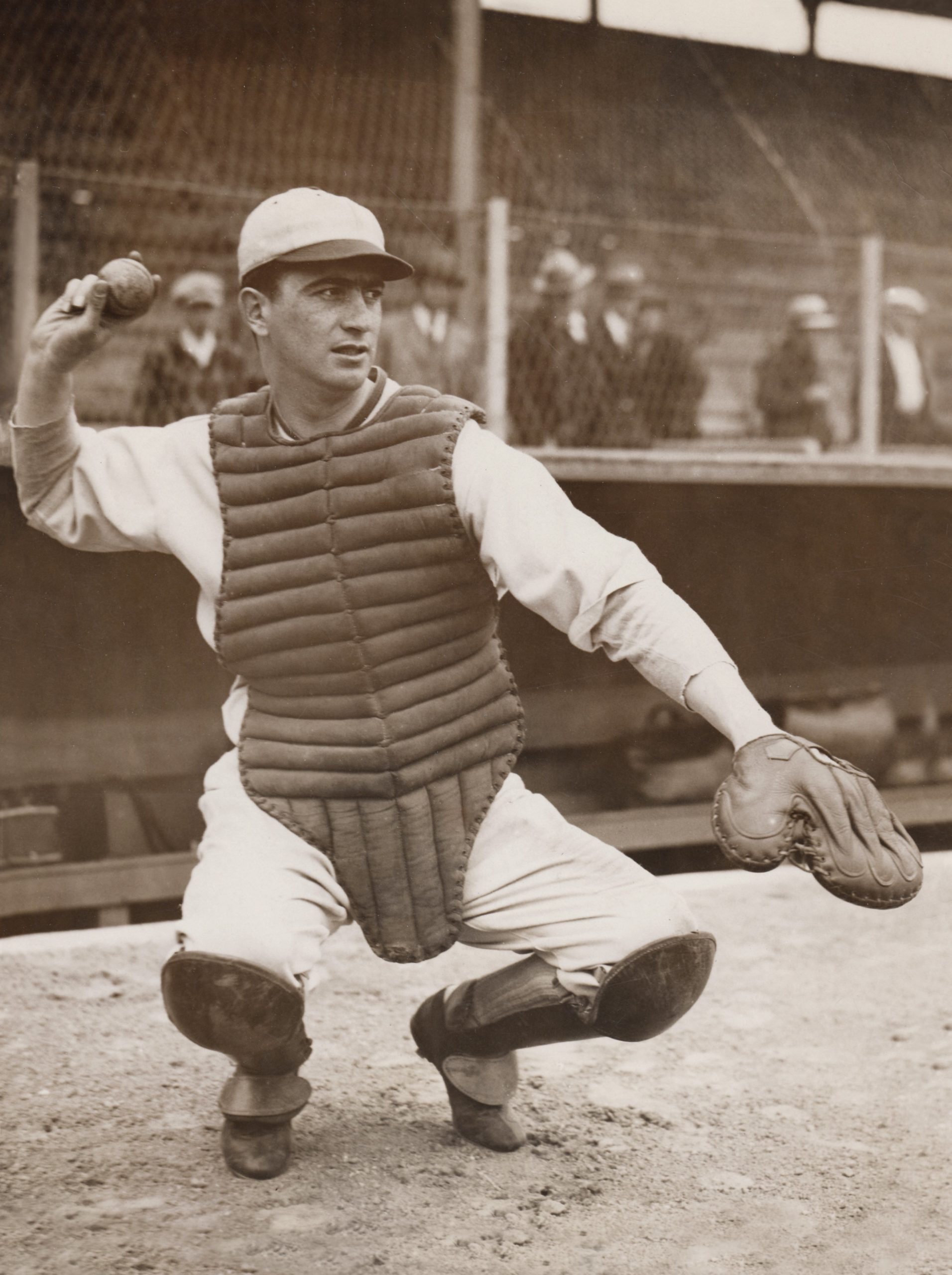

During 148 games between 1932 and 1934, Moe Berg played catcher for the Washington Senators. He was also a talented spy for the US government. In a new documentary, The Spy Behind Home Plate, director Aviva Kempner traces Berg’s departure from baseball in 1942 and follows him into the ranks of the OSS, the precursor to the modern CIA, during World War II. His work took the form of espionage missions to Zurich and Italy, providing key intelligence to leaders of the Manhattan Project. Berg’s assignments, which involved assessing top European physicists, reflected the deep anxieties within the OSS about the Nazi capability to develop a nuclear weapon. As Kempner describes, “The kind of research Moe did was able to put the nail in the coffin of what the Germans knew.”

It’s not hard to imagine how the catcher first attracted the attention of intelligence officials; Berg was not a typical ballplayer. He earned degrees in linguistics at Princeton and law at Columbia, and his reputation in the ballpark, which was modest, was dwarfed by his fame on popular radio, where he frequently competed on quiz shows. He was said to keep a tuxedo in his locker. In a Buttiegieg-esque detail that rankled his teammates, Berg was known to speak seven languages. (“Yeah,” said Senators outfielder Dave Harris, “and he can’t hit in any of them.”)

The documentary plumbs a few mysteries, too. The most persistent involves when, exactly, Berg began his clandestine work. The Spy Behind Home Plate suggests he might have been recruited as early as his time with the Senators. In 1934, during Berg’s last season in Washington, a delegation of American all-stars was selected to play in Japan. With little explanation, and despite suffering an anemic batting average of .185, Berg was plucked from obscurity and added to the trip. He returned with his travel bag stuffed with rare camera footage of downtown Tokyo. Whether he was a civilian or a spy, the reels nevertheless found their way into the hands of American intelligence agencies.

After the war, Berg became something of a recluse, settling in New Jersey and visiting the occasional ballpark until his death in 1972. For Kempner, who lives in Washington, the DC screening of The Spy Behind Home Plate offers a kind of homecoming for Berg. In an interview edited and condensed for clarity, Kempner spoke with Washingtonian about the documentary, which debuts May 24 at the Avalon Theater.

What first drew you to Moe Berg?

My M.O. is to do films about under-known Jewish heroes. This one combined my love of baseball and my living in Washington since 1973—especially since he played for the Senators. I just was thrilled to be able to combine those, and also draw a character who both with his brawn and his wits was able to spy. I also seem to have a propensity for films with “Bergs” in the title—Hank Greenberg, Molly Greenberg, and now Moe Berg.

Going into the project, I knew less about the OSS, the precursor to the CIA. They combined both women and men, and Ivy League and safecracker, people who fought in Spain, children of immigrants who knew languages, and did some incredible spying to be able to help the Allied effort.

But the biggest issue looming over us is nuclear weapons. Senator [Edward] Markey is in the film, and he was with me [this week] at the screening, who pointed out we would not be here today if Hitler had people who could create the atom bomb. And today we have to worry about North Korea, we have to worry about the Middle East, maybe Russia. This issue of nuclear [weapons] still looms very much over here.

What kind of character was Berg?

He probably was the brainiest man who ever played baseball—a total linguist. He may have spoken up to ten languages. From an early age, to be able to play on a Christian team, he changed his name, [using] less-ethnic pseudonym Runt Wolfe. Being the child of immigrants, he knew languages, he traveled every winter. He knew what was happening in Europe, loved reading newspapers. He [frequently asked] his fellow players whether Mussolini would prevail or not. Just very well informed.

How did Berg fall into spying?

Well, it’s a little up in the air. Japan in ’34, Berg went to play on the all-star team, and he secretly took footage of the skyline of Tokyo that might have been used to help the Doolittle raid. I never found out if in fact he was a spy [at that point], but I think he has all the makings of doing it.

After baseball, he did some work for Nelson Rockefeller in Latin America to see if there was any German influence. For OSS, he would have trained here. All OSS people trained in the Washington area—people like Marlene Dietrich, Julia Child, Arthur Goldberg, Arthur Schlesinger, Ralph Bunch, and William Colby.

He was specially chosen to do nuclear espionage. At the time, we were really worried. The Manhattan Project was going on, and FDR hadn’t even told Truman. And Berg came back with essential information that really allowed us to continue with the Manhattan Project. Moe was essentially the nuclear spy.

His life after the OSS is also somewhat of a mystery. You think there’s evidence his spying continued?

Yes. There was some talk he did some work for Golda Meir, but we could never find out exactly what it was. And then there as some work he did after [after the war], in terms of getting scientists away from the clutches of the Soviet Union.

He settled in Newark. When anyone would ask him what he did, he would put a finger to his mouth. I think it was hard to adjust back to normal life. He didn’t want to practice law—he went to law school to satisfy his father, who never saw one game when he was young, or the 15 years in the major leagues. But he never lost his love of baseball.

Will Washingtonians recognize any landmarks in the film?

Yes. Moe was a very important player here, when the Senators were in the World Series. He also attended embassy parties, where he got his chops not only being charming but also trying to figure out what other countries were up to during [the war]. Certainly he got his OSS training here, got his OSS orders here. The Congressional Country Club was once a training place for the OSS, and I believe Camp David was. He liked to frequent the Mayflower.

Ian Fleming of 007 fame came [to Washington] and helped Bill Donovan. They worked in the house that later Katharine Graham owned. Wild Bill Donovan owned that house. You can’t make it up.

Was the film any more rewarding because you’re a Nationals fan?

Actually, I’m going to be at [Nats] stadium Friday night to show excerpts of the film. I have Walter Johnson in the film. He was the greatest pitcher of his era—he would pitch the whole game, no one was like him. We’re hoping to celebrate that fact in spite of the team today. Right now, our pitching is killing us.