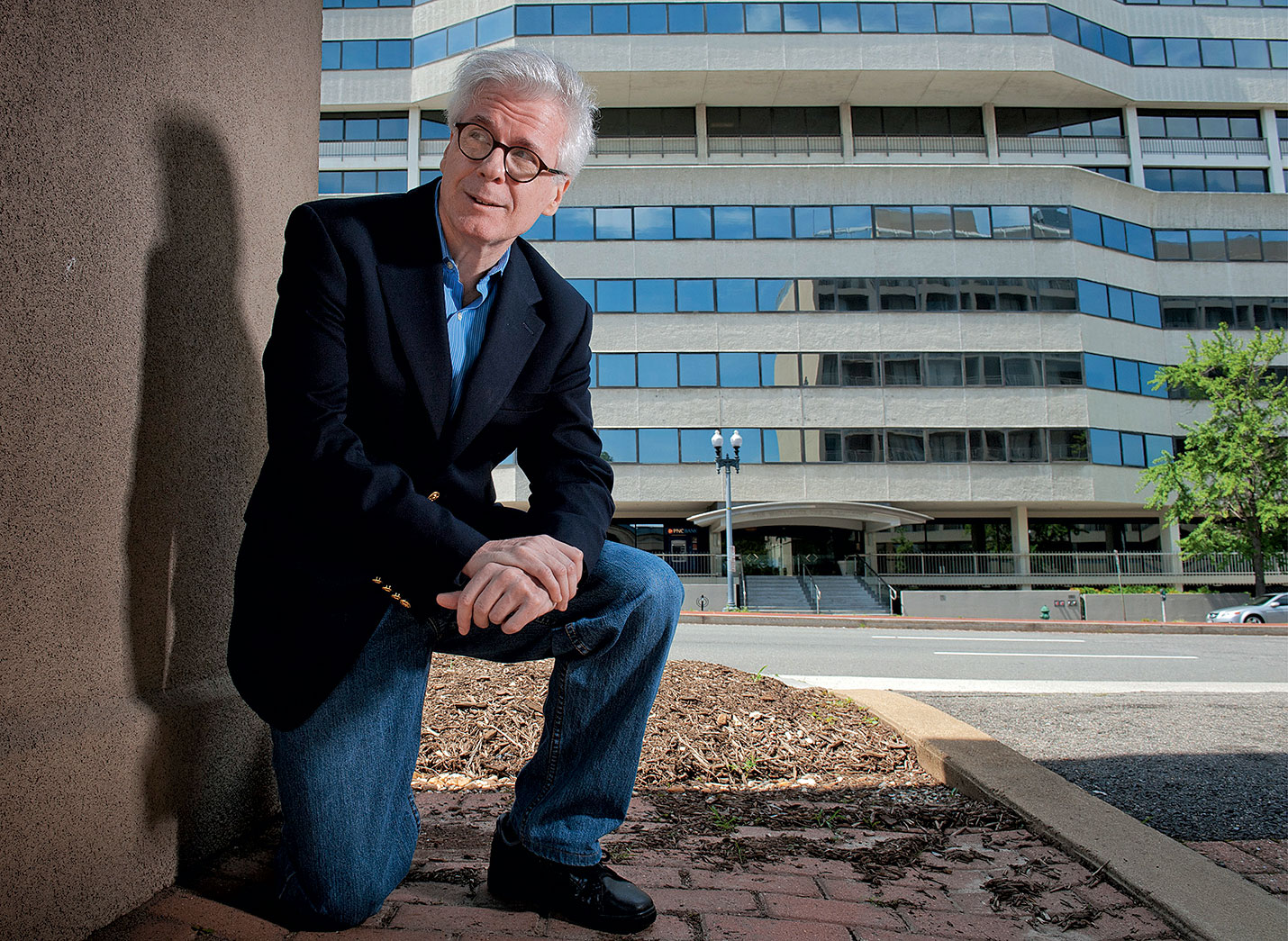

DC novelist Thomas Mallon has a knack for rendering convincing fictional portraits of American Presidents. After books about Ronald Reagan (Finale) and Richard Nixon (Watergate), he’s now back with Landfall (out Feb. 19), a look at George W. Bush’s presidency that focuses on the period around Hurricane Katrina.

What made you want to write a novel about George W. Bush?

The Watergate novel came out in 2012, and then I did Reagan. I was talking with my longtime editor, Dan Frank, about what was next. I remember Dan asking me about Bill Clinton. Clinton was interesting, and I thought he was a complicated person; there was no mystery about Bill Clinton—the components were evident. Obama is more mysterious, harder to grasp, but I didn’t really think it was my subject, my story. GWB interested me a lot. I worked in the administration [as deputy chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities] for the years that I’m writing about, ’05 and ’06. I wanted to chronicle this very turbulent time, the [years around] Katrina and the Iraq insurgency, probably the hardest years of Bush’s presidency.

I had a definite sense of Bush’s admirable motives, but even he would admit that things hardly went according to plan. And I wanted to write about him. I was interested in his personality. I was struck by what I would characterize as these rapid alternations between the comfortable-in-his-skin good old boy—the witty, joking guy—and the other side of Bush who could be very short with people. You could see everything in George Bush on his face. That was something that I also wanted to explore.

In some ways, Bush’s role in the book is as much as a matchmaker as a policymaker.

In a way. He does take this interest in [the book’s two central fictional characters], partly because I do think he’s a very personal, emotional person. The whole Bush family is very emotional in a lot of ways. Certainly his father was. A lot of tears. So I think it was plausible, emotionally, that he would get involved. This must be an inclination that Presidents experience from time to time when things are seeming intractable. There must be a kind of pleasure in dealing with very small things, where suddenly you can feel efficacious again when everything seems to be kind of impossible on the macro level. The failures [chronicled] in the book . . . I think the hurricane essentially ended his presidency. Politically, all the juice was gone after the fall of 2005.

The title, Landfall, obviously refers to Hurricane Katrina, but the book is also about the fallen land of Iraq. Why did you want to re-litigate issues around the Iraq war?

When you say “re-litigate,” I know what you mean, because in effect the book does do that. It presents people in arguments all the time over Iraq. But in a sense I’m trying to show the way in which once they were there, almost nothing was able to resolve itself. What I wanted to show, more than anything else, was the frustration, the conundrum, that Iraq was.

One of the things that all three of these novels have is they show the degree to which people’s personal feelings about themselves and other people have an impact on the political actions that they take. You see many people who are trying to do things that they believe, but they’re imprisoned by their personalities, their own psychological compulsions, agenda, whatever it is. I do think that’s to a great degree how history gets made. A lot of it is very personal and accidental.

What would Bush think of Landfall if he read it?

He’d probably curl his lip a little bit. Maybe there would be parts that would amuse him. I think there would be parts that he would say showed me to be completely off base. But, you know, it’s a novel. I think the portrait of him in the book is affectionate, and sympathetic to the extent that it’s trying to show the frustrations and difficulties of those two years. You can’t write a novel wearing kid gloves.

You conspicuously mention Donald Trump at the end of Landfall. Is that a hint that you’re now working on a Trump novel?

It’s flagrantly not the case. I’m so happy to tell you that it’s not the case. There’s no inner life with Trump. There’s no moral complexity, no ability to feel any guilt or any ambivalence. As a result, I don’t think he’s a morally interesting man, because I don’t think he operates with the normal levels of moral hesitation, moral reevaluation of things. Even if I could find a way to write about him as a character, I wouldn’t write a novel about this time, for the sheer distastefulness of it. My only goal is to survive this presidency—not to chronicle it.

This interview has been edited and condensed. A version of it appears in the February 2019 issue of Washingtonian.