointed to the skyrocketing number of Washington area residents who are applying for unemployment benefits. In the past week, budget specialists in the DC government reported growing numbers of federal workers claiming unemployment benefits: First 300, then 700, then 1,700. It’s now estimated at 5,431, including 4,429 federal workers and an estimated 1,002 federal contractors. The number already equals 15 percent of the typical benefits caseload in a single year, according to figures provided by the Department of Employment Services, where District employees have been working overtime to manage the deluge of incoming calls and applications.

In Maryland, federal workers have filed more than 1,300 claims, not counting contractors. And in Virginia, “There has been definitely been an increase in volume of activity,” says Bill Walton, who leads the unemployment insurance program at the Virginia Employment Commission. Virginia has seen 368 claims so far, Walton said, “with every indication that more are coming.”

If the shutdown continues to Friday, it will be the longest in American history. Also on Friday, a new wave of federal workers will officially miss their first paycheck, and the number of unemployment claims is likely to balloon. “We got a message yesterday, which included a letter to give to the unemployment office,” says Becca, a lawyer at the Securities and Exchange Commission, who gave only her first name to discuss her personal financial straits. Because her Friday paycheck still withholds benefits and taxes, “I expect to get nothing,” she says.

But the economic plight is hardly limited to government workers like Becca and contractors like Solak. Federal workers and contractors are large enough contributors to the economy that their abrupt absence from the market can spur an increase in all unemployment claims nationwide.

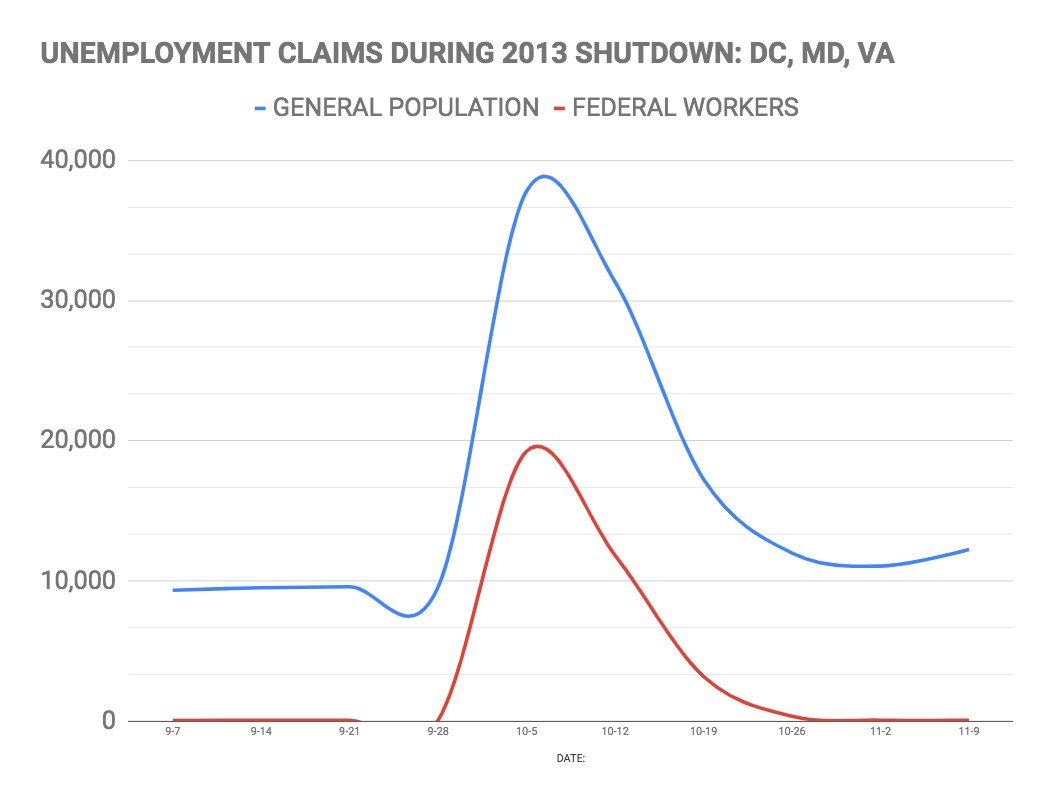

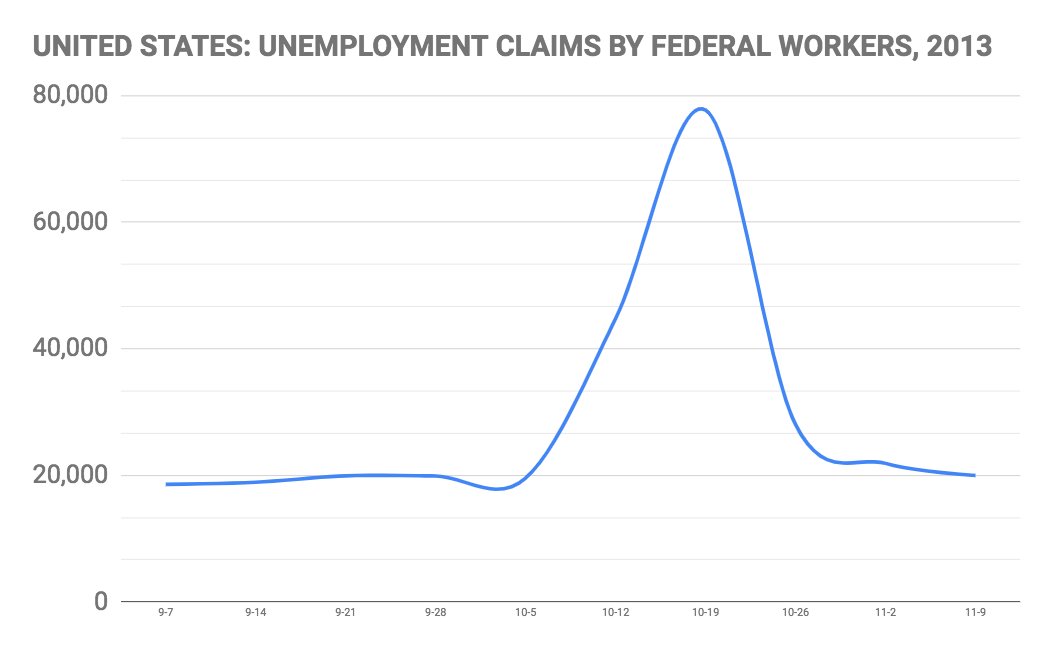

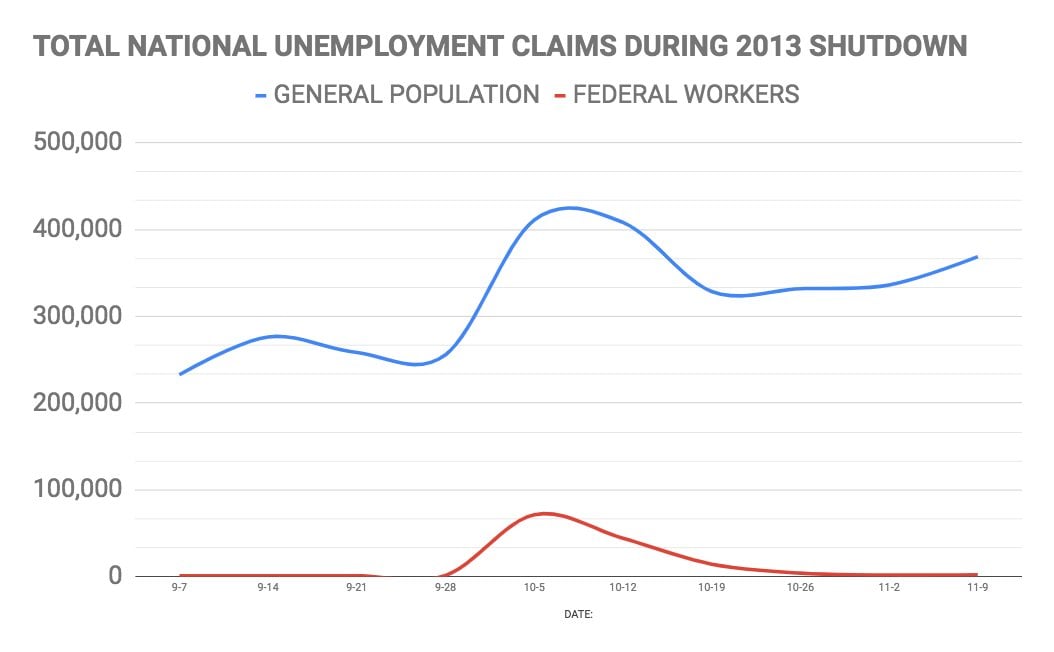

According to figures from the Department of Labor, more than 130,000 federal workers were forced to claim unemployment benefits during the last major shutdown in October 2013. The uptick in private sector workers was nearly double that when compared to the September average. Stephen Fuller, a professor at George Mason University who closely studies the area’s economy, says this rise is partly explained by “collateral services” such as the janitors who service closed federal buildings, the staff at the McDonalds inside the Air and Space Museum, and people at food trucks or restaurants that specifically cater to federal workers or buildings.

“Then there’s the ‘induced effect,’” Fuller says. “Those are the workers tied to the spending of the payroll that’s been lost. It could be a grocery store person, or a limousine driver—somebody further away from the obvious.”

At the shutdown’s end in 2013, claims indexed to government employees snapped back to near-zero. But private sector claims took weeks to fall to their pre-shutdown numbers. “The non-federal workforce impact continues well beyond the shutdown, and appears to accelerate,” Fuller wrote in an email. “This lag in workforce impact…may not be appreciated.”

Federal workers are expected to receive back pay, alleviating some of the hardship. Contractors or private sector employees are not. And many losses simply can’t be made up: “Nobody eats two lunches tomorrow to make up for them,” says Fuller. “If this keeps going on for two weeks—certainly for a month—at some point it could put those people permanently out of business.”

“We’re hearing from companies every day that there’s more ‘stop work’ orders being issued,” says David Berteau, who represents government contractors through the DC-based Professional Services Council. “They’ve exhausted all possibilities, and are going to have to start laying people off.”

Unemployment benefits are just one of the reasons why it typically costs taxpayers more to shut down the government than to simply leave it open. If federal workers do eventually receive back pay, the law requires that they repay their unemployment benefits to the state. But Maryland, for instance, is still waiting to receive $215,000 in unemployment benefits for federal workers during the 2013 shutdown.

Another potential consequence: Contractors and federal employees giving up. Berteau says his fear is that people put out of work by the shutdown “will say, ‘To heck with public service, I’m going to go take another job.’ And then they won’t come back.”

Solak says she’s considering taking that advice, erasing government work from her future career plans. For now, though, she’s more concerned about her colleagues. “I’m in a better position than others,” she says. “There’s a woman on my team who’s a single mom. I don’t know what she’s going to do.”

For her own part, Solak says, “I’m just kind of floating in a cloud of uncertainty. I can’t plan for anything”—at least not on $425 a week.

Especially, she added, “when you don’t know how long it’s going to last.”