Last year, a major internet concern chose Washington as the location for a second headquarters. We’re speaking, of course, about the influential tech journalist Kara Swisher, who recently started splitting her time between Silicon Valley and a second home in Shaw.

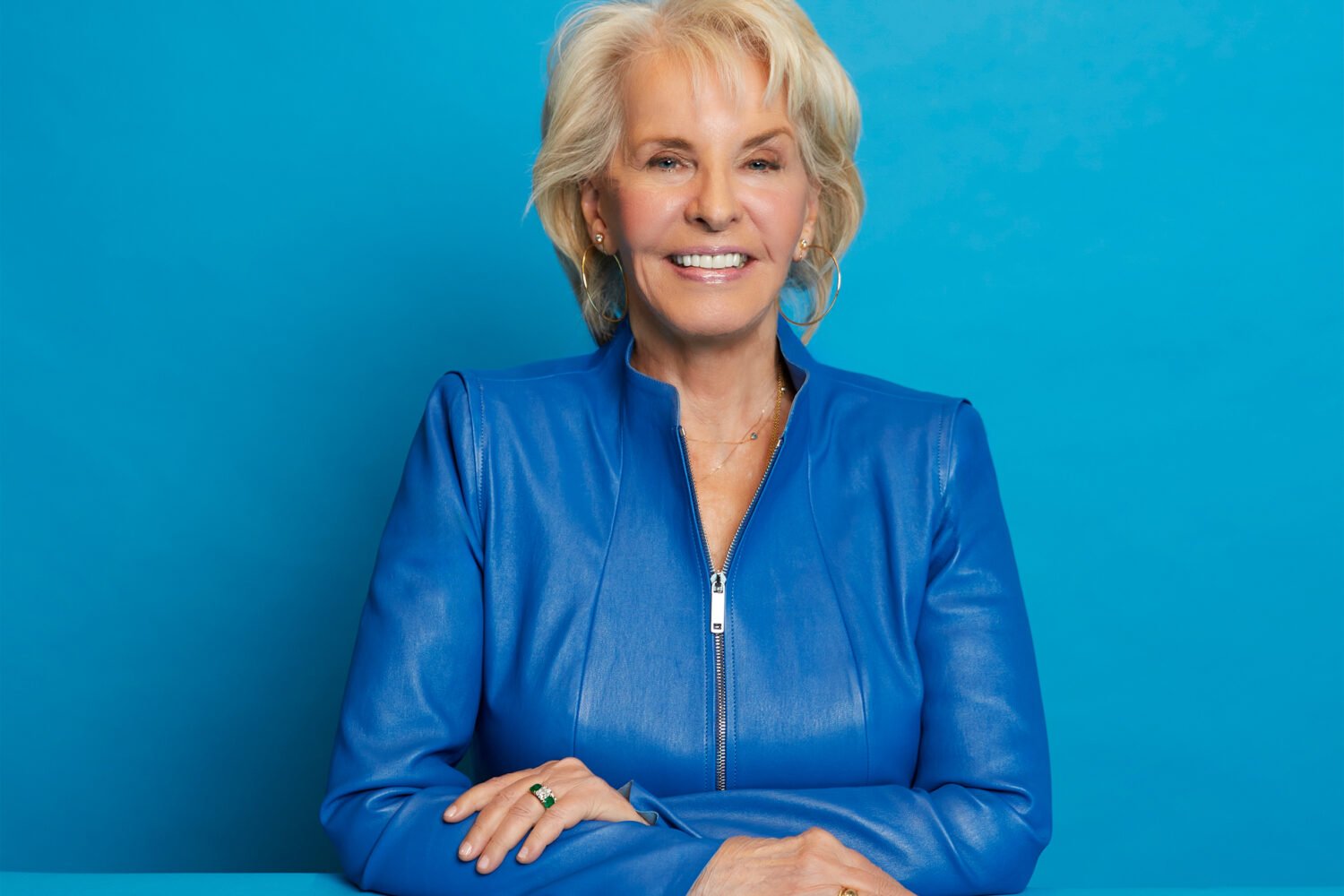

Swisher, who rose to prominence covering tech for the Wall Street Journal, is as well known in Silicon Valley as Mike Allen is inside the Beltway. She’s executive editor of the must-read industry news site Recode; host of a podcast series, Recode Decode; co–executive producer of Recode’s conference business; a commentator on MSNBC and NBC; and a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times.

DC’s not an exotic locale for Swisher, a Georgetown University alum who did stints at the Washington Post—where she covered a nascent company called AOL—and Washington City Paper, from which she somewhat famously got fired (“I was unqualified anyway,” she says).

Swisher somehow found time to meet us at the Dupont headquarters of Recode’s parent company, Vox Media. As we chatted, she removed her trademark sunglasses, ate a salad, and—because she seems to never quite stop working—periodically broke to take calls and check the news.

What don’t people in Washington understand about the tech world?

Everything. There are people in government who are very up to speed on what’s happening and who have a good sense of what’s occurring and what needs to be done. It’s just that Europe and the states like California are way ahead of the federal government on [regulating the tech business]. And now you throw in Trump with his crazy accusations against tech. But you know, he does have a sort of lizard sense that tech is too powerful. That’s probably the only thing he’s marginally correct on, that there has to be some sort of regulation, even though tech seems to have benefited him quite a bit.

The inverse question: What does Silicon Valley get wrong about Washington?

That it doesn’t matter. [There used to be this] ignorance—acting like they didn’t need to be here. Of course, now they’re here in full force. I can’t walk anywhere without running into a tech lobbyist.

It’s not just lobbyists. Amazon is about to dump a bunch of new people into this area.

[Jeff Bezos] is very savvy. I mean, you can say his buying the Washington Post was an attempt to influence legislation. But I don’t know, I think it just interested him.

What’s the first thing that the social-media companies should do to fix their platforms?

Their basic architecture suggests chaos, so I’m not sure. They built these things without any concept of how big they could get or how much damage they could do. I was there. They were thinking of growth, growth, growth. So after the [2016] election, when it was clear there was some abuse of platforms . . . . A line I use a lot is that the Russians didn’t hack Facebook, they used it as a customer. Now we’ll never know the impact. I don’t know who’s capable of fixing it, but it’s certainly not this group of [tech leaders].

What about Twitter?

You have a point of view, an editorial point of view. They want to have no point of view. [Twitter CEO] Jack Dorsey wants to create a platform that just is what it is. It’s like building a city in which there is no police, no fire, no garbage men, no sewer, no signs. And they collect the rent.

It’s like Escape From New York.

Exactly. With the New Zealand massacre, [the platforms] removed, what, 1.5 million videos? There were still hundreds of thousands up. They cleaned up most of it, but there’s still that toxic waste that’s sitting there.

Is it that they don’t think values scale?

I don’t think that they are evil people. I think they’re ignorant, and I think they’re naive.

Mark Zuckerberg always ends up saying something to me that’s not good for him.

Elizabeth Warren wants to break up Facebook. What do you think government should do?

I don’t agree with a lot of her things, but I like that the discussion’s going on. Should Facebook own all these communications platforms? In the US, and in a lot of the world, they’re the de facto way people get their news. Amazon’s in a more interesting situation because they’re a small part of retail overall but they certainly dominate online commerce, and they certainly are poised to dominate all of it. Then there’s the question of data privacy—and the addiction that goes with it, too. It’s just on and on and on.

What you’re describing is basically an enormous Gordian knot. Can these problems actually be solved?

It’s a free-for-all, but the people who made it have gotten obscenely wealthy. So they benefited, they made a mess, and they’ve taken a lot less of the responsibility than you’d imagine they should. People compare them to cigarette makers, but I think it’s more like chemical manufacturers. In general, we have certain strictures on chemical companies and we don’t have any on internet companies. Is that any different? Is spewing all that violence and hate toxic? Someone’s got to decide this. Not me, but someone has to.

Somebody in government?

I don’t know. Somebody. But [the tech companies] are making all the money from it, right? So it’s a tax on the rest of us. The question is: What are their responsibilities as media companies? And they are media companies. If anybody could get on a TV network and do anything they want, everyone would think that was crazy, right? There are rules around the uses of TV networks. Why can’t they do the same thing [for the internet]?

When did these companies and tech CEOs stop being lovable and cute to us?

They were always not lovable and cute to me. You could see their aggression. The issue is: What kind of internet do we want, and who decides that? Since it was started as a public trust, why did it suddenly get captured by commercial interests that take every bit of value out of it and pay none of the costs?

You run a media business, appear on television, do a regular podcast, and write for the New York Times. Plus you live in two cities. How do you get any-thing done?

I have too many jobs. I am a creative person who’s also restless. Really early on, when I was an employee of the Washington Post and after that an employee of the Wall Street Journal, I realized I’m a terrible employee. I don’t like listening to people. So I try to put myself in a position where I can do a lot of ideas.

How much time do you give to preparing for your podcast interviews?

None. I know, I should say hours.

How are you able to go in there and al-ways sound like you know what you’re talking about?

I’ve been covering tech for 25 years. I do know what I’m talking about. I think if you prepare too much for these things, you don’t have really good conversations. That’s the other thing: People say things to me. I don’t know why.

Maybe they’re scared of you.

No! Like, Mark Zuckerberg always ends up saying something to me that’s not good for him.

I don’t know why he keeps letting you interview him.

I don’t think it’s going to happen again. Maybe one more time. Maybe he goes [exaggerated villain voice], “This time I’m going to get her!” He’s a very sweet man. In many ways, he’s one of the nicer, more polite billionaires out there. He is, in fact, lovely, and he tries really hard. It’s just he’s not succeeding.

We’ve talked a lot about the negative aspects of tech. Are there good lessons to learn, like the way you can build your own career? You’ve certainly done that.

Yeah! Entrepreneurism is the most important thing to get our country to the right way we want it. We want people to be entrepreneurial. And there’s a lot of things you can learn from Silicon Valley in that genre. The idea of quickness, efficiency, innovation, entrepreneurship. There’s great advances in medicine and things like that.

But tech has really changed the way we live in every way. You don’t want to be the person on the beach at Kitty Hawk, when they take off in an airplane, going, “It only went two feet.” They flew! What a miracle.

This article appears in the May 2019 issue of Washingtonian.