The Washington Post’s Style section celebrated its 50th anniversary on January 6. It has long been one of the paper’s signature brands, the vaunted home for some of its best writing and most popular bylines. It has also, as anyone who has worked for Style will tell you, always been dogged by accusations that it isn’t as good as it used to be. “We are certain that by the end of Style’s first week, someone complained that it was better on Monday and Tuesday,” TV critic Hank Stuever wrote on the occasion of the section’s 40th anniversary.

But what if the real issue with Style isn’t that it has gotten worse but rather that—at least in one important sense—it no longer exists? Oh, sure, Style is there in print subscribers’ newspapers every morning, profiling Washington notables, riffing on pop culture, and diving into books, museums, and dance. But in terms of how the Post thinks about and produces its coverage of arts, culture, and media—and, crucially, how readers experience that coverage online—the traditional Style section of Sally Quinn and Henry Allen is, essentially, no more.

This state of affairs is mostly due to the Post’s longtime struggle to transfer the Style brand to the internet. That effort ended quietly in February 2014, when a major reorganization combined Style, Food, Weekend, Travel, the magazine, and other parts of the paper into a single Features section, overseen by features executive editor Liz Seymour. “They all operated independently,” Seymour says, explaining that the sections didn’t collaborate in sustained ways. “The rest of the newsroom was moving much faster digitally.”

Style still technically lives on as a department, overseen by deputy features editor David Malitz. But in practice, the print section is more of a compendium of stories that have already been published online by the Features department’s 85-person team. In December, for example, Food staffers Tim Carman and Maura Judkis led Style with a story on chef Mike Isabella’s downfall—a cross-department collaboration that would have been unthinkable in the old days.

The thing is, Style only ever made sense in print. Print products thrive by creating an intriguing mix of carefully curated stories that together form a cohesive experience: Here’s what’s in today’s section. But online, readers get content à la carte, eliminating that whole idea of a single, unified collection of items. What would it even mean to have a Style section on the internet? That was a question the Post could never quite figure out how to answer.

Visit the Post’s homepage and you’ll have a hard time finding a link to its most storied of sections. Articles are instead promoted under headings such as Lifestyle and Arts. There’s a logic to this: Online, where readers are just as apt to be in Kansas City—or Karachi—the word “style” is more likely to connote couture than to represent the groundbreaking section where you might find a Ben Terris profile, a shady review of Post Malone, or a fiery Margaret Sullivan column. (Confusingly, on the article page itself, some of those pieces are occasionally labeled Style, which inevitably leads to someone demanding to know why such a story is in the fashion section.)

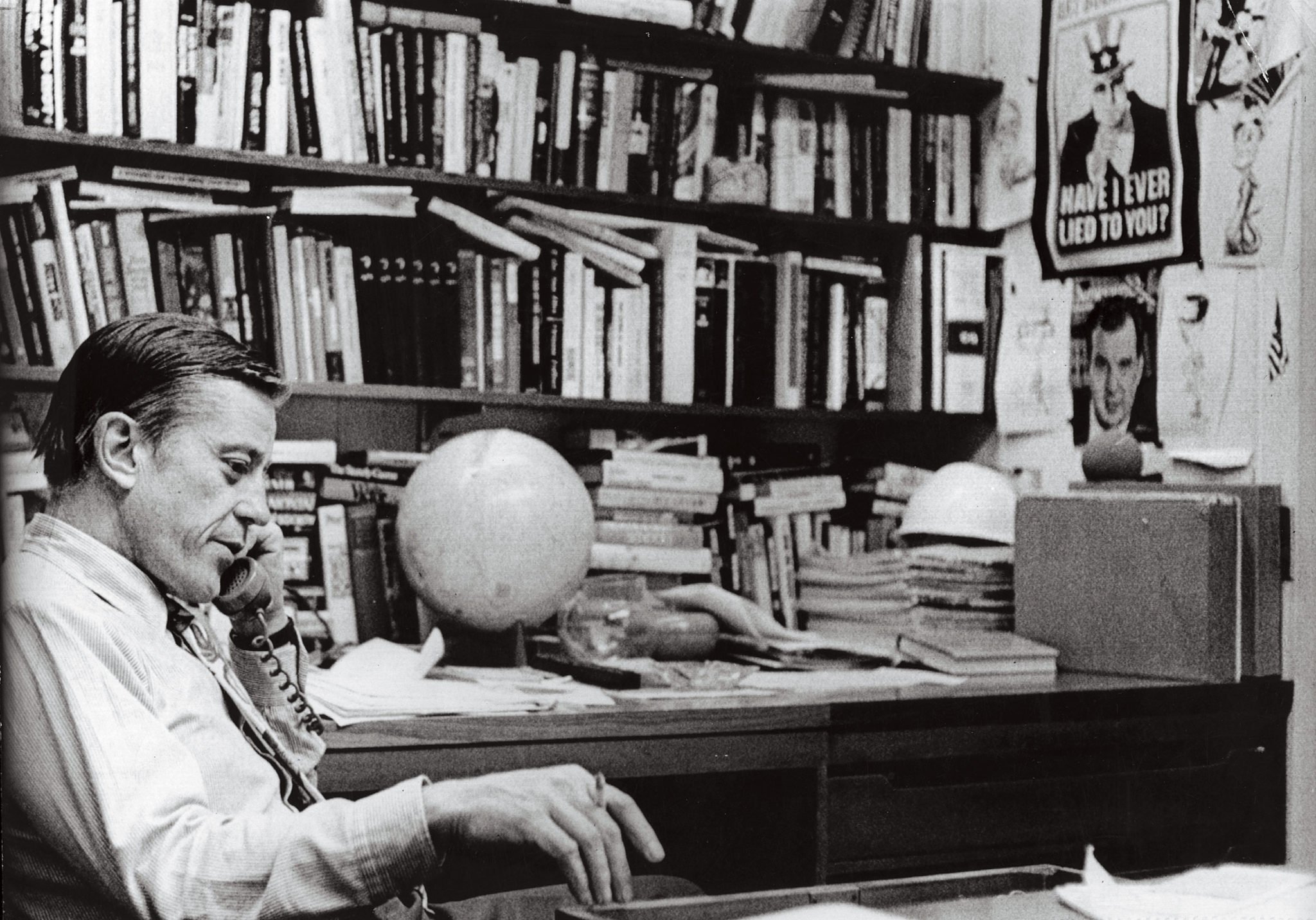

What those readers—and presumably many younger locals who have only ever engaged with the Post online—don’t realize is that Style has long been the scrappiest part of the paper, an alt-weekly with literary ambitions wedged into a daily newspaper. Ben Bradlee, who conceived the section in the late ’60s (with help from Dave Laventhol and Nicholas von Hoffman), was inspired by dissatisfaction with the paper’s For and About Women section and an infatuation with the New Journalism found at the time in magazines like Rolling Stone, Esquire, and New York. On its debut day, Style profiled Ruth Eisemann-Schier, the first woman on the FBI’s Most Wanted list. Reporter B.J. Phillips memorably described Schier, then on the run, as “a girl who never lacked masculine attention.”

Over the years, it became an artisanal powerhouse, with writers such as Tom Shales, Judy Bachrach, and Robin Givhan regularly delighting and enraging readers. It’s where Wil Haygood wrote about the White House butler who lived to see a black man become President. It’s where Judith Martin became Miss Manners. It’s where Sally Quinn turned party reporting into a place for Washington swells to hang themselves on their own quotes.

Then the internet came along. The Post’s hard-news sections crossed over relatively easily to the digital world, but Style was a puzzle. Initially, staffers pushed hard for a distinct digital presence that replicated what they were already doing in print. So what if the Style name didn’t mean anything to people outside the Beltway? The paper figured it could build a separate audience for Style, similar to what New York magazine’s Vulture ended up becoming.

It didn’t happen. Style was a “perfect print product that did not translate” to the web, says Jim Brady, the former executive editor of Washingtonpost.com. “The pieces did, but the package didn’t.” Editors who worked across the Potomac at the Post’s once-separate digital operation describe banging deep dents in their desks with their heads while trying to work with Style staffers hell-bent on keeping the bundle together.

It took the 2013 arrival of executive editor Marty Baron to puncture the torpor. He reportedly didn’t understand why, for instance, Style and Weekend reviewed the same films, a relic of the paper’s old siloed thinking. Jeff Bezos’s purchase of the Post in 2013 was a strong signal that digital-first thinking would be the future.

The big 2014 reorganization finally sent the message that Style would have to change its approach. Now the team is organized “by what we cover and not who we write for,” Seymour says, and Features columnists such as Monica Hesse often take up as much of the internet’s attention as the latest Trump scoop. The strategy seems to be paying off. While the name Style doesn’t have nearly the weight it once did, the Features department is thriving, and Style continues to add staff. It recently brought on Avi Selk as a general-assignment writer and is still looking for another one. More than 130 people applied for the openings, Seymour says, a testament to the lingering power of the brand. Even though, you know, it used to be better.

This article appears in the February 2019 issue of Washingtonian.

Correction: This article originally stated that Marty Baron arrived at the Post in 2012. That’s when the paper announced his hire. His first day was January 2, 2013.