The more Lisa-Marie Riggins spoke, the more flabbergasted Frank Fahrenkopf became. It was November 2016, and the two were having lunch at the City Club on 13th Street with Lisa-Marie’s husband, John, the Washington Redskins’ star running back in the 1970s and ’80s.

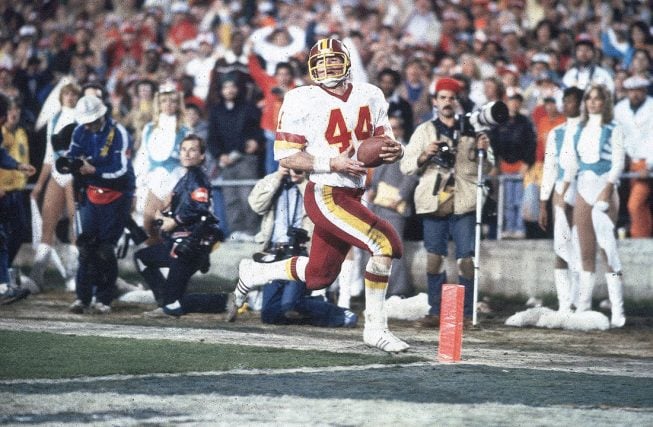

Fahrenkopf had chaired the Republican National Committee in the 1980s. Like many prominent Washingtonians of the Reagan era, he often was a guest in former Redskins owner Jack Kent Cooke’s luxury box at RFK Stadium—back when the team was winning Super Bowls and when a breakaway run by “Riggo” would cause the stadium’s bleacher seats to bounce up and down. “When that place started to rock,” Fahrenkopf says, “it would literally move!”

He’d been thrilled to get Lisa-Marie’s lunch invitation. But she and John didn’t want to reminisce about gauzy past glories, such as the time John shed Miami Dolphins defender Don McNeal like a wet overcoat while rumbling 43 yards to score the go-ahead touchdown in Super Bowl XVII. Instead, the couple had a case to make.

Lisa-Marie, an attorney who’s been told (more than once) that she looks like actress Heather Locklear, laid out the facts as if she were arguing a case in court. Too many older NFL retirees were in trouble, she explained. Their brains were battered, their bodies breaking down. They were struggling to support themselves and their families. They needed help. And they needed money.

These men had helped build the league, which in 2017 generated $14 billion in revenue. They had made it possible for today’s players to receive multimillion-dollar salaries, generous pensions, and a host of other retirement benefits. Yet almost none of them had gotten rich playing football, and now they were being left behind, Lisa-Marie said. Their pensions, dating from the contracts of a previous era, were relatively puny—in some cases, totaling less than $20,000 a year. Did that seem fair?

“It was incredible,” Fahrenkopf says. “With all the money flowing into the NFL and the millions the players are making today, my first thought was ‘Well, hell, if you are a retired player, you must be in pretty good shape.’ I had no idea.”

Few people do, which is why the Rigginses and other former players are now mounting a Washington-style campaign to publicize the inequities and try to get them reversed. Last September, along with Hall of Famers Elvin Bethea, Joe DeLamielleure, and Ken Houston, the couple launched a nonprofit called Fairness for Athletes in Retirement (FAIR). They want the NFL and NFL Players’ Association to institute pension reform: to spend millions to bring the paychecks of older retirees up to the level of those leaving the game today.

It’s a big ask, and the group doesn’t have much leverage. Improvements to player benefits historically have been made through collective bargaining between the league and the union—negotiations in which former players have little say, given that the union has no fiduciary responsibility to them. But even before that, FAIR has to lobby its own constituents, a group divided and suspicious due to prior efforts that raised money and promised change without producing significant results—a group, in other words, that would be plenty skeptical of a Washington lawyer. “I feel like a politician,” Lisa-Marie says.

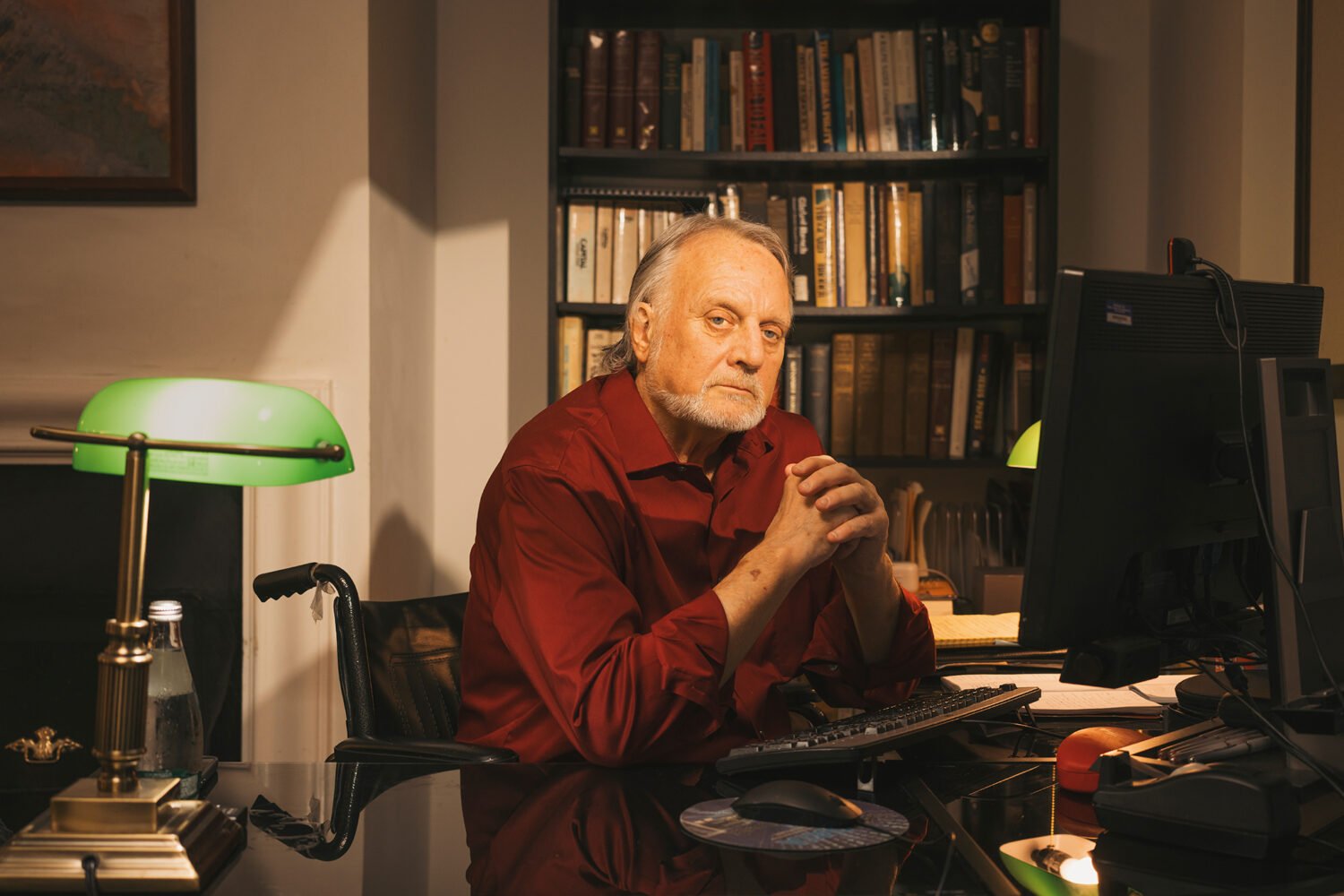

Riggo may be the name people know, but FAIR was her idea. She’s its president, the one planning donor events and working the phone. And though she’s lived in Washington for years, in some ways she’s getting her first education in the way the town runs.

Lisa-Marie didn’t know a thing about football growing up. She was a military kid who had to learn a new community every time her father, an Army Ranger, was transferred to a new post. “My dad never even watched it,” she says.

Then in 1982, she enrolled at American University, when everyone in Washington was watching the Redskins. John was the team’s most beloved star, a country boy from Kansas who became an iconoclastic folk hero—celebrated not only for powerful, punishing runs that earned him the nickname “the Diesel” but also for his off-field wit and irreverence. His “Five O’Clock Club,” in which Redskins players would gather in a shed after practice to down brews, was the stuff of legend; so was his inebriated exhortation to Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor at a 1985 black-tie dinner: “C’mon, Sandy baby. Loosen up. You’re too tight.”

John and Lisa-Marie met in the late 1980s through Riggo’s Rangers, his foundation for military and NFL veterans. He was retired by then and still a font of colorful headlines—for his unconventional side gig (he starred in a local play), his even more unconventional living arrangements (a trailer alongside the Potomac, a storage warehouse in suburban Virginia), and one big misadventure in parking (one night he found himself blocked in outside a Georgetown restaurant and used his truck to move the other guy’s truck out of the way).

Lisa-Marie was more than a decade younger and taken at first sight. They started dating a few years later, when she was living in New York. In 1992, she went along for John’s induction into the Hall of Fame. It was her first time around a large group of retired NFL players. She felt oddly at home. Like her father’s Army buddies, they were basically a bunch of grown-up fraternity brothers—never more so than when Riggo invited his former teammates to stop by the couple’s room at the Holiday Inn.

“We probably had 30 people in there, players and coaches,” Lisa-Marie says with a laugh. “It made Animal House look like piker time.” Retired defensive end Doug Atkins never left, drinking and storytelling until 6:30 am. Finally someone from the Hall of Fame knocked on the door. Mr. Riggins, it’s time for you to get in the parade car.

Four years later, John and Lisa-Marie were married in Rudy Giuliani’s office by the mayor himself. (The story in a nutshell: When the couple decided to tie the knot, they were having a late dinner in an Italian restaurant that was empty except for Giuliani and his entourage. For good luck, they later asked him to officiate, and after Hizzoner realized their faxed request on “No. 44” stationery wasn’t a prank, he agreed.)

By the mid-aughts, John was working as a football commentator and sports talk-radio host. Lisa-Marie had a new law degree from Fordham. They had two young daughters. Life was busy but good.

Then Lisa-Marie found herself walking into a Rockefeller Center cafe one day to see some old friends, Sylvia Mackey and her husband, John, a former Baltimore Colts tight end. He was wearing one of his signature black cowboy hats, Lisa-Marie says, “but he was no longer John Mackey.”

Mackey had a man purse. Inside were crayons. He had no idea where he was and wandered around the room like a young child. Sylvia broke the news: Her husband had dementia. Diagnosed a few years earlier at age 59, he had deteriorated ever since—becoming forgetful and lethargic, refusing to brush his teeth, and on one occasion being tackled by four airport security agents after he ran through a scanner checkpoint, thinking the agents were trying to steal his Super Bowl and Hall of Fame rings.

Mackey received a monthly NFL pension of $2,450. It wasn’t enough. Sylvia had gone to work as a flight attendant to help pay his medical bills. She was struggling and looking for support.

“To see what happened to them was mind-blowing to me,” Lisa-Marie says. “That’s when I started to realize there was a problem.”

At 69, Riggo has held up a lot better than many of his friends. The dark, curly hair he shaved into a Mohawk for Jets training camp in 1973 has thinned into silver wisps. But outside of a few aches and pains, his body is intact. He goes hunting and fishing in Kansas and Alaska, takes Ashtanga yoga classes, and lugs 50-pound bags of mulch around his yard.

All the same, the Rigginses themselves are not immune from money problems. After moving in 2008 back to Washington, where John had a radio show and appeared with sportscaster George Michael on Channel 4, they bought land in Cabin John and began building their dream house with Robert Gurney, the local starchitect known for his glassy, modernist mansions. Then the Great Recession hit. John’s radio contract wasn’t renewed. NBC4 canceled the show. “That was how we got our health insurance,” Lisa-Marie says. Construction on the house bogged down, and costly complications largely drained the couple’s savings. As John puts it: “It was not a great year for us.”

Super Bowl XVII. Photograph by Jerry Wachter/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images.

Super Bowl XVII. Photograph by Jerry Wachter/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images. Photograph by Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images. Photographs Courtesy of Lisa-Marie Riggins.

Photograph by Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images. Photographs Courtesy of Lisa-Marie Riggins. Riggo rushing in his famous 43-yard touchdown against the Miami Dolphins. Photograph by Tony Tomsic/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images.

Riggo rushing in his famous 43-yard touchdown against the Miami Dolphins. Photograph by Tony Tomsic/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images.Still, he and Lisa-Marie were fortunate. John landed another radio gig and later hosted a cable-TV cooking and travel show, Riggo on the Range. She passed the bar and became a prosecutor in Montgomery County at age 46.

They also had his NFL pension. Riggo’s career ended in 1985 after 14 seasons—almost four times longer than the average player’s. Today, that earns him a check of about $3,300 a month before taxes. It’s enough to stay out of the poorhouse and a good bit more than a lot of other guys his age collect.

“John has been very fortunate—he played with teammates who helped him be a Super Bowl MVP and parlay that into post-football work,” Lisa-Marie says. “But you shouldn’t have to have been at that level to be okay now.” Especially, she says, if you consider what the league distributes to younger retirees.

Under the league’s collective-bargaining agreements beginning in 1993, players who put in at least three seasons and retire right now get severance payments, life insurance, health reimbursement accounts, 401(k) plans, annuities, free health and dental insurance for five years, the option to stay on that insurance by paying premiums, and pensions starting at age 55 that pay as much as $760 a month for each season played. (In Riggo’s case, that would add up to $127,680 a year.)

But those who played at least four seasons and left the league before ’93 are entitled to just two retirement benefits: the pension, worth either $250 or $255 a month per season played, and a 2011 “legacy benefit” of an additional $124 or $108 monthly. For the average career, that adds up to $17,424 annually—just above the federal poverty level for a family of two.

Compounding the gap: Players in Riggo’s day got paid a lot less than today’s $2.1 million-a-year average. “We had to fight for every dime,” says Bethea, the FAIR cofounder, who was a Houston Oiler from 1968 to 1983. As a rookie, Bethea started every game. He made $15,000. “I did so well,” he says, “that the next year I got a raise of $1,000.”

After retiring, Bethea had surgery on his neck, then his back, and later had a knee replacement. An executive for Anheuser-Busch, he had good health coverage. Other older players were unable to land decent post-NFL jobs or lost them due to the long-term effects of the game. Chronic pain stemming from 24 knee surgeries forced Cincinnati Bengal Reggie Williams to leave a plum position as a Disney executive and pay hundreds of thousands of dollars out of pocket for medical bills and related expenses. Insurers aren’t exactly eager to offer affordable coverage to men whose football careers essentially qualify as a preexisting condition.

Bob Stein, an attorney in Minnesota who played for the Kansas City Chiefs and is now FAIR’s vice president, thinks of it this way: “If the NFL is a family, it’s sort of like the parents spoiled the younger kids and dropped the older ones off at the orphanage.”

Lisa-Marie found herself obsessing over the disparity every time a new health problem beset someone the Rigginses knew. Brad Dusek, who played for the Redskins from 1974 to 1981, recently was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). John says that two other teammates—“good friends”—endured a lower-leg and partial foot amputation, respectively. The couple would hear about “families where wives have to get jobs just for the health insurance, or adult children have to move home to take care of [their fathers],” Lisa-Marie says. “It touched my sense of right and wrong. But I felt helpless.”

As a lawyer, though—and a resident of Washington—she was better positioned than some other players’ wives to find a way she could help. In late 2015, Lisa-Marie was on a flight home from California when she got to talking football with her seatmate, a Washington lobbyist named Blair Watters. Watters had grown up rooting for the San Diego Chargers and, until Lisa-Marie explained it, had no idea about the pay gap in pensions. “How could you work so hard and be famous and then have the rug pulled out from under you?” she says.

“Adult children have to move home to take care of their fathers. It touched my sense of right and wrong.”

Watters suggested going to Congress—why not try to leverage the lawmakers in the Rigginses’ own back yard? Lisa-Marie was intrigued. But what should she ask Congress for?

The NFL offers aid to retirees with health problems, including disability coverage. But players have long complained that the programs are maddeningly inaccessible, too often resulting in denials and legal fights. Similarly, recent settlements of class-action lawsuits over both concussions and the use of retirees’ images created multimillion-dollar benefit funds that players have had a hard time accessing. Lisa-Marie wanted to avoid asking for anything that would create new hassles. Pension parity, on the other hand, would be a frictionless transaction—and seemed simple enough to explain to a busy member of Congress.

Then she had her lunch with Fahrenkopf. “I’ve been on the Hill,” the former RNC chair says. “A lot of members are my friends. You can go in and sit down with a senator and they’ll listen to you and shake their head yes and all that stuff. Then the next person comes in to tell their story.”

He laughs. “And then you go home and end up getting a fundraising letter!”

Fahrenkopf suggested a different approach: Treat the pre-’93ers like a candidate for office and essentially run a campaign. Educate and rally the fans. Apply public pressure. Don’t confront—persuade. That appealed to Lisa-Marie. She remembered rolling her eyes at shouty, finger-jabbing defense attorneys when she was a prosecutor. “I don’t like being a bully,” she says. “And people don’t listen when the volume is turned up. They tune you out.”

Rallying ex-Redskins Mike Bragg to her cause during a player reunion in December. Photograph by Jeff Elkins.

Rallying ex-Redskins Mike Bragg to her cause during a player reunion in December. Photograph by Jeff Elkins. Lisa-Marie and ex-Redskins player Mark Moseley pose for a picture. Photograph by Jeff Elkins.

Lisa-Marie and ex-Redskins player Mark Moseley pose for a picture. Photograph by Jeff Elkins. Riggins and Billy Kilmer, another ex-Redskins. Photograph by Jeff Elkins.

Riggins and Billy Kilmer, another ex-Redskins. Photograph by Jeff Elkins. She met with a series of familiar DC types—lawyers, lobbyists, journalists, political strategists—one introduction leading to the next. Eventually, she connected with Danny Diaz, a media-savvy Republican operative (he managed Jeb Bush’s presidential campaign) and a Riggins-era Redskins fan who offered his help pro bono. Now Diaz’s firm is building FAIR’s PR campaign, pushing out emotional video testimonials from former players and trying to seed the cause in social-media feeds.

“People met with me solely because of my last name and the currency it has in this town,” Lisa-Marie says. “There’s no way I could have done this living in Arkansas.”

Which isn’t to say it hasn’t been complicated. Even a grassroots campaign these days needs money—for legal fees, accounting, website hosting. She’s already learned the first lesson of politics: Candidates have to dial for every dollar. It’s the only part of the campaign that makes her uncomfortable.

Last June, FAIR held its first fundraiser. One time Redskins quarterback Billy Kilmer was there. So were a handful of former players’ wives. Roy Kapani, an entrepreneur and Riggins family friend, spoke about how his parents had immigrated to the United States from India and how his ethnicity had sometimes made him feel out of place. He described taping a Band-Aid across his nose—to copy Kilmer, his favorite player. Football, he said, had been his bridge to belonging. Now he felt compelled to help. He announced that he’d match up to $100,000 in donations. “The wives had tears in their eyes,” Lisa-Marie says.

THE HIGH WORE OFF PRETTY QUICKLY. It turns out that the politics within the world of NFL retirees are fraught. Like any political movement, FAIR needs a unified base—and former players are anything but.

Around the time FAIR went public, the football world was caught up in a controversy over a letter from a group of Hall of Famers led by former Los Angeles Ram Eric Dickerson. They were demanding that they get money and insurance exclusively for themselves or they’d boycott future Hall of Fame ceremonies. Although Dickerson later said the group wanted better benefits for all retirees, it looked like a self-serving money grab by stars and quickly prompted a backlash.

Retirees who played an average of four years and quit before 1993 collect an annual pension of $17,424, or just above the federal poverty level for a family of two.

There’s a long history that prompts retired players who don’t work for the NFL or the players’ union directly—or within the football-industrial complex of broadcasting and coaching—to question the motivations of those who do: Are they ultimately loyal to their peers or to their paychecks?

In 2007, Hall of Famer Mike Ditka—an outspoken critic of the treatment of older retirees—came under fire after it was revealed that a charity he’d created for needy former players had collected $1.3 million over three years but netted only about $315,000 after expenses and distributed just $57,000 to retirees.

All of this makes it tricky for a retired gridiron legend and his Washington-lawyer wife to assemble a coalition. After FAIR’s website went live, Lisa-Marie was caught off-guard by suspicious chatter: Two relatives of former players used a private Facebook page frequented by football families to question whether the organization was simply exploiting retirees for money.

When she saw those comments, Lisa-Marie was in a hotel room in Cleveland preparing for a trial in Maryland the next day. John was across the street at the Cleveland Clinic getting a comprehensive physical. “I was shocked and horrified,” she says. “I had no idea how deep the feelings of betrayal among these families went.” She spent the next two hours on the phone with the wife of a retiree who had a relationship with both of the relatives, pressing her case. The wife passed on the message, putting out the fire.

Jane Arnett, the wife of former Rams star Jon Arnett, spent much of the aughts advocating for former players—her behind-the-scenes efforts helped create the monthly “legacy benefit” in 2011. Now she’s advising Lisa-Marie. “These are proud men, whose character is to handle every challenge and win, power through no matter what, don’t cry, and get the job done,” Arnett says. “There’s a lot of shame when they don’t have food in the kitchen or can’t keep the utilities on. That’s one of the reasons nothing was done in the past—they weren’t complaining.”

Tom Mack, an adviser to FAIR, is one of the retirees who have tried to do something, previously lobbying the league for pre-’93 pension improvements. A brainy former offensive lineman who worked as an engineer during his off-seasons—and once crafted his own three-page proposal and accompanying chart while negotiating deferred payments from the Rams—Mack calculates that parity would cost roughly $1.2 billion over six years, or $6.6 million annually for each of the league’s 32 franchises. That’s not cheap. But that yearly cost is also less than 2 percent of the NFL’s annual revenue, and it’s not a permanent cost—more of a mortgage to pay down as older guys pass away.

Like any political movement, Fair needs a unified base – and former football players are anything but.

But will the league and the players’ union be swayed? Their current labor deal will expire in 2021, and negotiations for a new deal likely will begin before then. Last fall, Lisa-Marie spoke to two league insiders who told her that team owners are sympathetic. But they also said the only way a boost will happen is if the union—whose leader has spoken out in favor of retirees but isn’t legally obligated to represent their financial interests—makes it a priority. So FAIR now has to game out how hard to lobby either side behind the scenes and muster as much influence as it can through the court of public opinion. With the NFL coming off snafus and controversies ranging from Deflategate to its handling of domestic violence, owners and players may be eager to generate positive headlines. But maybe only if FAIR’s cause goes viral.

“I’ve been on both sides of that table,” says Stein, the FAIR vice president, who was a union player rep when he played for the Kansas City Chiefs and later was CEO of the NBA’s Minnesota Timberwolves. “I don’t think the owners or the players are bad guys. But here’s the problem: Every dollar they allocate to retired players is a dollar that doesn’t go to them.”

Last fall, John and Lisa-Marie’s elder daughter, Hannah, came home from college on Columbus Day weekend to visit her parents. But on the actual holiday, she hardly saw her mother. Lisa-Marie was holed up in her home office writing to potential donors, hosting a conference call with retirees’ wives, crafting FAIR board-member bios for the organization’s website. She came downstairs only to have dinner.

“We all teased her: ‘Are you sure you don’t have another call to make?’ ” Hannah says. (She did, but she put it off till after the meal.) “Sometimes she’ll be running late and you wonder what’s happening,” Hannah adds. “Then you go out to the garage to get something and she’s still sitting in her car talking on the phone.”

Relatives of former players used Facebook to question whether Riggins’s organization was exploiting retirees for money.

From her desk, topped with folders and legal pads, Lisa-Marie can see John cooking in the kitchen and their younger daughter, Coco, watching TV in the living room. When she had the idea for FAIR, she cut back on her caseload at her Rockville law firm. She told the managing partner she hoped she could get the nonprofit off the ground in six months. That was almost three years ago, and she’s still sacrificing billable hours. She feels guilty for ignoring her family when she’s working on FAIR—and guilty for ignoring FAIR when she’s not.

During law school, she read the Charles Dickens novel Bleak House. One of the characters, Mrs. Jellyby, has devoted her life to setting up a mission in Africa, all while ignoring the needy right around her. “I get scared that I am becoming that person,” Lisa-Marie says. “I don’t make money at this. I’m obsessed. Sometimes I go to bed and think, ‘What the heck is my deal?’ ” But she’s raised more than $100,000 for the campaign so far, and she can’t stop now.

John, the self-proclaimed “camp cook” and “pool boy” of the Riggins household, insists he isn’t worried. “As long as the power is still coming into the house, it’s not an issue,” he says with a wry smile. “If that [stops], we may have to revisit this.”

Way back when, John was known for a willingness—an eagerness, some would say—to buck football’s authoritarian culture in ways both puckish and daring, such as the time he held out for an entire season over a contract dispute, then returned to the Redskins with a blunt proclamation: “I’m bored, I’m broke, and I’m back.”

But with FAIR, “the Diesel” is more than happy to let Lisa-Marie do the running. “She’s the embodiment of the right person to be doing what needs to be done,” he says. “All I can do is sit back and applaud.”

This article appears in the February 2019 issue of Washingtonian.